November 4, 2016, by Charlotte Anscombe

Guy Fawkes night: celebrating the most famous act of counter-terrorism in history

Dr Louise Kettle from the School of Politics and International Relations writes for The Conversation about one of the most famous terrorists of all time…

‘With the terrorism threat level remaining at “severe” (meaning an attack is highly likely), and the head of MI5, Andrew Parker, warning that “there will be terrorist attacks” in Britain, there is a climate of continuous public concern.

And yet this November 5, like every other, the British skyline will be filled with explosions and the public will look on in delight. The story behind this annual celebration can become muddled, but it’s worth remembering that Guy Fawkes night marks the most famous counter-terrorism mission in history. Counter-terrorism is going on around us at all time – we just aren’t usually allowed to know about it.

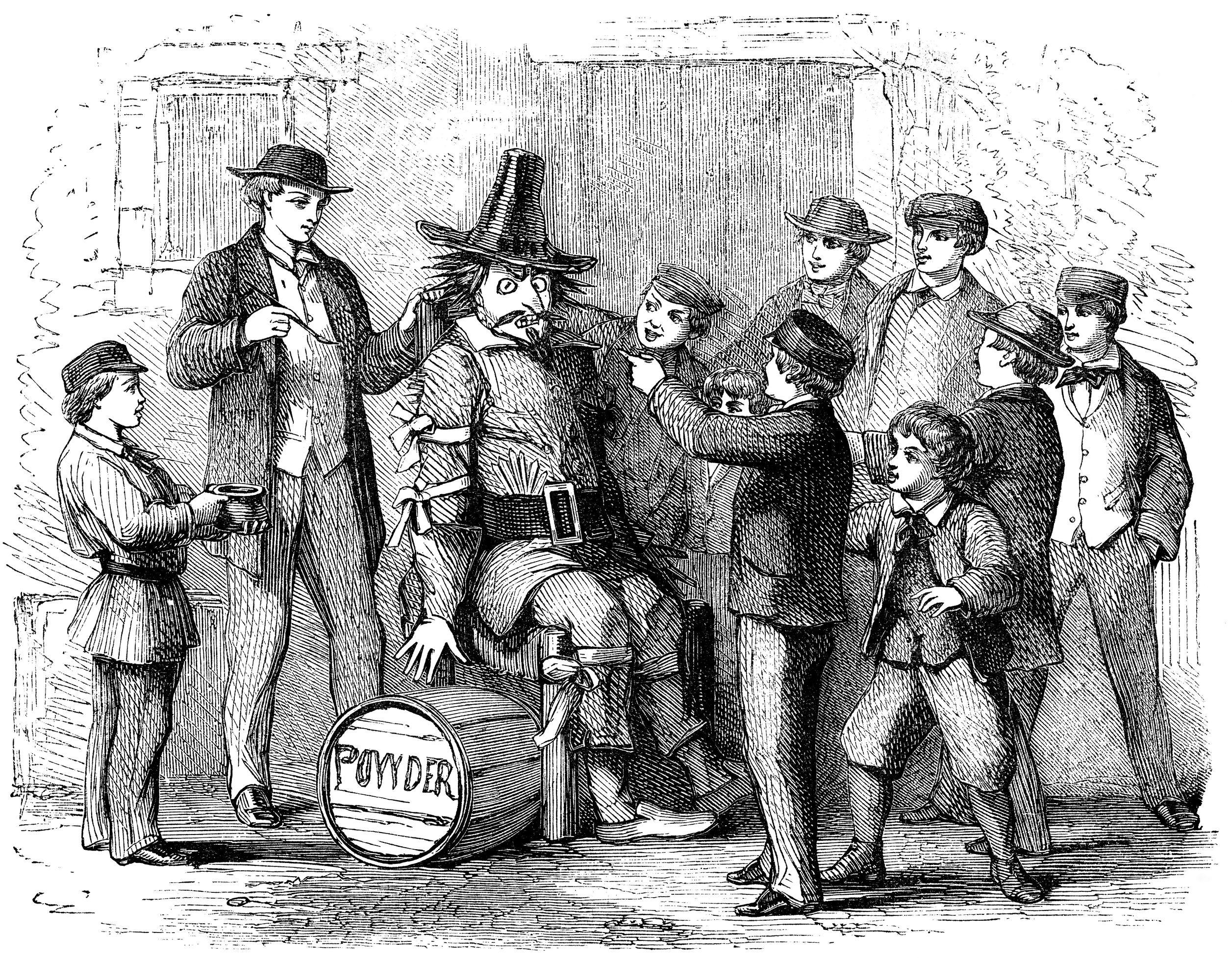

Many, if not most, of the families attending fireworks displays on this weekend will know the story of Guido “Guy” Fawkes. Fawkes, along with his 12 co-conspirators, tried to assassinate King James I of England and IV of Scotland by blowing up the Houses of Parliament with 36 barrels of gun powder. This was a planned act of terrorism to take place at the opening of Parliament on November 5 1605.

Religious motivations

Similar to a number of terrorist groups today, the plotters were driven by religious motivations. Under Protestant Queen Elizabeth I, many Catholics had suffered religious persecution. King James was also Protestant but his mother – Mary Queen of Scots – had been Catholic, leaving many hopeful that he would be a more religiously tolerant monarch.

Upon his coronation in 1603 King James failed to reverse the anti-Catholic laws. Instead he began to order Catholic priests to leave the country and increased oppression further by introducing legislation which refused Catholics the right to receive rent or make wills.

In response, Robert Catesby, an English Catholic and the leader of the gunpowder plot, started to plan King James’ assassination. He thought that killing the King would incite a popular revolt whereby the throne would be returned to a Catholic – James’ daughter Princess Elizabeth.

Catesby began to assemble a group of like-minded individuals who had the will and expertise to carry out his ideas. Guy Fawkes was recruited in April 1604 by Catesby’s cousin, Thomas Wintour, in Flanders. He was enlisted for his specific skill set – he was an explosives expert who had been fighting for the Spanish army.

Successful counter-terrorism

After a few changes of plan, one of the plotters, Thomas Percy, rented a vault under the House of Lords, where the gunpowder was stored. But the opening of Parliament was delayed a number of times – largely due to fear of the plague – leading to a need for further funds. As a result, additional wealthy individuals were recruited, including Catesby’s cousin Francis Tresham.

On October 26, Tresham’s brother-in-law, Lord Monteagle, received an anonymous letter warning him not to attend the opening of Parliament. The letter was passed to the King and the authorities searched the cellars of the Palace of Westminster. The gunpowder was discovered and the plot foiled.

Guy Fawkes, who had been given the responsibility of managing the explosives and lighting the fatal fuse, was found in the early hours of November 5 1605. He was captured, questioned and eventually tortured to extract a confession. The other plotters were summarily rounded up, killed or arrested and later hung, drawn and quartered.

Marking the day

The year after the failed plot, Londoners were encouraged to light bonfires to commemorate King James’ survival. This tradition continues each year with Guy Fawkes – Britain’s most famous terrorist – annually punished through effigies (“Guys”) that are burnt on the top of bonfires.

The noise and spectacle of bonfire (or fireworks) night serves as a regular reminder of what might have been had the terrorist attack succeeded. Therefore the event is, in part, about religious terrorism and the actions of a terrorist group.

But the fires actually represent the blaze that never was. Similarly, the fireworks and their associated bangs represent the gunpowder that did not explode. Furthermore, the “Guys” only exist because Guy Fawkes became notorious once he was caught. Consequently, the events are less about remembering terrorism and more about celebrating successful counter-terrorism.

The nature of contemporary counter-terrorism means that successful operations are rarely known, let alone celebrated. There have reportedly been 12 terror plots thwarted in the UK in the past three years but the details of these operations often remain secret within the security services.

But in an environment of concern over the threat of terrorism, it is perhaps even more important – and perhaps reassuring – to remember that the festivities this weekend recognise a long tradition of successful counter-terrorism. And that’s even more reason to join in the celebrations.’

This article was first published on The Conversation.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply