May 1, 2015, by Lindsay Brooke

How to run a general election sweepstake

Pens and paper at the ready? Here’s some advice on general election sweepstakes from Graham Kendall, Professor of Computer Science at The University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus.

Around 50% of people in Britain gamble every month, with about £150m being staked on the Grand National alone. And the Grand National is a perfect opportunity to hold a sweepstake, where everyone pays a fixed amount, draws a random horse, and the people who drew the first three or four horses collect shares of the total prize money.

It’s easy to design a Grand National sweepstake. The race has a large number of competitors, it’s not obvious who will win, outsiders have a real chance, and all in all, drawing a horse at random seems reasonably fair.

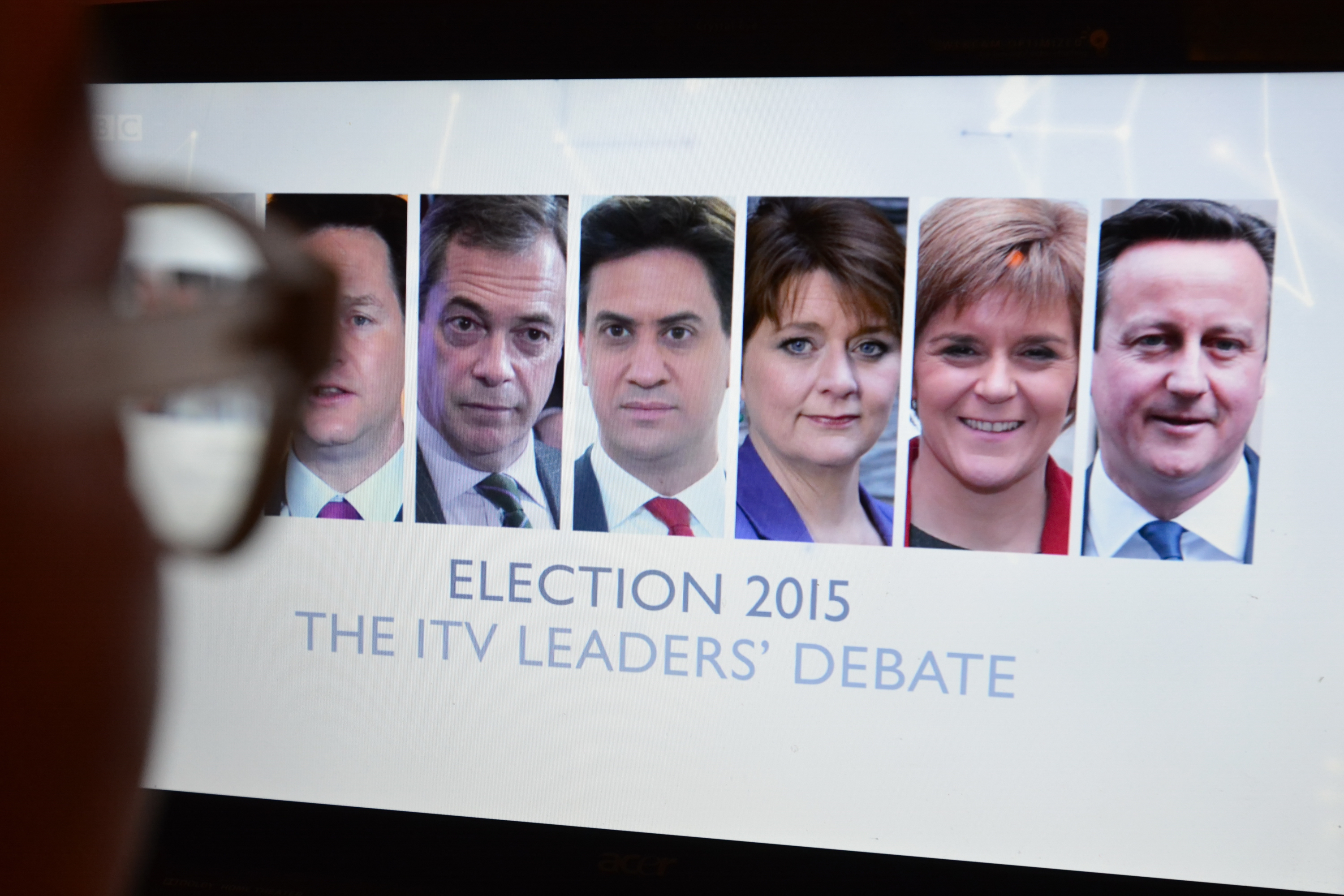

But if you want to transplant this model on to the 2015 general election, you’ll have to plan carefully.

There aren’t enough political parties to give more than a few participants a unique selection – and even if there were, the competition is not nearly as open. If you drew Class War, Yorkshire First or the Monster Raving Loony Party, your chances of winning would hardly compare to your colleagues who had drawn the Conservatives or Labour.

Even if there were enough selections, you’d have to decide what measure to base your sweepstake on.

Number of seats won by a single party

If you based the draw on seats, you’d pick a single party and provide a range of seats that it could win, giving ranges that suit the number of tickets you want to sell.

There are 650 seats to be won on May 7. If you chose the Conservatives, who currently hold 302 seats, you could sell 65 tickets split into sets of 10 seats (0-10, 11-20, 21-30, … 641-650). The people who draw the very low/high numbers might feel a little aggrieved, with only the ranges between 200 to 400 really feeling like they’re in with a chance.

If you feel this is a little unfair, then just sell tickets for a smaller range of outcomes – for example, 200-205, 206-210, 211-215…up to, say, 395-400. This would provide 40 tickets with (arguably) everybody having at least some chance to win.

To cover all eventualities, you could donate the money to charity if nobody wins, or sell two extra tickets that cover the cases where fewer than 200 or more than 400 seats were won.

Winners and losers

If you work with a winner/loser model, each ticket provides a party and a positive or negative number of seats won or lost, based on their current seat allocations. For example, one ticket would be marked Conservatives+1, another Conservatives+2, another Conservatives-1; and so on. The winning tickets for the different parties share the prize fund.

But if you focus on the three main parties, then you can only have three winning tickets. Of course, you can offer more or fewer prizes by extending or limiting the number of parties that you include in the draw.

Time of first return

There is always a race for constituencies to return their results first. You could have a sweepstake on who returns first, but if you sold 650 tickets there is only a small number of those that are realistic winners. The seat of Houghton and Sunderland South returned first in 2010, continuing Sunderland’s record of returning results quickly.

An alternative is to use the time that the first constituency returns a result. In the 2010 election, Houghton and Sunderland South declared at 22:52. You could have a reasonable sweepstake with the tickets being centred around 23:00 on May 7 and setting ranges, either single minutes, or more, depending on the number of tickets you want to sell. Outliers could be catered for in the same way that was suggested above for the number of seats won by a single party.

Just make sure that you have a single agreed way of getting the times. The BBC would make a good adjudicator, but whichever source you use, agree on it before the arguments begin.

Largest overall swing

You could assign a range of percentages using the number of increments needed to produce enough tickets – say from 5% to 30%, using increments of 0.5%, to make 51 tickets. The winner here is the person who holds the ticket that is closest to the largest swing by any political party.

Examples of large swings are out there if you need guidance on suitable ranges.

The law

It would be remiss not to point out the legal aspects of running a sweepstake. The good news is it’s okay – in the right circumstances.

This article by Professor Graham Kendall was published today Friday 1 May 21015 in The Conversation.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply