December 22, 2014, by Lindsay Brooke

Lessons learned in the 10 years since the Boxing Day Tsunami

The morning of the 26 December 2004 seemed like the start to a good day. It was Boxing Day, the day after Christmas Day, and foreign tourists were enjoying the sun and beautiful Thailand beaches. The Thai people were looking forward to welcoming in the New Year. They were unaware that a huge earthquake in the early hours of that morning, deep under the Indian Ocean, had triggered what would become one of the worst natural disasters in living memory.

At just before 8am local time a giant tsunami, a huge seismic sea wave, made landfall. It devastated the provinces of Phang Nga, Phuket, Satun, Krabi, Ranong, and Trang along the Andaman Coast. The highest death toll (78.3% of the total 5,395 including unidentified bodies) and number of homeless victims were reported from Phang Nga Province. In all over 230,000 from fourteen different countries were killed.

Using remote sensing technologies Dr Thuy Vu, a geospatial expert in the School of Geography at The University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, in collaboration with Dr Daroonwan Kamthonkiat at the Thammasat University in Bangkok, has been monitoring the recovery. Their research ‘Lessons learnt for Public Policy Maker from Relocation of Tsunami Affected Villagers in Thailand’ was presented at the European Geosciences Union General Assembly 2013, in Vienna.

A massive local and international emergency response and relief effort was deployed. So many nationalities were affected by the tsunami the world’s media descended on Thailand. They filmed and photographed the struggle to respond in the immediate aftermath of the tsunami.

Ten years on – is life getting back to normal?

With the help of international agencies the rescue and relief teams local people attempted to clean up the mess and restore life. Financial aid and donations poured in and were used to support the renovation of damaged houses and construction of new ones in the same and different locations.

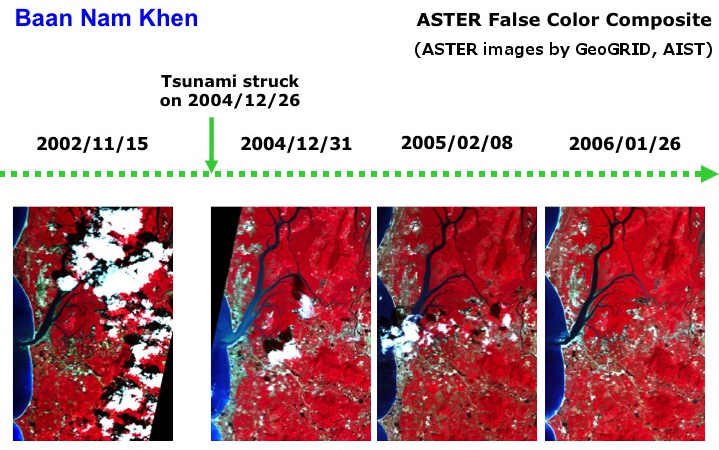

The remote sensing images taken by Dr Vu and Dr Kamthonkiat at the Thammasat University in Bangkok observed the recovery process from space. These reveal the timely synoptic changes on the ground.

Figure 1

The red colour represents highly covered vegetation. The areas along the coastline (to the left of the image) clearly showed the extent of the damage and the recovery. Land cover and land use changes could infer some activities on the ground but not a complete picture.

Figure 2

They observed with high-resolution satellite images (about 1m resolution) the changes at building level. But a newly built house cannot imply that life really is getting back to normal.

To find out what life is really like in the aftermath of such a devastating disaster you have to go there.

Between 2005 and 2010 they visited some of the areas seen with their remote sensing images and interviewed villagers in Phang Nga about the impact the tsunami had had on their lives and their rehabilitation.

Dr Vu said: “More than 1,600 houses were constructed in 29 locations and donated to tsunami homeless victims. Nevertheless, many fishermen villages stayed on illegally in the coastal zones. The government support for house construction and fishing equipment in the coastal zones had to be approved through a certificate of ownership. Others were forced to relocate but many tried to stay on illegally.

“Fisherman received free donated houses in alternative locations from the government and other charities in alternative locations. We wanted to know why they didn’t stay.”

Lessons learned

The researchers discovered that donated houses were located far from the coastal area – people had been moved to upper ground or rubber plantation areas outside tsunami inundated zone. But, basic facilities such as water, electricity and refuse areas were not fully established in some areas and the construction of new houses did not take into account other factors.

They found that fishermen living far from the shoreline and their boats turned to other work or unfamiliar jobs for their living. Some were jobless more than a year after relocation because they didn’t have the right skills, there was tough competition for limited vacancies and those that wanted to had no capital to start small businesses.

A few years after the relocation, the old and young generation became the major dwellers whereas much of the working generation went back to their previous villages to return to fishing. Some of them rented their donated houses to non-tsunami impact people or simply abandoned them.

Dr Vu said: “There was no proper plan for recovery and preparedness in the affected areas. Relocating outside of tsunami vulnerable areas was the right decision, but the criteria to come up with defining vulnerable areas are not simply the distance to shoreline and higher grounds – these are just critical physical factors.”

Are we better prepared for possible future disasters?

Dr Vu says a complete location analysis should be conducted before construction of houses for disaster impacted villagers. He said: “By using multi-criteria analysis on a Geographic Information System (GIS), proper location for new houses could be analysed based on any physical and socio-economic factors. Basic facilities (such as water, electricity and dumping area) should be sufficiently provided for in newly built housing areas. There should have been a better relocation plan for fishermen who wanted to continue fishing and proper skills training for those preferred a different way to earn for living after the tsunami.

“Career adoption programme also needs to be in line with the regional and local economic development, i.e. right skills for growing job markets. To make full use of donated houses for the right people, annual or continuous monitoring of tsunami impact villagers should be conducted by government sectors. By 2010 at least up to 80% of them had settled on their careers and adaptations.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply