June 3, 2013, by Nicola Royan

The drama of good government

Next Friday (June 7), I will be attending an extraordinary performance next Friday: an uncut production of Sir David Lyndsay’s Ane Satyre of the Thrie Estaitis at Linlithgow Peel. Ane Satyre is the first surviving play text in Older Scots: it is a personification play, most akin to Mankind , Everyman or even Magnificence. The protagonist is Rex Humanitas, a young man corrupted by fleshly desire (figured as sexual, but not exclusively so). Among the many features that make the play fascinating, however, is its multiple allegorical layers: for while Rex Humanitas can stand for an individual, his designation is as a ruler and his corruption is figured as regal, courtly, and, crucially, disastrous for his realm, implicitly Scotland. The play progresses from the individual to the king, to reformation by parliament (hence the three estates, the nobility, the church and the merchants or burgesses, all of whom are forced to confess to particular vices connected to their status), to a final act driven by the personification of Folly, suggesting that all human attempts at reform are doomed to failure. Folly’s participation is probably the most disconcerting intervention for a modern audience, although at least some of Lyndsay’s audience, as well as Lyndsay himself, would have been familiar with Erasmus’ Praise of Folly, and generally more comfortable with the imperfectability of the human race than we are.

This will be my fourth production of Ane Satyre: I have seen it done in a university union, in the Kirk’s Assembly Rooms and in my home town. All have been compelling, in different ways, all have attempted, however loosely, to reflect Lyndsay’s critique of government on to contemporary society, and all have offered me something to huff and puff about (very satisfying for an academic). Even the venues provided an interpretative angle: the university version stressed the humour over the serious satire, the Assembly Rooms emphasised the ways in which the play urges reform on the church (internal rather than Protestant), and Cupar (my home town) was where the first staging of the whole play took place in 1553 (although I favour a large car park as the play ground rather than the Castlehill. As I said, huffing and puffing).

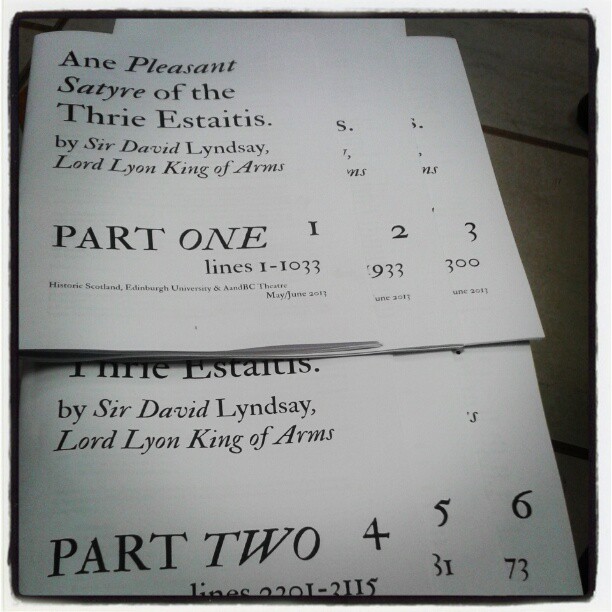

But this coming production will be different from all the others. It is part of a research project, designed to examine the effects of its original playing spaces on the text and its reception (http://www.stagingthescottishcourt.org ). As well as the productions at Linlithgow Peel, there are also productions of the Interlude, a rewritten shorter version for the court, at Stirling Castle and Linlithgow Palace. The version I will see will be uncut: this means that it will last about 5 hours (a straight read-through when I was a student took 4 hours). Like the full Hamlet, that requires stamina from audience and players, although like Hamlet, Ane Satyre always loses something wherever it’s cut. It will also be outdoors and during the day, as in its first Cupar production. Its location, Linlithgow Peel, will bring out its association with the royal court, particularly the court of James V and Mary of Guise. Lyndsay had begun his working life as an usher to the baby James V, and remained his devoted servant, with a licence to admonish, sometimes quite outspokenly, the adult king. As chief herald, Lord Lyon King of Arms, Lyndsay also understood the performance of government and rank, and this too is evident in the play. I too would like to understand the performance of government, particularly in the early sixteenth-century Scotland, and while I will never understand it as well as Lyndsay, I hope my fourth production of his play will get me further. I urge you to join me, if you’re in the vicinity: see the website above and that of Historic Scotland (http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/events-calendar/event_detail.htm?eventid=38810). In the midst of more contested allegations about political corruption, the play will make you think in a new way.

Image copyright Staging the Scottish Court.

Just to follow up: the performance was excellent! The Vices brought out some very effective adlibbed and physical comedy, the Virtues (Verity and Chastity) were just a little bit annoying (as they have to be, otherwise Sensuality wouldn’t be nearly so attractive). All kinds of lines and sections made their point: Lyndsay had an excellent sense of stagecraft!