January 4, 2024, by Chloe

Meet the Participants

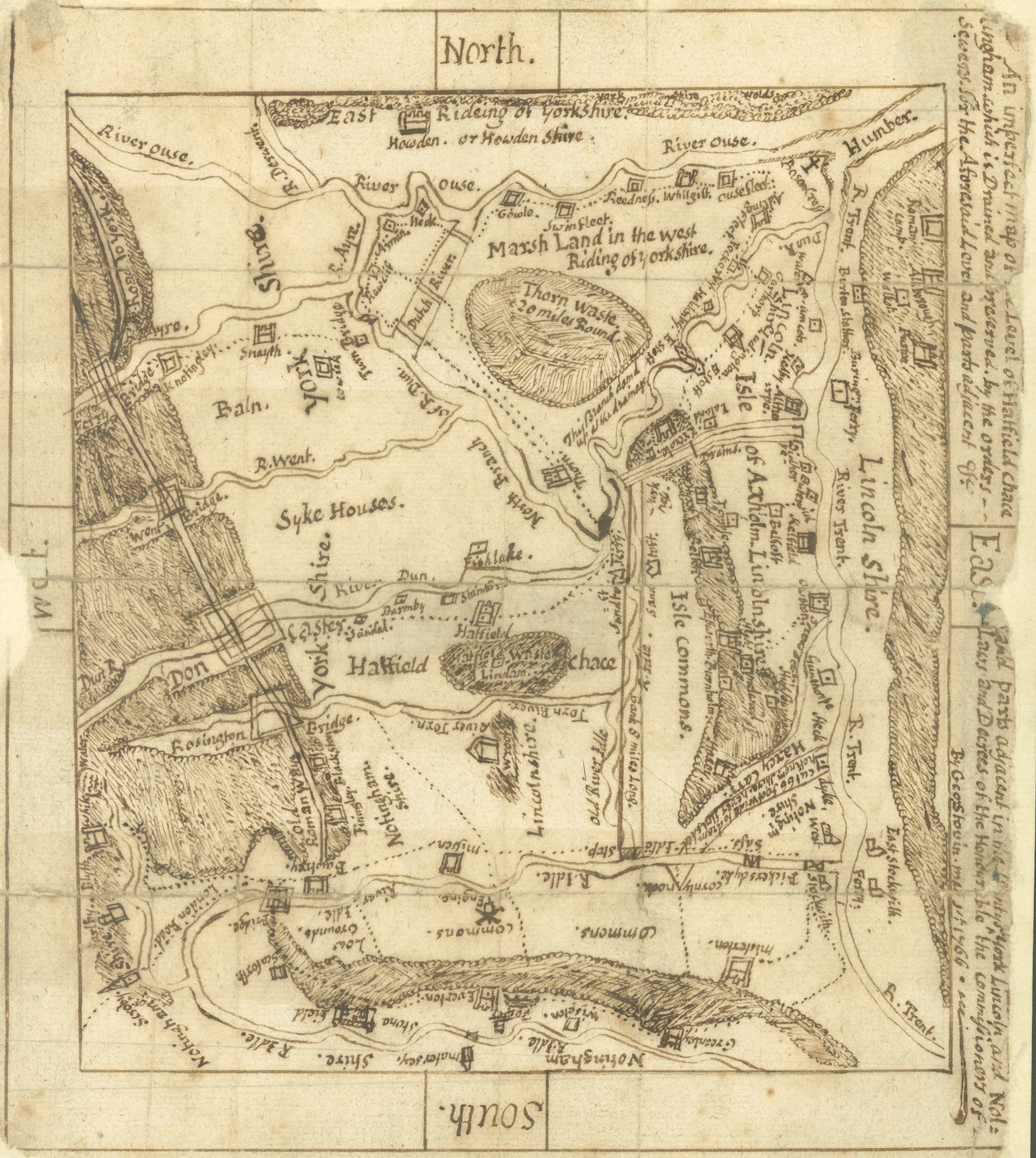

Hatfield Chase, a low-lying marshland straddling Lincolnshire and Yorkshire, once teemed with wild birds, fish and deer – the pursuit of many a party on this royal hunting ground. However, by 1626, Charles I had drained the nation’s coffers and sought an innovative solution to his financial woes: employing another Charles (Vermuyden, a Dutch engineer) to oversee the drainage of this part of his estate, so it could be put to agricultural use.

This transformative project seems to have captured the interest of George Stovin of Crowle, Lincolnshire (1965/6-1780), inspiring him to create a manuscript recounting the tale of the drainage, featuring extracts from related documents. The text is particularly valuable as it gives us insight into both this technological feat and into the lives of those affected by it, which we would otherwise be unable to access.

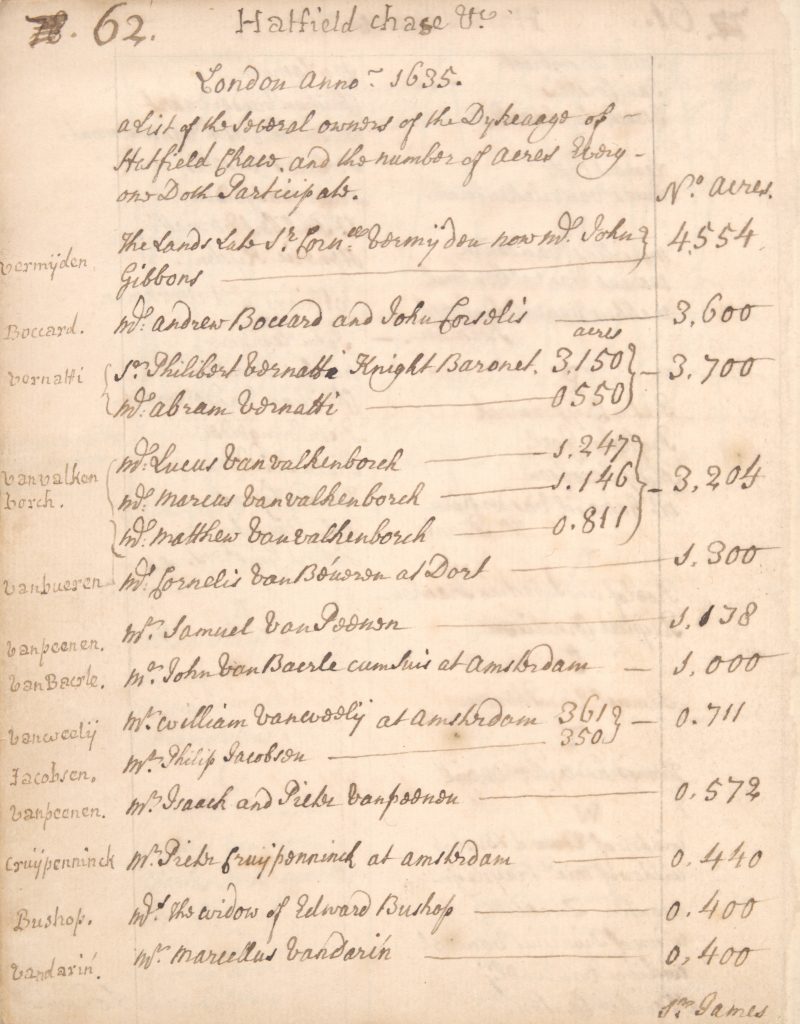

One of the documents included in his compilation was the list of ‘Participants’: the individuals brought over to England by Vermuyden to undertake the project. Many of these people were Dutch, or else Huguenots (French Protestants). The influx of these newcomers – who, according to an agreement with Charles I, would be entitled to a third of the land once it was drained – caused significant tension with the locals, who felt themselves to be dispossessed.

List of the Participants in the Level of Hatfield Chase in Yorkshire, Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire in 1635, showing the acreage to which each was entitled, from Page 63 of Stovin’s Manuscript, HCC 9111/1

Stovin’s account provides great detail about the sabotage, violence and even death that resulted from this ill will: for instance, he suggests that during the Civil War the people of Epworth and Misterton were inspired to take up arms against the King primarily on the basis of this grievance, laying waste to the newly enclosed lands.

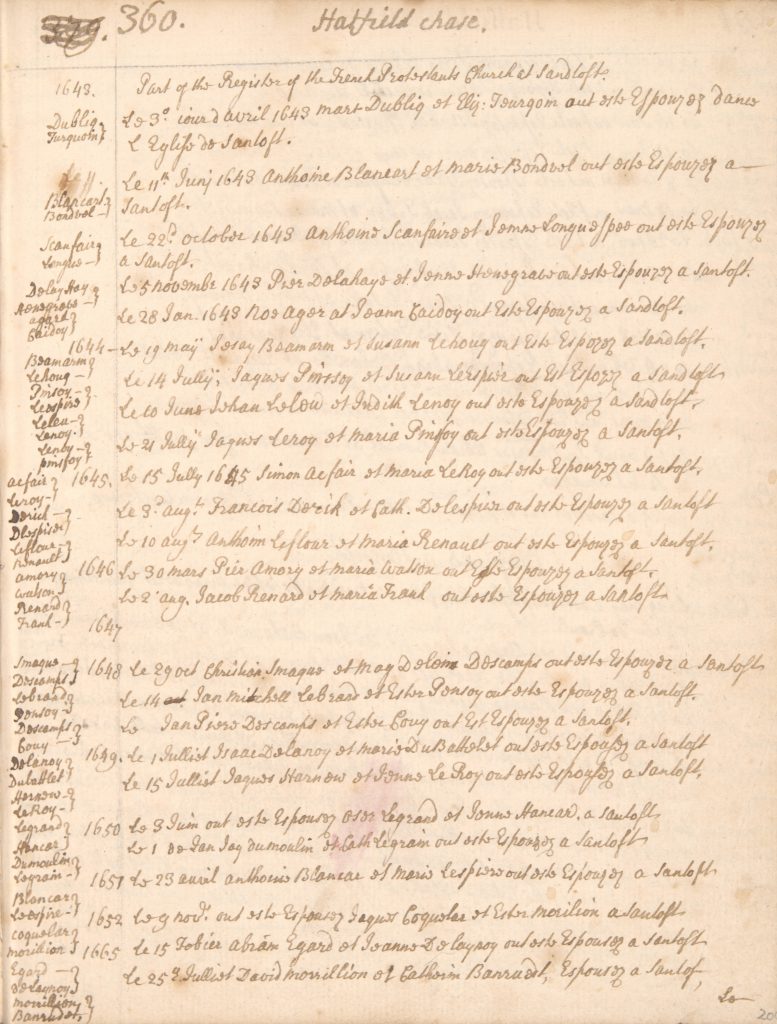

But the destruction did not stop there. According to Stovin, the locals went on not only to damage the drainage infrastructure, but also to deface a church at Sandtoft which had been built ‘for the use of the Dutch and French Protestants inhabiting [the Chase]’. The nature of the vandalism suggests that the feud was deeply personal: in addition to stealing the furniture, the rioters actively sought to desecrate the chapel, for instance by burying carrion under the communion table.

There were continuing flare-ups of violence, and a considerable number of legal challenges, until the combination of the 1714 Riot Act and the 1719 dismissal of the Commoners’ case against the Participants brought both to an end.

Extracts from the register of the Church at Sandtoft from Page 360 of Stovin’s Manuscript, HCC 9111/1

Stovin’s manuscript not only relates the ruin of the church at Sandtoft, but also the day-to-day fabric of Huguenot religious life, via the inclusion of a partial register of baptisms, marriages and burials conducted at the church from the 1640s to the 1680s. This is an invaluable record, as the whereabouts of the original remain sadly unknown.

Speaking of lost documents, Stovin’s Manuscript was rediscovered in 1880, a hundred years after his death, at a local solicitor’s office. It was found alongside a proposal for printing and distributing the work by subscription, suggesting that he intended it for public consumption – making the fact that it had lain forgotten for so many years all the more affecting.

Happily, it is now available for consultation at the Manuscripts and Special Collections Reading Room. To find out more, or to book an appointment today, please contact us at mss-library@nottingham.ac.uk.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply