June 25, 2020, by Nicholas Blake

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them

In the 17th and 18th centuries, a time before Instagram, National Geographic, or even David Attenborough, there was great interest amongst Europeans in the animals which roamed distant realms. These fantastic beasts were eagerly read about in publications written by explorers brave enough to adventure to far-off lands, with detailed engravings made from eye-witness accounts or hurried sketches, often with dubious accuracy.

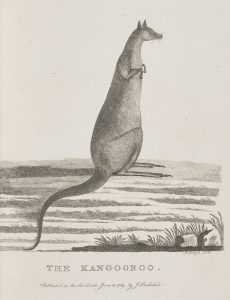

In 1788 the ‘First Fleet’ of British ships stocked with convicts arrived in New South Wales, Australia, to establish a penal colony, led by Captain Arthur Phillip. The voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay, published 1789, documents his and other naval personnel’s journals and reports of this strange new land, including encounters with the natives and fantastic beasts. One such animal was spotted in New Holland: the “kanguroo” (sometimes spelt as “kangooroo”). These creatures are described as being “so shy that it was difficult to shoot them”, though the author also suggests that “when their proper food shall be better known, they may be domesticated.” The beast was regarded as dangerous, with the book noting that “the tail of the kanguroo, which is very large, is found to be used as a weapon of offence, and has given such severe blows to dogs as to oblige them to desist from pursuit”, but not considered worthwhile for eating: “its flesh is coarse and lean, nor would it probably be used for food”.

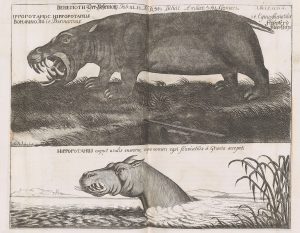

The authors of books about foreign lands hadn’t necessarily been to the locations themselves, instead relying on the testimony of those who had, trusting their every word implicitly and publishing without even including the magical get out clause, “citation needed”. Hiob Ludolf, a 17th century German orientalist, published Historia Æthiopica, a study of Ethiopia, in 1681. Ludolf never actually went to Ethiopia, gaining his knowledge of the country from his friend Abba Gorgoryos (Father Gregory), an Ethiopian priest and expert in language, and relates the tales of the fantastic beasts as described to him.

One of these creatures was the hippopotamus, expressed (in a later English translation) as “a vast bulk of flesh, and of a prodigious strength […] They overturn small boats, which renders all passage by water very unsafe to the inhabitants, in regard they lye in wait for the men themselves”. Ludolf suggests the Greeks may have given the creature the name “hippopotamus”, or “river-horse”, due to only seeing the head above the water; “for his snowt, nose, and especially his ears are like to those of a horse. But the shape of his body and feet is altogether different; and beside that, he wants a mane.”

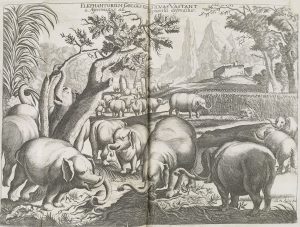

Other animals included in Ludolf’s Historia Æthiopica include sheep with tails “so far and ponderous […] that the owners are forc’d to tye a little cart behind them […] to ease the poor creature”, and elephants who “shake trees bigger than themselves in bulk […] till the whole tree be torn up by the roots, as with an earthquake”, but who are also docile and afraid of men: “The elephant never offers to attempt upon any person, unless provok’d; if he be threatn’d with sticks or cudgels, he hides his probosces under his belly, and goes away braying; for he is sensible it may be easily chop’d off.”

Illustration of a sheep with its large tail resting on a small cart, from “Historia Æthiopica” by Hiob Ludolf, 1681.

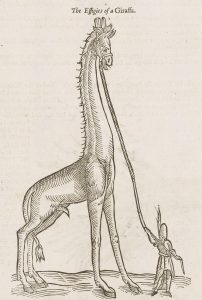

In some works, European readers were exposed to incredible imagery of both real beasts and imaginary ones, presented side by side. In his discourse of animals within The works of Ambrose Parey, 1691, Parey wrote about many fantastic beasts from around the world. Some are very recognisable, such as the “giraff”, found in India, “beyond the River of Ganges, some five degress beyond the Tropick of Cancer”. It is described as being “not unlike our Doe”, but with a six foot long neck and “exceedingly beautiful” skin; “he feeds upon Herbs, and Leaves, and Boughs, of Trees; yea, he is also delighted with bread”.

A walrus-like creature seen around Scotland is described as a “Sea-Elephant” because of its “two teeth like to Elephants”, and is often seen lounging on rocks, where “he sleeps so soundly”.

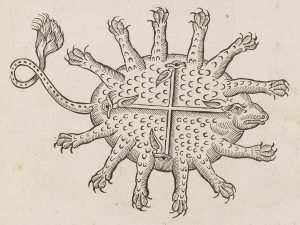

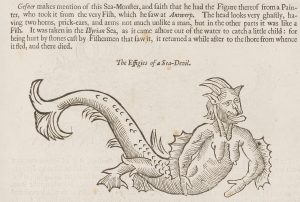

Interspersed with these plausible creatures are illustrated a myriad of sea-beasts, some part-man, part-fish, and some – like the African “Tortoise”– made up of four eyes and twelve feet, “by whose help he can go any way he please without turning of his body”, or the “Sea-Devil”, seen at Antwerp, with two horns, pointy ears and arms – and the rest like a fish. Supposedly it came ashore “to catch a little child”, before having stones flung at it by fishermen and retreating “to the shore from whence it fled, and there died”.

Illustration of a strange tortoise like creature with six pairs of arms and four eyes, from “The works of Ambrose Parey”, 1691.

Nowadays, technology proves to us that there are some remarkable creatures around the Earth, lurking in the depths of the oceans. But a few hundred years ago books like these were the only connection Europeans had to fantastic beasts, illustrating a unique view of the world at a time when anything and everything could exist, out there, somewhere.

The books illustrated here are held at Manuscripts and Special Collections. We are currently closed due to the Coronavirus, but once we reopen, they will be available to view by anyone upon request in our Reading Room at King’s Meadow Campus.

- The voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay / by Arthur Phillip (London : [1789])

Special Collection Oversize DU172.P58 (SC74180) - Iobi Ludolfi aliàs Leut-holf dicti Historia Æthiopica / by Hiob Ludolf (Frankfurt am Main : [1681])

Special Collection Oversize DT377.L8 (SC58440) - The works of Ambrose Parey (London : 1691)

Med-Chi Collection Oversize WZ240.P25 PAR (600199473X)

Find these items and more using NUSearch. For more information, including when we are open and for contact information, please see www.nottingham.ac.uk/mss.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply