July 18, 2018, by Kathryn Steenson

Women’s Suffrage in the D H Lawrence Collection

One hundred years after the ‘Representation of the People Act’, which awarded the vote to women over the age of 30 who owned property, it seems like a good time to rediscover some gems from the archives that provide intimate snapshots of the fight for the vote.

Louisa ‘Louie’ Burrows, a friend and onetime fiancée of D H Lawrence, on whom he based the character Ursula in The Rainbow (1913), has several boxes of her correspondence in the D H Lawrence collection. Contained within are some fascinating references to women’s suffrage. Although Lawrence’s own stance on the issue, as well as his attitude towards women more generally, is somewhat debated, his letters to Louie indicate some sympathy with those involved in the cause.

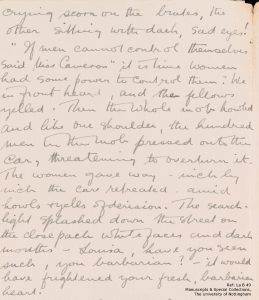

Writing to Louie in 1909, Lawrence offers a vivid description of the tensions between anti-suffrage mobs and, somewhat hyperbolically, ‘Suffragettes in thousands and tens of thousands’ prior to a controversial by-election in Croydon. In one incident, Lawrence found himself in the middle of a mass of men intimidating two Suffragettes campaigning from their car. One responded to the mob with scorn:

“‘If men cannot control themselves’, said Miss Cameron, ‘it is time women had some power to control them’.”

Infuriated by this, the mob heckled and jostled the women, threatening even to overturn the car.

In typical Lawrence fashion, his letter uses this dramatic vignette to launch into a broader comment on social ills, concluding that ‘life is not gentle, and amusing, and pleasant’. Despite, or because of this literary flourish, this letter demonstrates how difficult and even dangerous the struggle for the vote could be, and how fierce anti-suffrage feeling was among many areas of the population at this time.

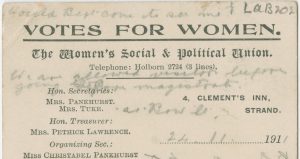

If Lawrence’s experience is evocative through its description, another piece of post received by Louie is even more so for the story behind it. A postcard, sent on the 24th of November 1911, sporting the printed slogan ‘Votes for Women’ and the details of the WSPU, was sent by an M. Stewart (likely Mary Stewart, whose sister Nina was a college friend of Louie) from Bow Street Prison.

Postcard from M[ary] Stewart, Bow Street Police Station to Louie Burrows, Leicestershire; 24 November 1911. Ref: La b 202

Mary asks that letters be sent to the WSPU headquarters at Clement’s Inn, where she has been waiting for two days for a magistrate’s hearing. She enquires whether Louie’s mother would be willing to take in a prisoner discharged from Holloway—presumably a fellow suffragette – rather suggesting that the Burrows as a family may have been active participants in the cause. Despite her impending trial, Mary seems to relish her opportunity to mix with her fellow campaigners:

“Have made the acquaintance of Miss Pethick. Glad to have come here. Never had before an opportunity of meeting so many fine women.”

The date and origin suggests that Mary was among the 229 campaigners for women’s suffrage arrested in the wake of the mass window-breaking of Government buildings in London on November the 21st 1911. This was a significant moment in the Suffragette’s increasing militancy.

The ‘Miss Pethick’ mentioned is Mrs Pethick-Lawrence, who founded the publication Votes for Women in 1907 with her husband. The couple were arrested and imprisoned in 1912 as a result of the Suffragette’s new tactics, even though they neither approved of nor participated in the window-breaking. The Pethick-Lawrence’s luck didn’t improve even upon their release; they were ousted from the WSPU almost immediately for their disapproval of the new tactics.

Another Suffragist associated with Lawrence, and who was rumoured to have inspired the character Clara Dawson from Sons and Lovers (1913), was one Alice Dax. Alice, born in Eastbrook, is described in vibrant detail by one Enid Hilton. Enid describes Alice’s life, striking appearance, and idiosyncrasies of behaviour so thoroughly that, reading it, you feel as if you know her. Above all, Alice was characterised by her lack of inhibition, confidence, and ‘intelligence and vitality’, which apparently intimidated most men:

“It was less a personal fear than a sex-wide fear of the dominant and secure male for the emerging independent female who would so soon upset his monarch-of-all-he-surveys existence”.

Enid recounts how her mother and Alice, who were great friends, both “worked for the women’s cause”, meeting with many of well-known names from the suffrage movement, including the Pankhursts. What emerges is a very personal insight into the ongoing efforts and experiences of those fighting for women’s rights—local meetings, conversations late into the night, and green, purple, and white flags.

Page from a biographical account of Alice Dax by Enid Hilton; n.d. [c. early 1940s]. Ref: Hil 2/12/3

This is a guest post by Thea Lawrence, PhD student from the Department of Classics at the University of Nottingham. The original records discussed here are held in Manuscripts & Special Collections. To find out more about our collections, including those relating to D H Lawrence, or to access our collections, please contact us on mss-library@nottingham.ac.uk.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply