July 5, 2018, by Kathryn Steenson

Happy Birthday, NHS!

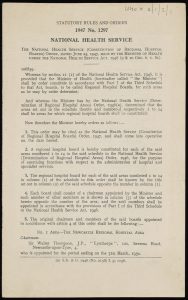

On 5th July 1948 the Secretary for Health Aneurin Bevan officially launched an ambitious new service: the National Health Service.

At its core were three principles:

Good health for all: an examination of the Government’s proposals for a National Health Service (London, 1944). Fred Westacott Printed Collection Pamphlet RA412.5.G7.G6, barcode 1007261602.

- That it meet the needs of everyone

- That it be free at the point of delivery

- That it be based on clinical need, not ability to pay

At the moment of its birth, the NHS immediately became Britain’s third largest employer with approximately 364,000 staff across England and Wales (compared to roughly 1.5 million staff today).

Before the National Health Service patients were generally required to pay for their health care, provided by a confusing array of different organisations and covered by a hotchpotch of private and public schemes. Charities, local authorities, voluntary hospitals and occupational welfare societies all provided different types of healthcare for different people under different rules.

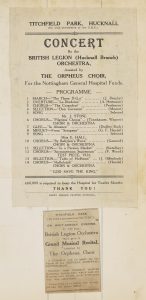

One of these organisations was the Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Hospital Saturday Fund, which began in 1873. The purpose was to raise subscriptions from local firms or through charity fundraising events, which would then be given to various local medical charities, among them the General Hospital, the Children’s Hospital, the Women’s Hospital, the General Dispensary, Eye Infirmary and the Samaritan Hospital.

Concerts were a popular way to raise money through ticket prices and collections at the events, and the advertisements were not averse to trying to guilt people into supporting them; a poster from the 1920s reminds residents of Hucknall that patients from their community cost the General Hospital £1,500 in 1925, about £700 more than they had subscribed.

By 1938 there were 1700 local firms participating in the scheme. Contributors could obtain free medical aid at the hospitals included in the scheme. By 1947, the number of contributors had risen to 137,387, a significant proportion of Nottingham’s population.

Early minutes of the Fund (later volumes are closed for 100 years to protect patient privacy) show the committee debating the appeals in difficult cases where the Fund initially refused to pay medical costs: a difficult maternity case that cost more than anticipated, whether a cancer patient’s sudden turn for the worse was considered an emergency case (and therefore covered) or a chronic case (and therefore not).

To modern sensibilities these local hospitals had very odd criteria for admission. Patients were often required to provide a surety to cover burial costs in case of their death, which must have been incredibly reassuring. Some hospitals even specified what garments patients needed to provide on admission. Even in the 1920s the Hospital Linen Guild was established at Nottingham General Hospital to provide patients and staff with the garments they needed, such as pyjamas, babies’ vests, and surgical gowns and masks, and provide the Matron with funds to buy sheets, blankets and quilts. Sewing groups gave help in kind, and cash was raised through subscriptions collected by members. Post-NHS, and with the Hospital’s services changing, the charity adapted to provide furnishings and fittings on the wards, and later tackled projects such as purchasing a minibus for elderly and infirm patients in the 1980s.

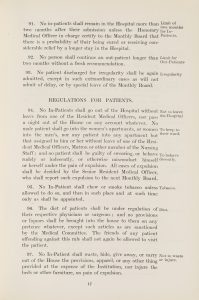

The character of the medical care provided also changed over the years. When the General Hospital opened in 1781 rules had governed how long in-patients could stay before they had to reapply (two months). Domestic servants and soldiers could only be admitted if their superiors agreed to pay for their treatment, and the hospital did not admit pregnant women or children at all. Pregnancy and birth were considered a normal aspects of women’s lives and not requiring special care. When women and children did fall ill, it was believed that they should be cared for at home by family and friends.

This changed in the 19th century when special hospitals for women and children opened, but the vulnerability of babies and young children was one of the arguments used to support the NHS. Some private health insurance schemes offered by employers restricted healthcare solely to the workers, or placed restrictions on what dependents were entitled to.

The phrase ‘National Health Service’ was first used by Dr Benjamin Moore, in 1910’s The Dawn of the Health Age [full text available online but may require institutional log-in]. Moore argued that the entire health system needed remodelling to save lives and money through preventing disease rather than attempting, with varying degrees of success, to cure them. Two decades later, A. J. Cronin, himself a doctor, explored medical ethics and criticised the existing healthcare system in his 1937 novel The Citadel, in which a doctor from a Welsh mining village leaves for a private practice in London. These publications are credited with establishing public support for a nationalised health service, but it wasn’t until the outbreak of WWII that there was the political impetus to act. The Emergency Hospital Service was created in 1939 to treat potential casualties of war, and gave a practical demonstration of a centralised, state-run health service. Less than a decade later, the NHS was born.

More information about our Health and Hospital collections is available on our website, and if you would like to visit the Reading Room to see our archives and rare books, please contact us to make an appointment. You can also follow us on Twitter @mssUniNott and read our newsletter Discover.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply