September 19, 2014, by Kathryn Steenson

The Morning After the Nay Before

For anyone who has somehow missed the extensive – and sometimes heated – campaign, this morning the results of the Scottish Independence Referendum were announced. The Union between Scotland and England has been in force since May 1707, after both the Scottish and English Parliaments had passed their own separate Acts ratifying the Treaty of Union.

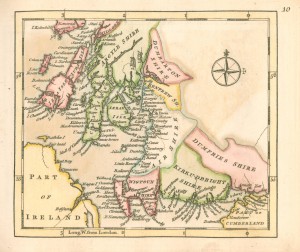

The two countries had shared a monarch since 1603, when James VI of Scotland succeeded his cousin Elizabeth I of England to become James I of England. Previous attempts had been made to unite England and Scotland, both by force (during the military campaigns of the Wars of Scottish Independence in the 13th and 14th centuries) and by political negotiation (especially from the 15th century onwards).

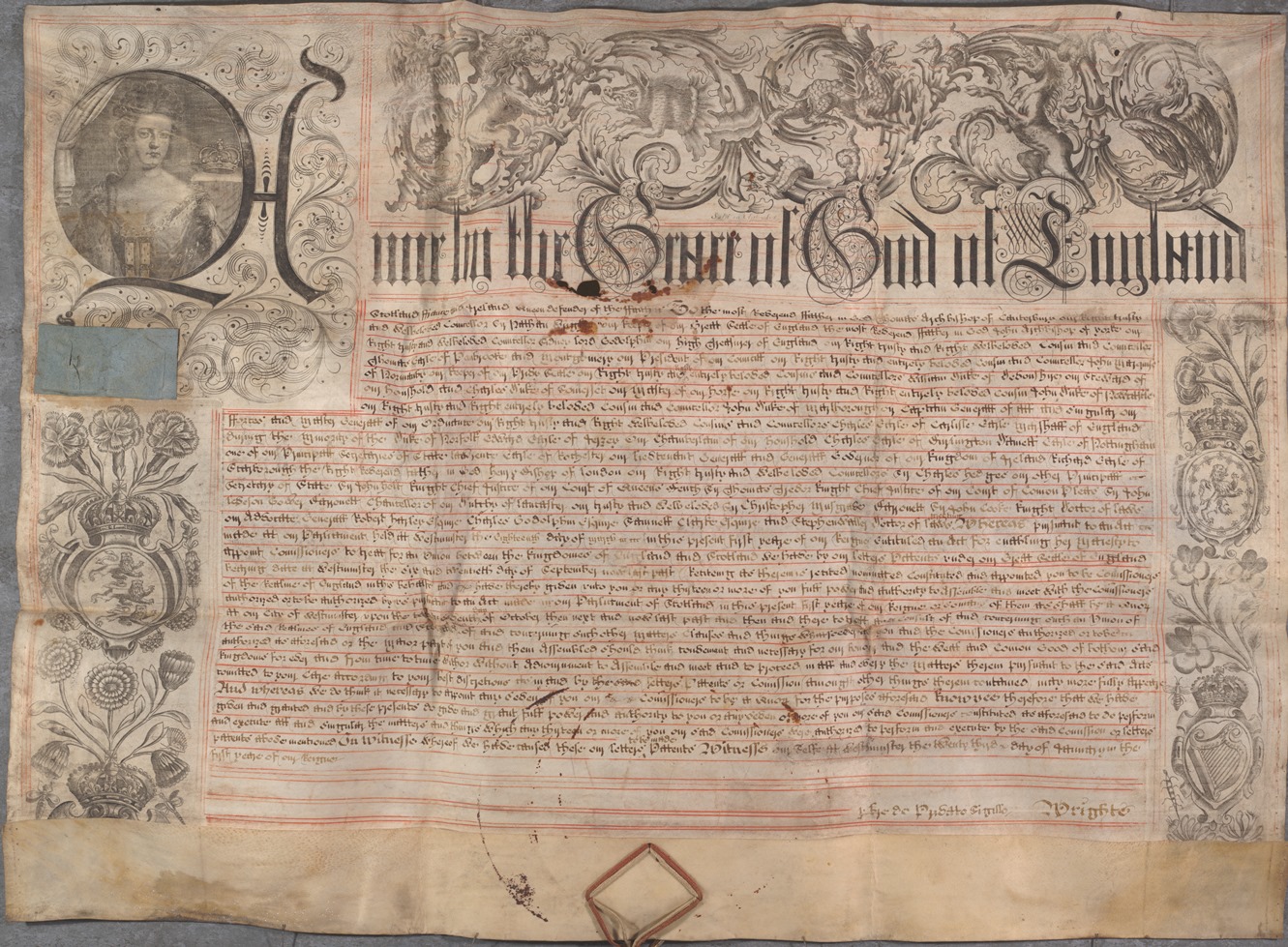

The ultimately successful negotiations were conducted by 31 commissioners sent from each country, the majority of whom supported the union. Among the contingent from Scotland were James Ogilvy, 1st Earl of Seafield and Lord Chancellor, and James Douglas, 2nd Duke of Queensberry and Lord Privy Seal. England sent William Cowper, 1st Baron Cowper and Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, and John Holles, Duke of Newcastle and Lord Privy Seal. The document below is a letters patent, an order published by the monarch, appointing commissioners to negotiate for the union with Scotland dated 23 January 1703. Queen Anne’s portrait is in the historiated initial, and although not visible in this image, her Great Seal hangs on the red and white cord. Holles’s granddaughter married the Duke of Portland, which probably explains why this document (Ref: Pl /F/1/1/18) is in our Portland Collections rather than the Newcastle Collections.

Negotiations began in April 1706 and concluded in July. The union is a complicated and divisive issue, and why this attempt was successful when so many others had failed is not easily summarised in a few hundred words. At a basic level, England wanted political stability and Scotland wanted financial stability. England feared that an independent Scotland, with a separate monarch, would make alliances with other European countries that would be detrimental to England’s interests. Scotland was poorer, had fewer trade links than England and England’s extensive colonies, and had suffered heavy financial losses due to the failure of their attempts to establish a colony in the 1690s. A union meant England would invest in Scotland and open up trade opportunities.

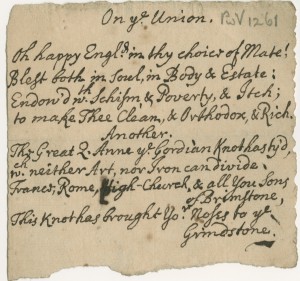

Even though the two states were united, it was not a universally popular decision in either England or Scotland. It found far greater support amongst the nobility than the general population, especially in Scotland. These two short poems (Ref: Pw V 1261), both entitled ‘On the Union’, were written shortly after the union, by an unknown but presumably English author. The second poem in particular highlights the feeling that two united Protestant countries, under a Protestant monarch, would be stronger against (real or perceived) Catholic influences:

“Oh happy England in thy choice of Mate!

“Oh happy England in thy choice of Mate!

Blest both in Soul, in Body & Estate;

Endowed with Schism & Poverty & Itch

To make Thee Clean, & Orthodox, & Rich”.

“The Great Queen Anne the Gordian Knot has ty’d,

Which neither Art, nor Iron can divide,

France, Rome, High Church & all you sons of Brimstone,

This Knot has brought your Noses to the Grindstone”.

It has been a rocky three centuries, and the fact that the referendum on Scottish Independence was called indicates that the union is still very much a contentious issue. An overwhelming majority of those registered to vote did so, and the Scottish people have finally had the chance to vote whether or not to stay part of the United Kingdom. By a very narrow margin (45% to 55%), they have decided to remain part of the union.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply