November 5, 2013, by Kathryn Steenson

Gunpowder, Treason & Plot

Four hundred and eight years ago, people in England awoke to news that a terrible plot to assassinate the King and his Parliament had been foiled. It gripped the popular imagination then, and today we still mark the anniversary of the Gunpowder Plot with bonfires and fireworks.

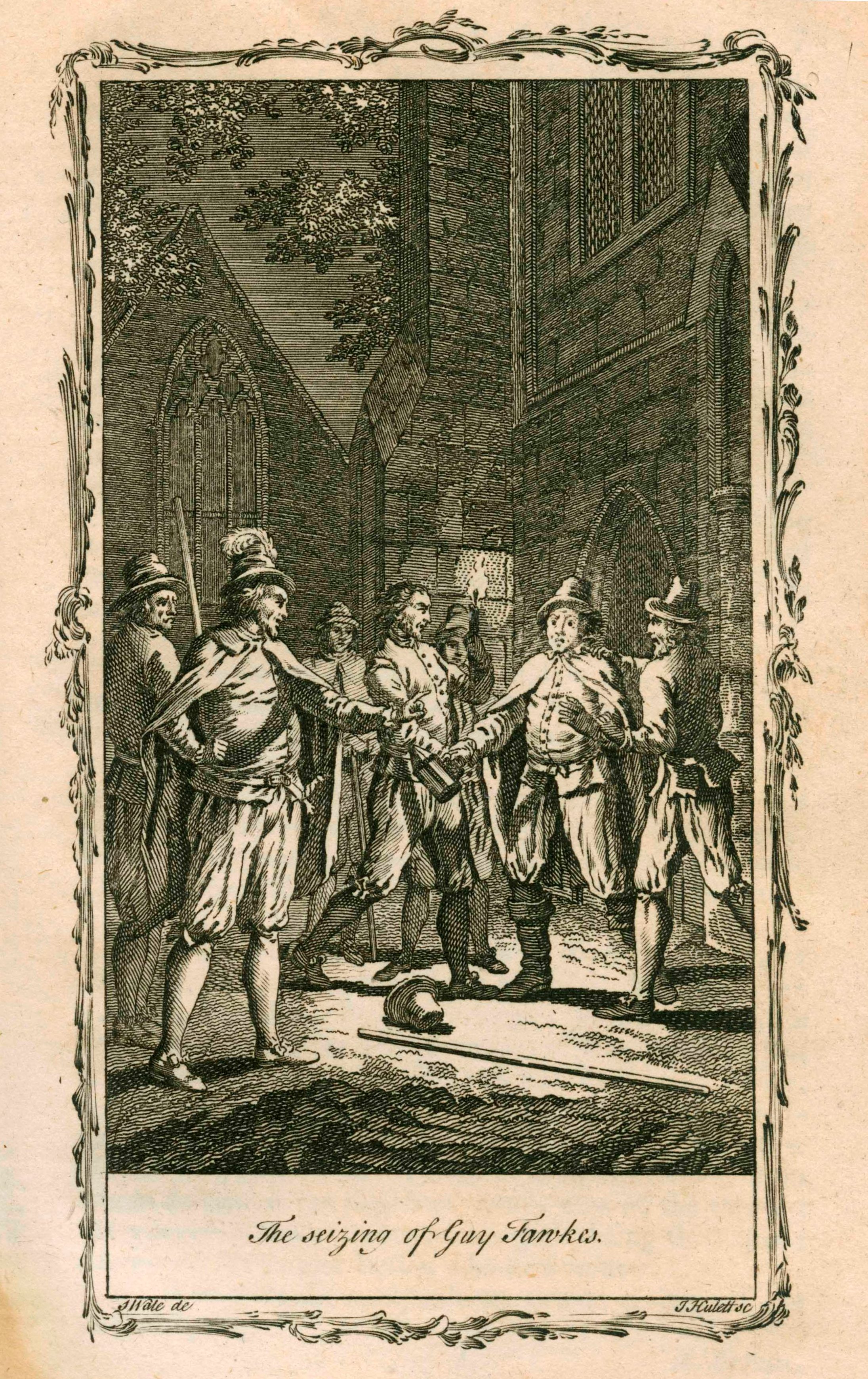

This engraving is taken from a children’s educational book, “A Complete History of England: by question and answer: from the invasion of Julius Caesar to the year MDCCLXVI [1766]” (Briggs Collection LT109.DA/C6). It depicts, probably very unrealistically, the dramatic moment when Guy Fawkes was discovered and the plot stopped.

At around midnight on the 4th November 1605, guards searching the cellars and undercrofts below the Houses of Parliament apprehended a man who gave his name as ‘John Johnson’. There were 36 barrels of gunpowder in the cellar, more than enough to reduce the buildings above to rubble and kill the King and his Parliament.

The search had been prompted by an anonymous letter received by William Parker, 4th Baron Monteagle, a little over a week earlier, warning him to avoid the opening of Parliament. Although the author has never been conclusively identified, it is generally though that it came from Francis Tresham, one of the plotters and Lord Monteagle’s brother-in-law.

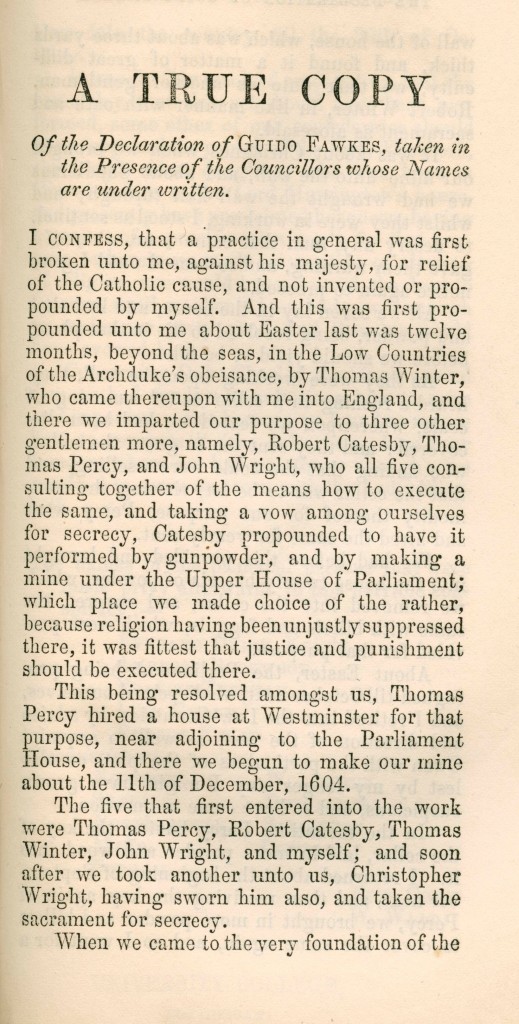

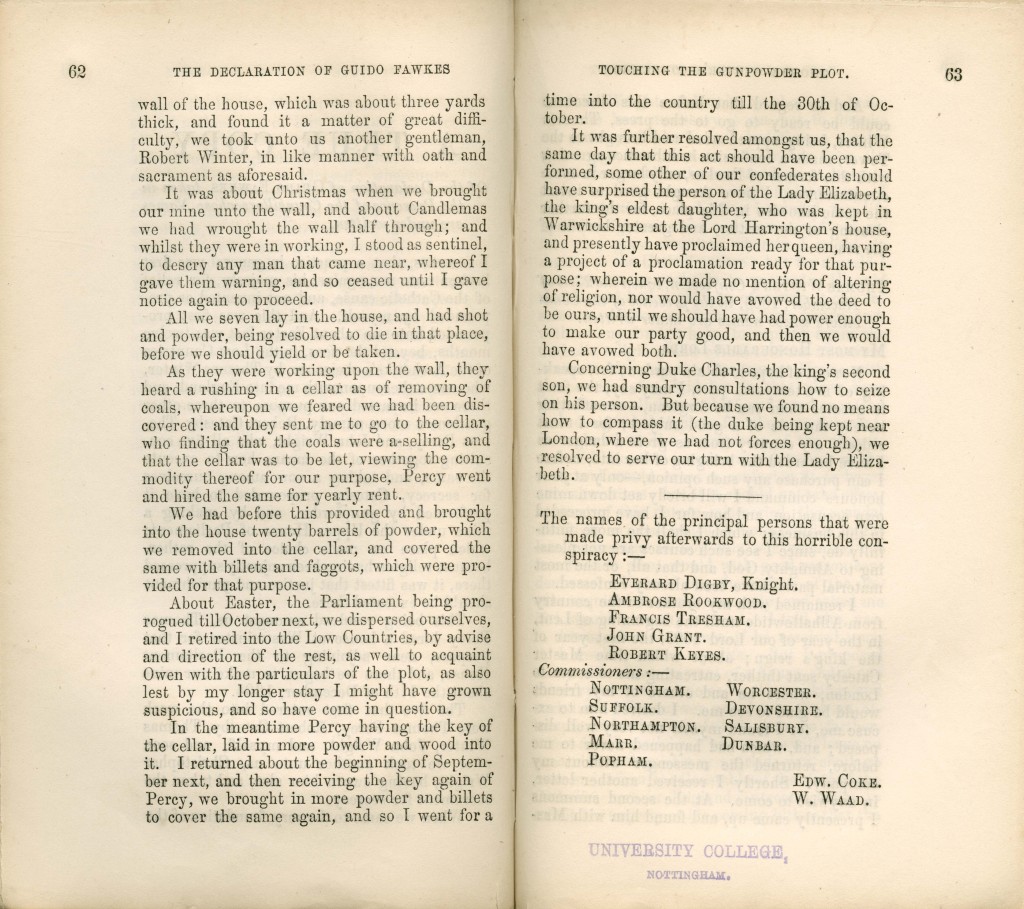

For two days, ‘Johnson’ gave the authorities no information, and only broke when subjected to severe torture. His real name was Guy Fawkes, a Catholic convert born in Yorkshire in 1570. Fawkes had fought for Catholic Spain in the Eighty Years War against the Protestant Dutch, and had been recruited for his experience using explosives. According to his confession, his role was to light the fuse, after which he would escape to Europe whilst his co-conspirators would kidnap the king’s nine-year old daughter Elizabeth, and “have proclaimed her Queen…[without] mention of altering of religion, nor would have avowed the deed to be ours, until we should have had power enough to make our party good”.

Even with his silence, the other identities of some of the thirteen conspirators would have been relatively easy to discover. Thomas Percy had leased the undercroft using his real name and several of the others, including Robert Catesby and John and Christopher Wright, had been involved in previous Catholic rebellions. In the aftermath of discovery, the group fled to the Midlands, where several were killed resisting arrest. The trials of the surviving eight conspirators began in January 1606.

Such was the public appetite for news that the confessions of both Guy Fawkes and Thomas Wintour were first printed within a few weeks of their arrest. This slightly later volume, “The Gunpowder Treason” (Special Collection DA392.G8), includes the confessions; copies of speeches made at the trial and by King James; and copies of writings made by the only conspirator to plead guilty, Everard Digby, during his imprisonment. His guilty plea elicited no mercy; he and the others were all hanged, drawn and quartered.

As this volume was published in 1679, the anti-Catholic sentiments are assumed to be familiar to the audience. There is limited discussion of the context of the hostility from some Catholics, who made up approximately 5% of the population. Since Henry VIII’s split from the Roman Catholic Church in the 1540s, England had veered between Catholic and Protestant monarchs, with persecution and repression from both sides. Elizabeth I had initially tolerated Catholicism, as long as they were discreet in their practices and loyal to her. After a Catholic uprising in 1569, the Pope’s excommunication of her the following year, and the attempted invasion by the Spanish Armada in 1588, she viewed Catholicism as a personal threat and her attitude hardened. Catholic Mass was prohibited and there were fines for failure to attend Anglican services, and some priests and those who harboured them were executed for treason.

Towards the end of her reign, it became clear that Elizabeth’s successor would be James VI of Scotland. He was Protestant but his mother, Mary Queen of Scots, had been Catholic, and English Catholics were initially optimistic that he would be sympathetic. Their hopes were dashed when he reintroduced penalties for recusancy shortly after he took the throne. Far from improving life for Catholics, the Gunpowder Plot resulted in even more stringent laws being passed, forbidding them from voting and practicing law.

Books in Special Collections can be searched through the library catalogue. To view our holdings, including those in Briggs Collection of Children’s Educational Literature and general Special Collections, please make an appointment to visit our Reading Room on Kings Meadow Campus.

[…] it seem rather dry and worthy, but it contains some real treasures and we’ve mentioned it in several previous […]