January 9, 2025, by Nicholas Blake

Einstein a Go-Go: When Albert Gave a Lecture at University College Nottingham

In a teaching room within the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Nottingham hangs a blackboard, protected by a perspex sheet. This blackboard contains theoretical equations written on it by legendary physicist Albert Einstein during a lecture he gave at the University (then University College Nottingham) on 6 June 1930.

Using archives, articles and other publications held at Manuscripts and Special Collections, this blog tells the story of Albert Einstein’s visit to Nottingham.

Photograph of the blackboard used by Albert Einstein when he gave a lecture at University College Nottingham, 6 June 1930. (NUP/2)

The Friend

The visit was organised by Einstein’s friend, fellow physicist Henry Brose (1890-1965).

Brose worked at (and became head of) the Physics Department at University College Nottingham between 1927 and 1936. Born in Australia to German parents, he was arrested by German authorities while visiting relatives in Hamburg in 1914 and held as a civilian prisoner for the duration of the First World War. During his internment he became interested in the Theory of Relativity, as written by Albert Einstein, and started translating various German physics books into English.

After the war, Brose undertook research and a PhD in England, where he helped promote Einstein’s theories during a time when there was still suspicion of German scientists. His translations eventually became the de facto English-language guides to this exciting new avenue of physics.

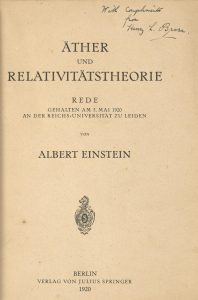

Copy of Albert Einstein’s ‘Äther und Relativitätstheorie’, 1920, with a handwritten dedication by Henry Brose. (Special Collection, QC6.1 EIN 6001874516)

The Preparation

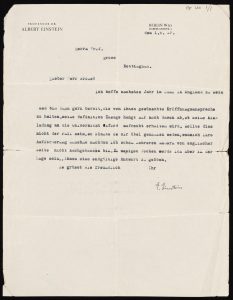

Brose was keen to get Einstein to come to England to deliver a lecture at University College Nottingham. We have Einstein’s reply, a typed letter on personalised notepaper dated 1 September 1927 (Gr Ue 1), where he agrees to give the lecture, but only if a simultaneous visit to Oxford University also goes ahead.

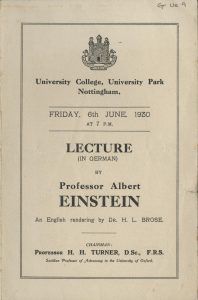

Ultimately, it would be a few more years before energy and mass coalesced to allow Einstein to travel to Nottingham. The lecture was scheduled for Friday 6 June 1930 at 7pm in the Trent Building’s Great Hall. We hold copies of the leaflet used to promote the event, which describes Albert Einstein as “the most famous living scientist” who “will rank in the history of science with Archimedes and Newton” (Gr Ue 9).

Pamphlet advertising a lecture given by Albert Einstein on 6 June 1930 at University College, Nottingham. (Gr Ue 9)

Pamphlet advertising a lecture given by Albert Einstein on 6 June 1930 at University College, Nottingham. (Gr Ue 9)

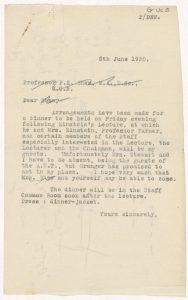

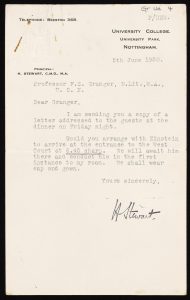

At the University there was much preparation for the event. The Principal, Hugh Stewart, organised a dinner in the Staff Common Room to follow the lecture, with instructions in a letter to guests to dress in dinner jackets (Gr Ue 5).

Letter from Principal Hugh Stewart to Professor Shaw concerning arrangements for Albert Einstein’s visit to University College Nottingham, 1930. (Gr Ue 5)

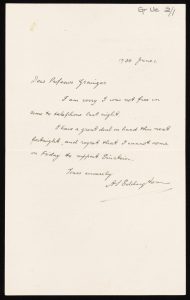

Another notable mathematician and astrophysicist, Arthur Eddington, was invited to attend Einstein’s lecture, though wrote back to express his regret at being too busy to attend (Gr Ue 2/1).

Letter from Arthur Eddington to F. S. Granger, 1 June 1930. Explains that he will be unable to attend Einstein’s lecture in Nottingham as he has “a great deal on hand this next fortnight”. (Gr Ue 2/1)

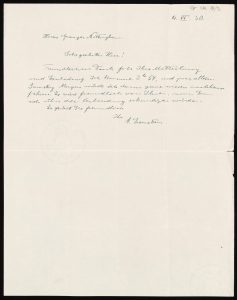

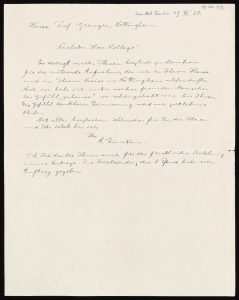

Einstein was offered accommodation in the home of Professor Frank Granger, Vice-Principal, which he gratefully accepted. In the same hand-written note to “Herr Granger”, Einstein noted that he would be arriving at 3.45pm on the Friday, “completely alone”, and asked if arrangements could be made for his travel home the following morning (Gr Ue 3).

Letter from Albert Einstein, to F. S. Granger, Nottingham, 4 June 1930. Handwritten letter dated 4 June 1930 expressing his thanks for the invitation to stay at Granger’s home whilst in Nottingham and outlining his travel arrangements. (Gr Ue 3/2)

Professor Granger was instructed to wear cap and gown, and ensure that Einstein arrived at the Trent Building at 6.45pm, where he would be met by Principal Hugh Stewart for a brief meeting before the lecture (Gr Ue 4).

Letter from Hugh Stewart, to Professor F. S. Granger, dated 5 June 1930, concerning arrangements for the visit and lecture by Albert Einstein. (Gr Ue 4)

The Arrival

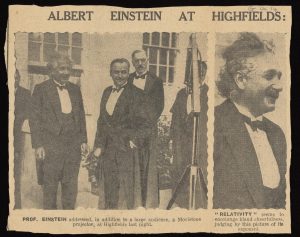

On his way to Nottingham, Professor Einstein visited Woolsthorpe, near Grantham, the birthplace of Isaac Newton, which is possibly why he arrived at Professor Granger’s house at 6.30pm, almost three hours later than planned. Accompanied by Professors Brose and Granger, he was brought by car to the Trent Building at University College Nottingham where he was greeted by Hugh Stewart, Alderman Edmund Huntsman, and other notable members of the University, including Henry Piaggio, Professor of Mathematics. Photographs were taken by the assembled media.

Photograph showing Albert Einstein outside the Trent Building, University College Nottingham, on 6 June 1930. To the right is Principal Stewart, with Professor Piaggio on the left. On the far left is Professor Turner, from Oxford University. (UMP 11/1/4)

Newspaper cutting from the Nottingham Guardian entitled “Professor Einstein’s Visit to Nottingham University College”, 7 June 1930. (Gr Ue 10)

Newspaper cutting, ‘Albert Einstein at Highfields’, 1930, likely from Nottingham Journal or Nottingham Guardian. (Gr Ue 14)

The Lecture

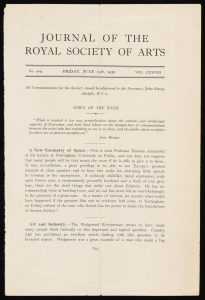

In the Great Hall Einstein was introduced by Professor Herbert Turner from Oxford University, who described him as “the greatest scientific man of our time”. He was given a “magnificent reception” by the attending staff and students. Einstein spoke into the microphone with a “curious childlike, timid expression”, according to the Journal of the Royal Society of Arts (Gr Ue 15), who said that although he did not have a “commanding voice”, he still gave the audience the impression of being “in the presence of a great man”.

Article about Einstein’s lecture at University College Nottingham from the Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 13 June 1930. (Gr Ue 15)

Article about Einstein’s lecture at University College Nottingham from the Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 13 June 1930. (Gr Ue 15)

In his lecture Einstein spoke on his developments on the theory of relativity, comparing elements by space and direction rather than matter. “Although my theory is not quite yet finished,” he said, “I have evidence, as far as I can judge, that the end is very near”. Speaking in German, Einstein was translated into English by his old friend, Henry Brose. Granger, in his written description of Einstein’s visit, noted that Brose’s translation was “wonderfully accurate”.

Despite being mentioned as forthcoming by student magazine The Gong, it does not appear that a full transcript of the lecture was ever published.

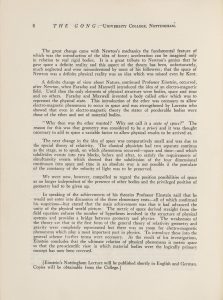

Article about the lecture given by Albert Einstein published in University College Nottingham magazine ‘The Gong’, Summer Term 1930, p.7-8. (UONC Periodicals Not 5.G14.8.E95)

Article about the lecture given by Albert Einstein published in University College Nottingham magazine ‘The Gong’, Summer Term 1930, p.7-8. (UONC Periodicals Not 5.G14.8.E95)

Newspaper cutting entitled ‘Prof. Einstein Propounds New Space Theories’, 1930, likely from Nottingham Journal or Nottingham Guardian. (Gr Ue 11)

Newspaper article entitled ‘Prof. Einstein on Relativity’, 1930, likely from the Daily Mail. (Gr Ue 12)

After the Lecture

The memories typed up by Frank Granger (Gr Ue 16/1-4) give a more intimate portrait of Einstein. Granger mentions that after the lecture, Einstein was taken for drinks in the Council Room (where he declined a cocktail) and then for dinner in the Staff Room. At 10.45pm Granger and his wife drove Einstein to their house, where he retired straight away to his room.

The next morning Einstein breakfasted with the Granger family, having coffee, bacon and eggs. With lit pipes they discussed many things, including the difference in political and religious freedoms between Germany and England. Taking a walk in the garden, Einstein spoke of his love of Bach and Mozart, but his dislike for the “passion” of Beethoven. Granger picked a forget-me-not and offered it to Einstein, who held it for the rest of the morning. Granger was insecure about his German, and felt he was missing some nuances of humour in Einstein’s speech. On the topic of language, Einstein was sceptical that Esperanto would ever become commonplace, but admired the simplicity of English.

- Typescript notes by Professor Frank S. Granger concerning Albert Einstein’s visit. (Gr Ue 16/1-4)

Retiring to his drawing room, Granger asked Einstein to write in his 1713 copy of Isaac Newton’s “‘Philosophiæ naturalis principia mathematica”. On the flyleaf Einstein inscribed

Mit diesem Werk Newton’s war das Vertrauen der Menschen in die Begreiflichkeit des Naturgeschehens gewonnen. Dies begrundet seine Unverganglichkeit.

which Granger translated as, “With this work of Newton, the confidence of mankind in the conceivability (rational apprehension) of the course of nature, was won. This establishes its imperishable character.”

Inscription by Albert Einstein in ‘Philosophiæ naturalis principia mathematica’ by Isaac Newton, 1713. (Special Collection, QA803.N6 SC171959)

Inscription by Albert Einstein in ‘Philosophiæ naturalis principia mathematica’ by Isaac Newton, 1713. (Special Collection, QA803.N6 SC171959)

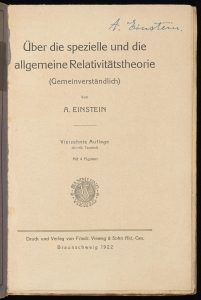

Granger also asked him to autograph published versions of Einstein’s own lectures. He donated the books to the University, and they are now part of our Special Collection.

Signed title page of ‘Über die spezielle und die allgemeine Relativitätstheorie (gemeinverständlich)’ by Albert Einstein, 1922. (Special Collection, QC6.1 EIN 6001874525)

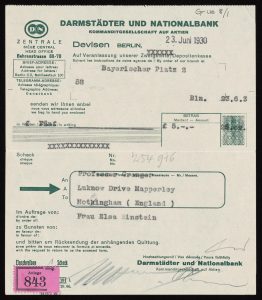

The Five Pounds

Once Einstein had returned home to Berlin he wrote Frank Granger a handwritten letter thanking him and his colleagues for the “touching reception” he received whilst in Nottingham, expressing his gratitude for the “princely sum” he received for the lecture, and that he was making arrangements for the return of the £5 lent to him during his stay (Gr Ue 6/2).

Letter from Albert Einstein, Berlin, to F. S. Granger, Nottingham, 1930. Handwritten letter in German dated 19 June 1930. (Gr Ue 6/2)

Sadly, Frank Granger’s typed up memories do not reveal the circumstances around why he lent Einstein £5. Yet among his papers we do have the correspondence from Einstein’s wife, Ilsa, promising the reimbursement of the £5, and receipt of the cheque itself (Gr Ue 7-8).

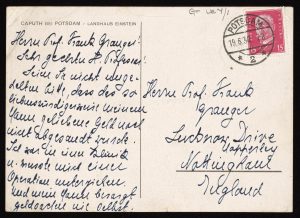

Postcard from Ilsa Einstein to F. S. Granger, postmarked 19 June 1930 explaining that there has been a delay in returning the £5 because she underwent an operation and Einstein never deals with financial transactions. The front of the postcard has a photograph of the Einsteins’ country house at Caputh near Potsdam. (Gr Ue 7/1)

Postcard from Ilsa Einstein to F. S. Granger, postmarked 19 June 1930 explaining that there has been a delay in returning the £5 because she underwent an operation and Einstein never deals with financial transactions. The front of the postcard has a photograph of the Einsteins’ country house at Caputh near Potsdam. (Gr Ue 7/1)

Frank Granger wrote about Einstein’s visit for the Nottingham Journal, making note that Einstein’s health meant that he had to cancel a visit to Oxford University to receive an honorary degree. A future visit to Nottingham was touted by Brose in 1931, and again reported in the local newspaper, though never happened.

Newspaper article from the Nottingham Journal reporting Einstein’s visit to Nottingham and his opinion of the work of Isaac Newton and George Green, 30 June 1930. (Gr Ue 13)

Newspaper article ‘Prof. Einstein Again for Nottingham?’ from the Nottingham Journal, 27 June 1931. (UR 1438, p.106)

The Return of (Half) the Chalk

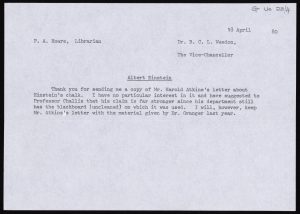

In 1980 the Fleet Street journalist Harold Atkins wrote a letter to the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Nottingham asking if they, for the 50th anniversary of Einstein’s lecture, would like to receive part of the chalk Einstein had used during the lecture (Gr Ue 23).

Atkins, who at the time was a young science correspondent at the Nottingham Journal, was given a ticket to the lecture by his old schoolfriend, Charles Edlin, who was studying Physics at University College Nottingham under Henry Brose. Edlin was sat near the front, and once the lecture was over, ran up and grabbed the piece of chalk Einstein had been using to draw equations on the blackboard. Snapping the chalk in two, he gave one half to Atkins, who had preserved it ever since.

Although originally offered to the University archive, the then head of the Library decided the chalk would be better in the possession of the Physics and Astronomy Department, custodians of the blackboard.

Memo dated 18 April 1980 from P.A. Hoare, Librarian at the University of Nottingham, to Dr B.C.L. Weedon, the Vice-Chancellor, regarding the offer of the return of part of a piece of chalk used by Albert Einstein. (Gr Ue 23/4)

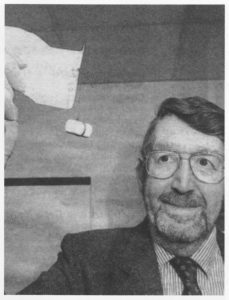

Professor Lawrie Challis of the Physics Department holding a piece of chalk used by Albert Einstein, c.1980. (Source unknown; reproduced from ‘Nottingham: a History of Britain’s Global University’ by John Beckett, p.85.)

The material featured in this blog is available to view upon request in Manuscripts and Special Collection’s Reading Room at King’s Meadow Campus. Please email us for more information: mss-library@nottingham.ac.uk

Members of the public are welcome to view Einstein’s blackboard in the Physics and Astronomy Department, by appointment only. Please email them in advance of visiting:

pp-reception@exmail.nottingham.ac.uk

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply