May 9, 2024, by Chloe

A Painter and A Petition

In late 1841, Henry Pelham-Clinton, 4th Duke of Newcastle, received an unusual request in the post, comprising of a letter and petition from a man named as Thomas J. Williams asking for financial support to attend the Royal Academy in London, in order to hone his talents as a painter.

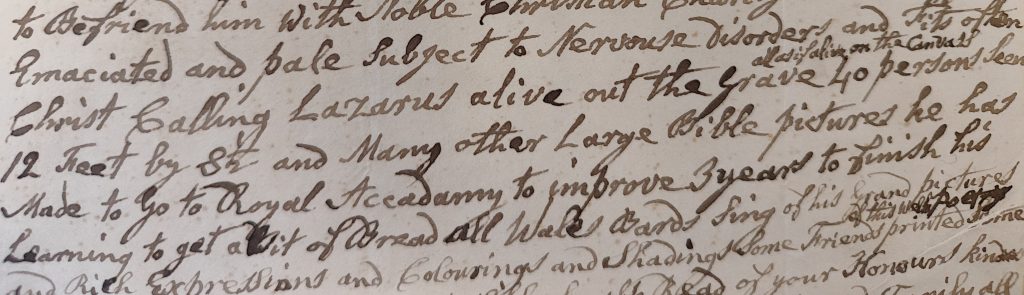

In the petition, which is addressed ‘To all Charitable and well disposed Persons’, Williams introduces himself as the nineteen year-old son of the Harbour Master at Carnarvon [Caernarfon] stating ‘That your Petitioner is Deaf who Drew and painted the Drawings herewith exhibited, and that he never was taught or instructed by any Person whatever’. He goes on to confirm that his parents do not have sufficient funds to pay for his instruction themselves, and that he is requesting only a ‘small sum’ to support his studies. Below this statement lies a list of benefactors, ranging from the Lord Bishop of Bangor to Col. Douglas-Pennant, the MP for Caernarvonshire, making donations of between £1 and £6.

![Text reading: The Right Hon[ourable] Lord Bishop of Bangor; The Rev[erend] W J Cotton, Dean of Bangor, £2; Richard Garner Esquire, £2; Ric[hard] Thomas Esquire, £2; Mrs Hunt Glamg[wnna?], £1; Men[a?] [F?]ion Anglesea, £1; Rowland Jones Esquire, Broom Hall, £1](https://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscripts/files/2024/05/Ne-C-7326-1-bottom-1024x416.jpg)

Ne C 7326/1, Extract from Petition ‘to all charitable and well disposed persons’ by Thomas J. Williams, sent to Henry Pelham-Clinton, 4th Duke of Newcastle under Lyne; 13 Oct. 1841

This goes some way towards shedding light as to why a young man from North Wales would address his appeal at an aristocrat from the English Midlands, considering the lack of an obvious connection between them – if this letter was simply one of many directed at ‘Charitable and well disposed persons’ then the choice of potential benefactor is less critical; and besides, while many of the donors do have local links, many are also part of the same political circles as Newcastle, perhaps providing the pretext for the request.

Ne C 7326/2, Letter from Catherine Williams, Carnarvon, Carnarvonshire, to Henry Pelham-Clinton, 4th Duke of Newcastle under Lyne; n.d. [c. 13 Oct. 1841]

The petition was also accompanied by a supporting letter from his mother Catherine, which, unlike the first document, is explicitly addressed to the ‘Most Noble Duke of Newcastle’, and takes a two-pronged approach to advocating for her son’s education, emphasising that he is a ‘sickly youth…subject to nervous disorders and fits’, before going on to describe the widespread praise his work has received, claiming that ‘all Wales bards sing of his Grand pictures’.

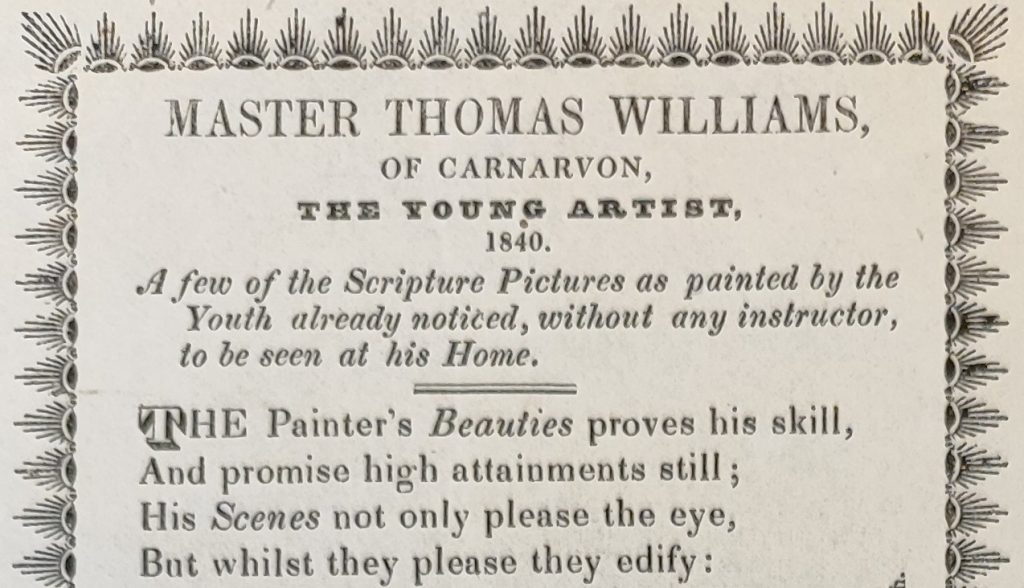

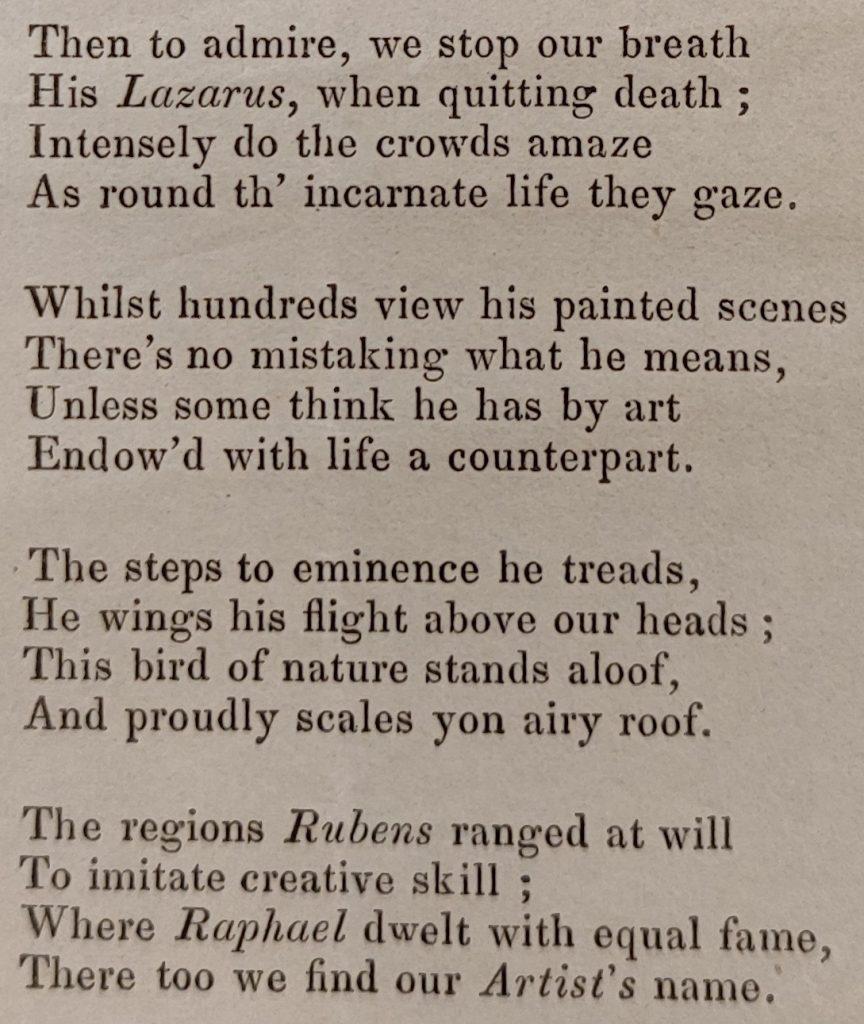

And sure enough, the appeal came furnished with printed copies of two poems in praise of William’s work. The first, an English translation of a Welsh original, describes in rapturous terms his many paintings on religious subjects: positioning them at the vanguard of a moral crusade which seeks to ‘edify’ the viewer. Indeed, the poem goes so far as to liken the experience of viewing his work to that of hearing a sermon, and to pray for an artistic education that will enable Williams to ‘teach the youths of his Native Wales’ – in matters of faith as much as in painting, it might be inferred.

The second work takes a wider lens, seeking to establish the extent of his dominion – both on the canvas, establishing his mastery of both the panoramic and the intimate, and within the artistic canon, placing him alongside the likes of Rubens and Raphael. It is perhaps no coincidence, then, that the Welsh and English versions of the text lie side by side: the fame of his works unconstrained by either language or landscape.

In light of all this hyperbole, it might strike the reader as surprising that there is no known record of a reply by Newcastle, or indeed of whether or not Williams ever received an artistic education. More disappointingly, considering the hundreds of words – not to mention the substantial donations – spent on their praise, there are no surviving works attributed to him.

It seems, then, that we will never ‘stop our breath’ to see his Lazarus ‘quitting death’ – but we may yet console ourselves that his works remain, ‘as if alive on the canvas’, at least in the words of his many ardent supporters. Discover his story for yourself in our Reading Room – to find out more, or to book an appointment today, please contact us at mss-library@nottingham.ac.uk.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply