December 21, 2023, by Chloe

Bloody Flux and the King’s Evil

This is a guest post by Jayne Muir, who volunteered at Manuscripts and Special Collections between April and September 2023, cataloguing medicinal herbs and their uses in remedies from material held in our collections.

The byways, meadows and cottage gardens of Britain were once a vast larder of ingredients from which oils, ointments, tinctures, pills, poultices and reviving drinks were concocted to treat all sorts of illnesses and ailments. Although modern drugs rely more on the laboratory than the hedgerow, the healing properties of many plant and herb extracts have been scientifically proven: digitalis from foxgloves to treat some heart conditions; extracts from yew trees in the manufacture of chemotherapy drugs and aspirin from the bark of certain willow and birch trees.

Traditional remedies were passed from one person to another and some were written down in books, often alongside culinary recipes or religious texts. The University of Nottingham Manuscripts and Special Collections holds examples of such books, and in conjunction with the recent Plants and Prayers exhibition at the Weston Gallery, volunteers have been researching the cures and recording their ingredients to help with future research. Some of the remedies are simple, others are more complex and many are surprising.

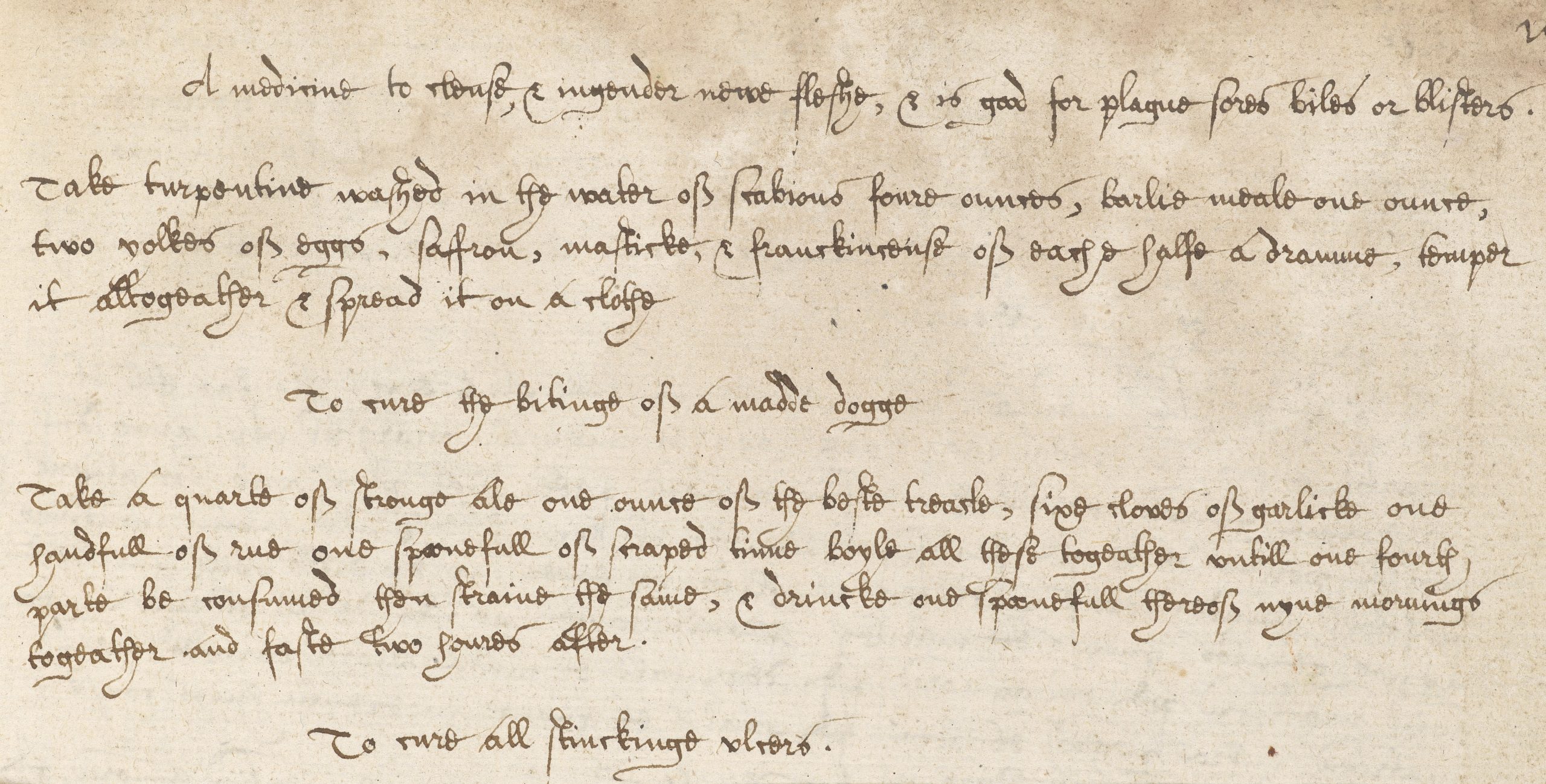

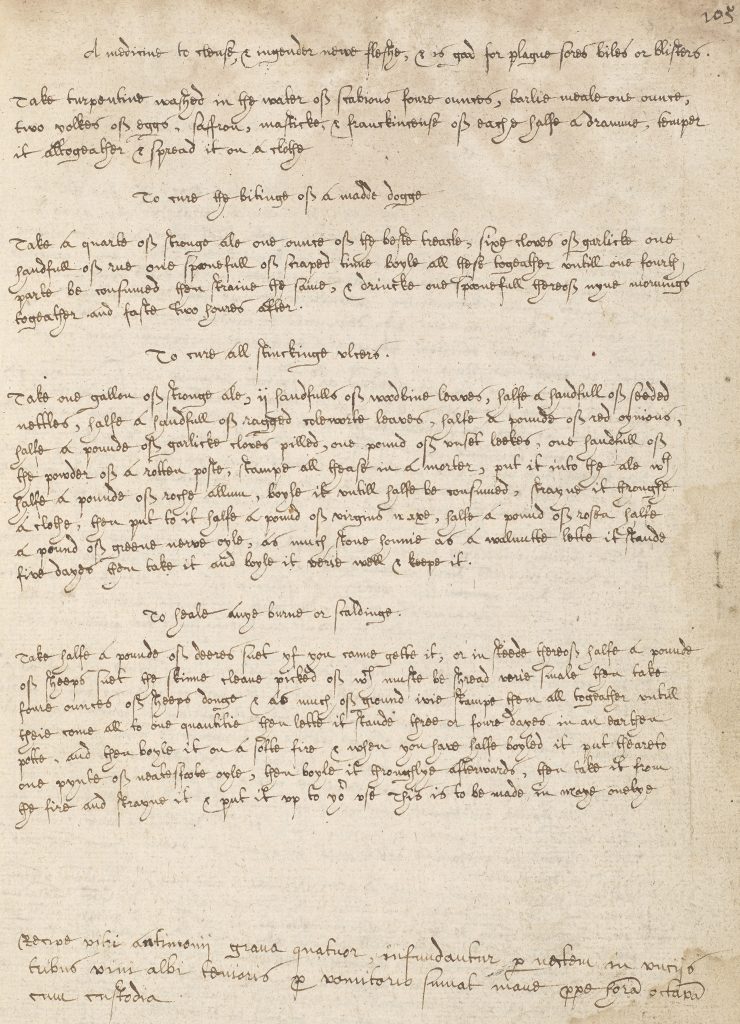

Recipe for Mad Dog Bite from precedent book containing documents dating 1590s to 1620s with personal notes by John Tibberd from the 1620s, AN/P 283.

According to the Archdeaconry of Nottingham Precedent Book (AN/P 283) someone with toothache in the 17th century might have been advised to apply a combination of hyssop and vinegar, whilst for ‘teeth that are black or stink’ the mixture was frankincense, sage and salt. Grease of a fox plus mustard and vinegar might help the cramps and wild tansy could staunch the blood. According to Margaret Willoughby’s 18th century household book (MS 97/3), weak eyes could be treated with a mix that included rosemary, eyebright, betony flowers and clove bark, ground to a powder, mixed with tobacco and smoked. To ease toothache the juice of a roasted onion should be dropped ‘into the ear’. For leg sores, ‘let the patient stand in spring water’ before applying a plaster of sorrel and egg white to the affected limbs.

Remedies for more serious complaints such as the king’s evil (scrofula, a type of tuberculosis) also feature. One 18th century cure required ragwort and hogs’ grease. Another consisted of wax, turpentine, sheep’s tallow, barley meal and the ‘urine of a man child not above 3 years’. The ingredients for a purgative to treat the bloody flux (dysentery) included rhubarb, cinnamon, opium and clarified honey. Treatments or preventions for the pestilence (probably bubonic plague) appear quite frequently and range from a simple mix of lily root and white wine in the 17th century example, to a concoction of 40 different plants mixed with strong ale and best brandy in an 18th century recipe.

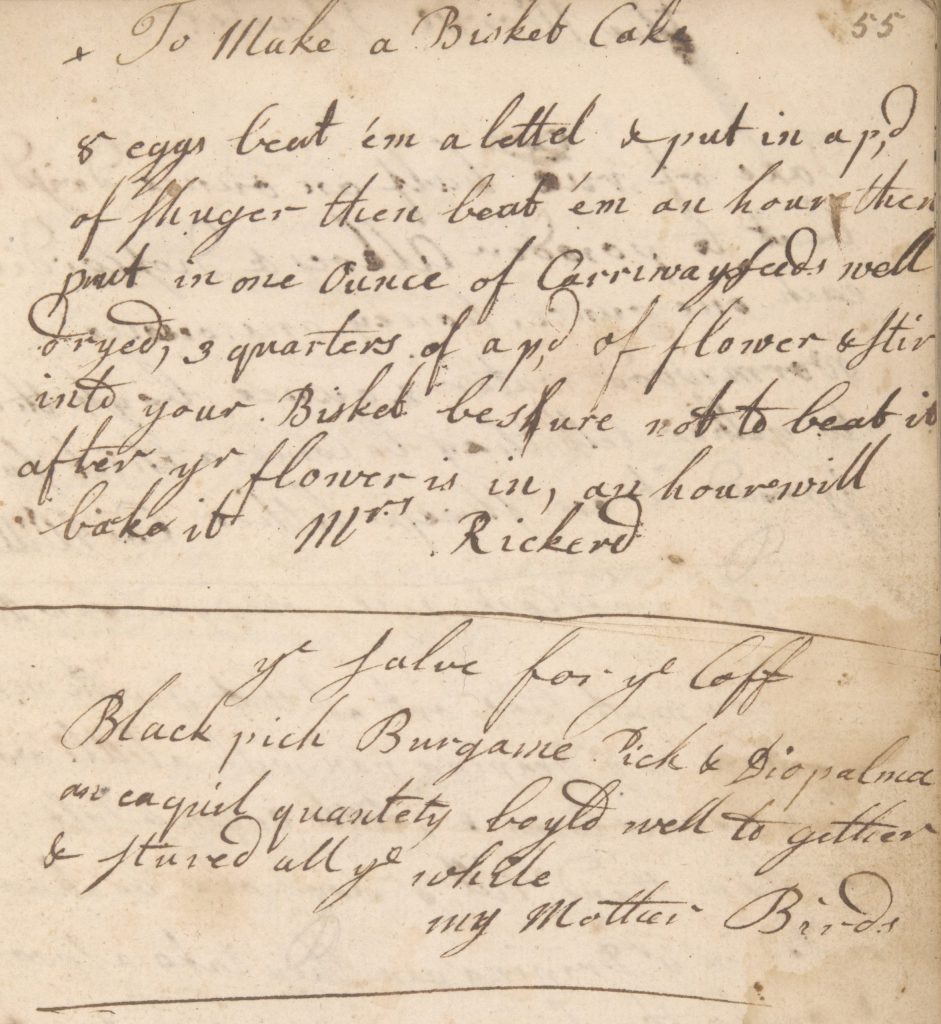

Page 55 from ‘Mrs Willoughby’s Household book’ (MS 87/4) showing a recipe for a ‘bisket cake’ and for a salve for a cough. The latter recipe is attributed to ‘Mother Bird’.

Some of the remedies are noted as ‘proved’ or ‘approved’ or include further apparent evidence of their usefulness, such as a gout prevention consisting of oil of honey and balsam, which ‘helped an ambassador in Rome and he was never troubled with the pain any more’.

Some of these cures may well have helped, others we know were ineffective, but books like these give an insight into the illnesses and conditions that concerned earlier societies, as well the native plants at their disposal and the more exotic ingredients imported to Britain. A mix of strong ale, garlic, rue and scraped tin might have been used to treat the bite of a mad dog in the 17th century, but a shot of tetanus is probably more advisable today.

As part of this project, over 3400 records have been created which cover approximately 200 years from the early 1600s to the late 1700s. The research can be accessed in our Reading Room – to find out more, or to book an appointment today, please contact us at mss-library@nottingham.ac.uk.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply