September 30, 2021, by Kathryn Steenson

Absolute Units

There’s been talk in the news about reintroducing imperial units, and we here in the archives love nothing more than the chance to show off our knowledge of the archaic and obsolete. In this case, systems of measuring stuff.

Imperial units have been used in Britain since the Roman era – the ‘imperial’ refers to the Roman Empire – alongside various other overlapping and contradictory (but sometimes similarly-named) systems that varied by region, time, trade, and the thing being measured. Their use wasn’t standardised until Weights and Measures Act came into effect in 1826. That being said, Britain has been officially metric for decades now, but back when buying beer in a pub and petrol was possible, we still thought about it in imperial units of pints, gallons and miles. It’s unlikely that the older units were abandoned immediately the Act came into force.

They would walk 500 miles just to be the legion who brought imperial units to your door

The standard linear measure in the Imperial system is the mile, which was based on a Roman measurement of 1,000 paces. We’re also familiar with the unit of a foot, which was traditionally held to be the length of a man’s foot. If you’re an Army on the march, then both of those make sense.

If a ‘foot’ is based on the measurement of a man’s foot, then surely British shoe sizes must be anatomically-based too? The length of a toe or something? Oh no. No, it is of course the barleycorn, from an actual ear of barley. A size 12 shoe is 12 inches, and each preceding size in one barleycorn (1/3 inch) smaller.

Grain is going to feature later on as a standard by which we measure things, but let us return to walking distances for a moment, starting with the furlong, ‘a furrow long’. It’s the distance that could be ploughed by an ox without a rest. For those of you without an ox handy to check, it’s about 1/8 of a mile or 220 feet.

Q: What connects historians, archivists, and railway workers?

A: Chains!

For those of you who sadly don’t get the many and amusing layers of that pun, chains were the literal length of a surveyor’s chain (66 feet in England, but not in Scotland) and so it crops (ahem) up in a lot of land records. Structures like bridges along older railways lines are still are still given a location based on miles and chains.

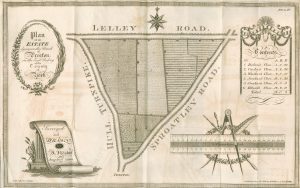

Plan of an estate lying in the parish of Preston in the East Riding of the County of York. Surveyed and drawn by A. Nesbit, August, 1808.’ Ref: 1004300304

This map has a scale in chains, and let’s appreciate the fact that Mr Nesbitt spent considerably longer on the illustration of this map than the practical measuring, before we look at the content. The tenants’ land is given in A[cres], R[ods] and P[erches], and if you are expecting to be given a nice simple conversion to feet or something, well then you’re very much in the wrong blog post.

There were a wide variety of traditional measurements of land used into the seventeenth century, based on what the land produced rather than size, which varied wildly depending on the quality of the soil and the climate.

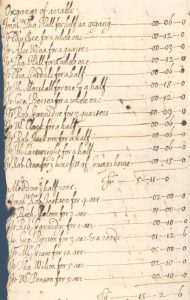

In this 1642 rental for Cromwell, you can see the ploughed arable land at the top measured in oxgangs, and the non-ploughed meadow land below in acres. An oxgang (or bovate) was the amount of land which could be ploughed using one ox, in a single annual season. We’re only looking at the different land measurements, we’re not touching the fact that geese were currency. Although there are probably a few people wishing they could send their landlords a flock of angry geese.

An Imperial acre was officially 1 furlong by 66 feet and it would have simplified the matter greatly if arable fields were all made up of long rectangular strips of land. Unfortunately land just doesn’t neatly divvy up like this, hence the need for areas like perches (30¼ square yards) and roods (40 perches).

Finding Your Weigh

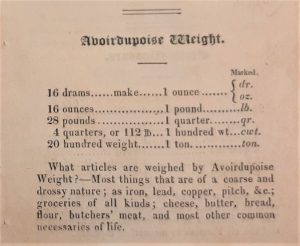

The Romans were not the only people to bring their systems of weights to Britain: the Normans brought Avoidupois (literally avoir du pois, goods by weight) to measure large and bulky items. It became the most common weight measurement, and is still used by people to measure their weight in stones, pounds, and ounces (not to imply any of our delightful readers are large and bulky).

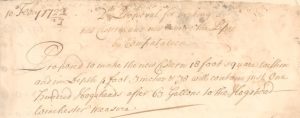

In this 1723 proposal to make a cistern, it is stated that ‘To make the Cistern will take in Lead Besides Lapps and Flashes at 10lb to the Foot 2 Ton 16 Hund. 1 Quartr 14 lb’.

Accounted proposal for making a new cistern and for pipe-laying, sent Lord Edward Harley, 10 Feb 1722/3. Ref: Pl C 1/389

There being 16 ounces to the pound, 14 pounds to the stone, two stone to the quarter. Guess how many pounds to the hundredweight? Guess.

It’s 112. But of course (and, historians, you do not get to cast the first stone here, with your 116-year “Hundred” Years War).

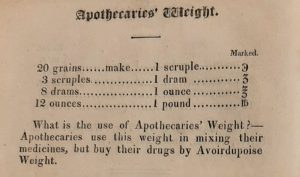

If all this maths is giving you a headache then you’ll need a small dose of something from the apothecary. Luckily the Apothecaries’ weights have the same base unit as Avoirdupois: the grain, the weight of a grain from the middle of an ear of barely. Unfortunately it diverges from there. There are fewer grains in an Apothecaries ounce than an Avoirdupois ounce, and there are only 12 of them to a pound. If you weren’t aware of this it would probably cause confusion trying to recreate recipes from our medical treatment books, except that doctors’ handwriting was an appallingly illegible scrawl even back in the 18th century.

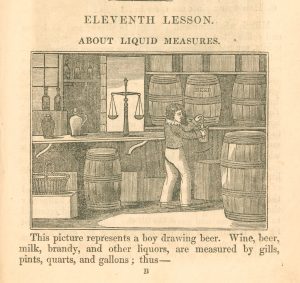

These pages are from An Explanation of the fundamental rules of arithmetic, 1822 (Ref: Briggs Collection, LT 210.QA/E9) designed to explain the various different systems in use.

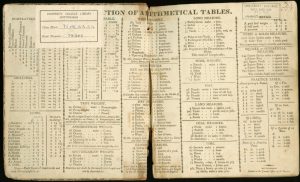

Such publications were common. This ‘Collection of Arithmetical Tables’ is taken from a memoranda book (MS 99) for a sheep farm in Nottinghamshire printed in the early 19th century, because nobody was expected to be able to remember and convert them.

But what’s this with the wool measurements? Cloves, wey and sacks, also known as bags? It turns out that the nursery rhyme baa baa black sheep, have you any wool? Yes sir, yes sir, three bags full wasn’t just referring any old bag of wool, but an actual specific volume of wool.

The new Leicester breed, ram, from Low, David, ‘The breeds of the domestic animals of the British Islands’. A 2-shear sheep whose wool is sold by sacks, apparently.

Good for what ales you

The last two words on the account for the pipe-laying pictured above are ‘Winchester Measurement’. This is because the gallons referred to are being measured in the dry gallon, traditionally used to measure corn, salt, peas and other similar goods. A gallon was quite a small measurement of dry goods: a peck (as in the quantity of pickled peppers Peter Piper picked) is two gallons, and a bushel was 4 pecks. But here, the tradesman has decided to use dry gallons to measure water, despite there being several wet gallon volumes available to choose from.

The dry gallon is larger than the wine gallon and smaller than the ale gallon, and they’re all different from the Imperial gallon that replaced them in the 1820s.

Are you being driven to drink yet? We anticipated this so we’ve ordered in a hogshead of ale and a pipe of wine. How much is that in Imperial gallons? Well, I’m afraid that depends if it’s an imported wine, which uses a different system…..

Contest time: finish this sentence from ‘The Child’s Arithmetic: A Manual of Instruction for the Nursery and Infant Schools’, 1837.

If you’d like to delve more deeply into measurements – and this is not a recommendation – then we have an Introduction to Weights and Measurements on our website. You can also read our magazine Discover and follow us on Twitter @mssUniNott and instagram @mssUniNott.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply