May 8, 2020, by Kathryn Steenson

Victory in Europe Day

Today is Victory in Europe Day, marking the 75th anniversary of Nazi Germany’s unconditional surrender to the Allies in World War II. Adolf Hitler had committed suicide on 30 April once it became clear that Germany’s military forces were on the brink of collapse. He was succeeded by Karl Dönitz, formerly the Supreme Commander of the Navy, and it was Dönitz who authorised Germany’s surrender.

A preliminary surrender was signed on the 7th May, too late for newspaper front pages, but the news spread rapidly that the war would soon be over. By the 8th the excitement had reached fever pitch. It’s estimated that more than a million people took to the streets to celebrate the end of the European part of the war (the war with Japan continued until August). King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, accompanied by Prime Minister Winston Churchill, addressed the crowds from the balcony of Buckingham Palace.

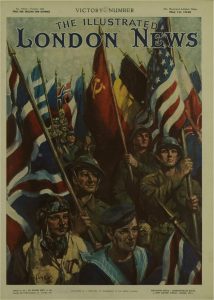

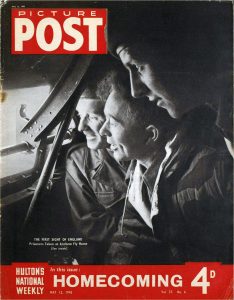

The Library has subscriptions to the archives of the daily newspapers The Times, Telegraph, Guardian and Daily Mail, as well as the weeklies London Illustrated News and Picture Post, if you’re interested in how VE Day was reported (institutional log-in required).

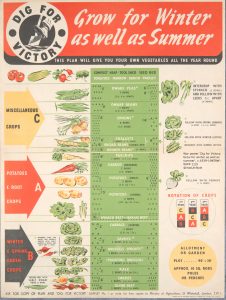

Life on the Home Front had not been easy during the six year war – we’ve previously blogged about the ‘Nottingham Blitz‘, the bombing raid in May 1941 that killed 150 people. Nottingham was targeted because of its industrial sites and factories, but the city escaped the worst of the bombing raids in England. More photos of the damage caused during the raid are online in our ‘University College at War’ gallery, along with photos of the University participating in the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign, where swathes of University Park Campus were ploughed up and planted.

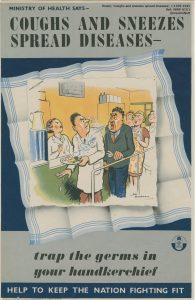

Slogans like ‘Dig for Victory’ and ‘Make-do and Mend’ are still familiar today, and have their origins in posters that used colourful images and simple slogans to encourage people to contribute to the war effort. The ‘Coughs and Sneezes Spread Diseases’ poster is currently very topical, and it was produced for similar reasons as the Government’s current handwashing guidance: keeping the population healthy so as not to overwhelm medical facilities, but also to keep key workers literally fighting fit. Posters about growing fruit and vegetables sometimes lead people to assume that the population was more self-sufficient than it actually was. In truth, Britain relied heavily on food imports that became more difficult and dangerous once war was declared. Information posters like the one above were needed because many people (especially in cities) didn’t have much experience growing veg.

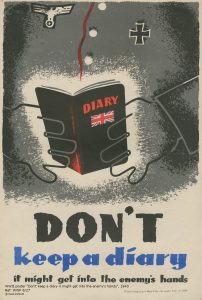

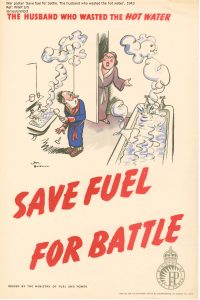

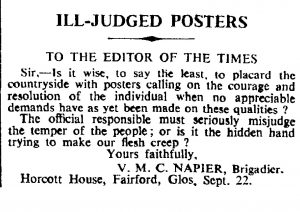

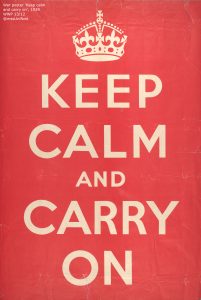

The Ministries of Agriculture and Health were not alone in producing posters: numerous departments within the British government used them as a ways to provide information – and motivation – to the general public, including the Ministry of Fuel and Power, the Ministry of Information, and the Board of Trade. The posters covered many aspects of domestic life, and were displayed in public places across Britain as reminders that individual small acts could collectively contribute to the war effort. Some of the slogans, such as ‘Don’t Be Fuel-ish’, have faded into obscurity or no longer apply, such as ‘Don’t Keep A Diary’ (please do keep diaries, consider donating them to your local archive). Ironically, the most famous motivational poster of all, ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’, was never officially displayed. It was part of a set of three intended to strengthen morale in the event of a wartime disaster along the lines of invasion or major bombing. Just under 2.5 million were printed but the campaign was criticised for being patronising and costly, and the majority of posters were pulped, which is why the slogan did not enter everyday language until the poster was ‘rediscovered’ (i.e. made commercially available) in 2000.

We have just over 300 British WWII posters, including the five shown here, which were formerly in the possession of Vivian de Sola Pinto, Professor of English at The University of Nottingham from 1938 to 1961. They were found in a case of Pinto’s papers that was donated to the University after his death. Many have been digitised and are available to view and download from our ‘Second World War Propaganda’ online gallery – by anyone, not just members of the University – and about 160 of the complementary set of Russian WWII posters that Professor Pinto also owned are available online on the ‘Windows on War’ project site. The University of Nottingham’s collection of Soviet war posters is unique in the UK, and is one of the largest internationally. It is interesting to note the very different styles of art and message used between the British and Soviet propaganda posters, but in both cases, the Governments urged their people to make sacrifices and help do their bit to ensure victory, even though they stayed at home and were not on the battlefield.

More information about the archives and rare books we hold in Manuscripts & Special Collections is on our website. You can also read our newsletter Discover and follow us on Twitter @mssUniNott. Currently the Reading Room is closed, but if you have a question or want copies of the documents shown here, get in touch at mss-library@nottingham.ac.uk and we’ll do our best to help.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply