April 13, 2020, by Kathryn Steenson

Heirs and Spares: Succeeding George IV

This is a guest post by Dr Richard A Gaunt, academic curator of the exhibition Georgian Delights: Life during the reign of George IV 1820-1830.

George IV spent most of his adult life waiting to be King. So accustomed have we become to this fact, and to the various machinations associated with his part in the Regency Crisis of 1788-89 (memorably immortalised in Alan Bennett’s The Madness of King George), that we have forgotten how vulnerable George’s own legacy was, once he succeeded to the throne in January 1820.

In Georgian Delights, the prominence of this issue was reflected in devoting the whole of the central exhibition case to the succession to the throne. Informally known as the ‘Heirs and Spares’ case, the content sought to chart the circumstances through which three putative heirs to the throne came into their inheritance and, in two cases, lost it.

The threat of a Catholic claimant to the throne had largely been extinguished with the repulse of the Jacobite Rising of 1745. Though there were still living descendants of the House of Stuart, at the time of George’s accession, the ruling Hanoverian dynasty had established itself in political fact and popular acclaim as the ‘legitimate’ ruling family of the United Kingdom. This had been reinforced in 1814, during the Regency, when the country commemorated the centenary of the accession of the House of Hanover. It is not surprising that, after being crowned as King, George spent much of the period 1821-22 progressing through his kingdoms – notably, Scotland, Ireland, and Hanover – as a public display of royalty.

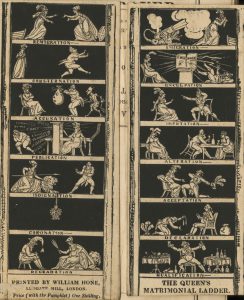

The Queen’s Matrimonial Ladder cardboard game by Hone, c.1827, depicting the stages of the marriage between [Queen] Caroline and King George IV. From Hone’s select popular political tracts.

Over the course of the next decade, George’s inheritance passed to his next two younger brothers: Frederick, Duke of York, and William, Duke of Clarence. Both had followed the conventional path of younger sons of the monarch, York by serving in the army (he rose to be commander in chief of the army) and Clarence by serving in the navy. Both took mistresses: Clarence conducted a long-term (and loving) relationship with the actress Dorothea Jordan, but the Duke of York consorted with a woman who nearly destroyed his reputation. Mary Anne Clarke was found to be involved in trading commissions in the army. York resigned over the scandal, in 1809, but was later re-instated as commander in chief, when Clarke’s friend, Gwillym Wardle, was discovered to be the principal actor behind the scenes. York recovered his reputation sufficiently to become the leading opponent of Catholic Emancipation in the 1820s. For Ultra-Tories worried at the threat of Catholics becoming MPs, York was the trump card in their opposition to the measure. However, York died in 1827, shortly before the final political crisis which resulted in Catholic Emancipation in 1829, and the succession passed to Clarence.

Public and private life of that celebrated actress, Miss Bland,otherwise Mrs. Ford or Mrs. Jordan, 1886. Ref: PN2598.J67 .P8

Clarence had already abandoned Mrs Jordan in less than honourable circumstances; she died in 1816. Following Princess Charlotte’s death, the government offered financial inducements to George’s brothers to contract marriages which would produce legitimate heirs. Clarence found a congenial wife in Princess Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen in 1818. The couple had children together but none of them survived childhood. Clarence was, in some respects, more liberal than both his older brothers. He succeeded to the throne in 1830. Although he was widely known as the ‘Sailor King’, his naval career had not been especially conspicuous, although he had avoided the fate of the ‘Grand Old Duke of York’ by being memorialised in a satirical nursery rhyme. Ruling as King William IV, Clarence went on to preside over a period of political and social reform which presented a sharp contrast with the reign of George IV. Lacking a legitimate heir of his own, the throne passed to his niece, Princess Victoria, when he died in 1837. The future of the monarchy, which had seemed so vulnerable in 1820, now looked far more secure.

A virtual version of the exhibition, including videos and copies of the exhibition boards, is available online.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply