March 13, 2020, by Kathryn Steenson

Off to the races!

As today is final day of the Cheltenham Races, we’re trotting out some documents about horse racing in Britain and how some of its notable figures crop up in our collections. It’s become a cliche that the feckless elder son of an aristocrat gambles away the family fortune on cards and horses, but although there is an element of truth in that, many of the wealthy enthusiasts regarded horse racing as a business and well as a recreational pursuit.

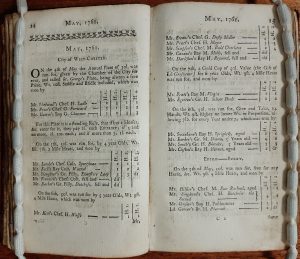

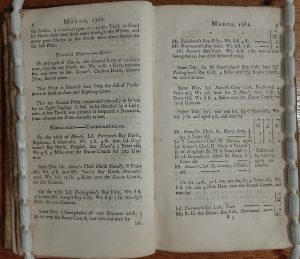

The concept of racing horses over a set distance to see which is fastest has been around for many thousands of years. In Britain, formal race meetings began in the sixteenth century, which is when the first evidence of trophies and official race courses appears. These pages are from ‘An historical list of horse-matches run; and of plates and prizes run for in Great-Britain and Ireland, in the year 1761’ by Reginald Heber, published in 1762 (Special Collection GV1018.5 HEB). It’s a comprehensive list, giving details of prizes, information about the horses and their owners, and reproducing text from relevant Acts of Parliament. By the time this volume was published in 1762, Chester had had a racecourse for over 200 years (and is the oldest race course still in use) and Newmarket, though arguably more important, had had a race course for almost 130 years. Oddly, this volume also contains a small chapter dedicated to cockfighting. Similar lists of horse races – minus the cockfighting – had been regularly published since 1727 and indicate a widespread interest in the sport.

William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne (1593-1676) was an athlete, scholar, and eventual owner of Nottingham Castle. Particularly famed for his horsemanship, he wrote two significant works on the subject: ‘A new method, and extraordinary invention, to dress horses, and work them according to nature‘ (1667) [University log-in required] and ‘Méthode et invention nouvelle de dresser les chevaux‘ (1658). In 1633 and 1634 he entertained the king lavishly, first at Welbeck Abbey in Nottinghamshire and then at Bolsover Castle, where he had built a large indoor riding school. He was appointed governor to Prince Charles in 1638, teaching him horse riding. There are occasional references to his interest in horses within the Portland (Welbeck) Collection, which includes some of his personal papers.

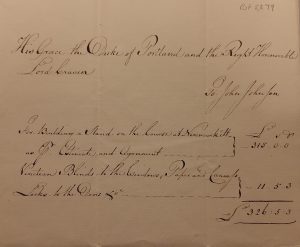

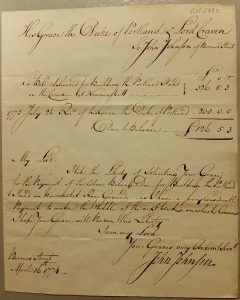

He was not the only Duke whose archives we keep to have a keen interest in horse racing. These documents show the costs the 3rd Duke of Portland, William Cavendish-Bentinck (1738-1809) incurred from ‘Building a Stand on the Course at Newmarkitt’. The total amount of £326 is around £28,000, according to The National Archives money converter, and includes £11 for Venetian blinds, wallpaper and locks. Portland had paid most of the balance, but John Johnson, who was overseeing the project, wrote in April 1774 asking for the outstanding amount to be paid as he had a considerable payment to make in the middle of next week.

Pw F 5879: Bill from John Johnson to [W.H.C. Cavendish-Bentinck], 3rd Duke of Portland and Lord Craven (1773)

Pw F 5880: Letter from John Johnson, Berners Street [London], to [W.H.C. Cavendish-Bentinck], 3rd Duke of Portland, Burlington House [London] (16 April 1774)

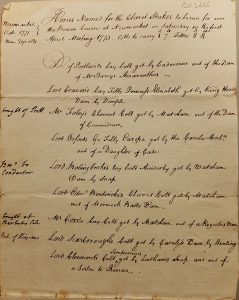

Horse racing was a family interest: the Lord Edward Bentinck with the chestnut colt listed here is his younger brother. The Jockey Club governed the sport until its governance role was handed to the British Horseracing Board, and there are several letters within the collection to and about the Jockey Club, sometimes grumbling about their decisions, sometimes discussing the Club’s finances, and a few discussing the legal cases the Club was occasionally involved in – including a dispute between two gamblers over payment of a debt, which the 4th Duke of Portland (another William!) weighed in on.

Pw F 3655: List of horses ‘named for the Claret Stakes to be run for over the Beacon Course at Newmarket on Saturday in the first April Meeting 1773’; provides a comment about each horse and states the owner. Sent by William Fenwick to [W.H. Cavendish-Bentinck], 3rd Duke of Portland; n.d. [c. Oct. 1771].

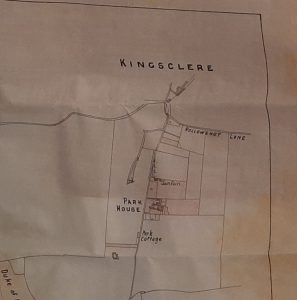

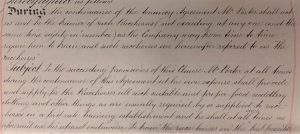

And finally, there are these documents from the twentieth century, continuing 400 years’ of the Dukes of Portland being involved with horse racing (both from Pl F10/3: Bundles of material relating to The Kingsclere Racing Stables, Ltd; 1903-1920). Better known to some as the setting for Richard Adam’s novel ‘Watership Down’, Kingsclere and the surrounding area was also the home of Kingsclere Racing Stables, which trained many racehorses. The Duke of Portland was one of the investors, and this is a 1903 agreement to employ the famous John Porter (1838-1922) as a race horse trainer and tenant of Park House. Actually, this was to re-employ him, as he’d lived and worked there for many years, but the agreements were renewed annually In it, he agrees to train no more than 80 horses at any one time, and to provide at his own expense proper food, saddlery and anything else a ‘first rate training establishment’ required. Porter was described as “the most successful trainer of the Victorian era” but by 1903 he was in his sixties and would retire within a few years. A syndicate with Porter, Portland and several others was set up, but there seems to have been a falling-out. Portland wrote he wanted to hire a ‘younger and more energetic’ trainer, and Porter felt that he had been treated un-generously in view of all he had done, and this along with various other clashes and problems prompted both men to withdraw.

These documents are at Manuscripts & Special Collections. If you’d like to visit the Reading Room, to see them or the other archives and rare books here, please contact us to make an appointment. You can also follow us on Twitter @mssUniNott and read our newsletter Discover.

Dear Sirs,

Being a son of Nottingham, I have, for many years been a student of the lives of the Dukes of Portland.

Especially William.the Fourth Duke, and of his third son, Lord George Bentinck.

Another extremely interesting article, was that which referred to a section in The Racing Calendar of 1762, with regard to Cockfighting, and that there was no mention of it in the earlier editions.

I have in my collection, a copy of the fourth ever printed edition of 1731, as you rightly say, the first edition was printed in 1727. by John Cheny. The reason that I mention this is because it does include a chapter on Cockfighting.

Yours faithfully

John Share