February 23, 2019, by Kathryn Steenson

Spooky Scary Skeletons

Guest post by Anja Rohde, Library Assistant.

On Wednesday 27th January 1943 Nottingham students awoke to an unusual sight – a skeleton was suspended from the clock tower of the Trent Building. This was ‘Mrs Criker’, one of the mascots of Goldsmiths College, London, and it had been kidnapped by Nottingham students.

At the start of the Second World War the staff and students of Goldsmiths College were evacuated to Nottingham, and they shared the campus with the members of University College Nottingham. A good-natured rivalry sprang up between the two colleges, resulting in a number of pranks played by one on the other, of which this was one. It is described with relish in the student newspaper for 23rd February 1943.

The next issue of the student newspaper confirms that the £5 ‘ransom’ demanded from the college principal for the return of Mrs Criker was paid to the Ram Nahum fund. The fund was collecting in memory of Effraim ‘Ram’ Nahum, who was a Physics graduate student, and communist activist, at Pembroke College Cambridge. He was killed by a German bomb which fell on the city in 1942.

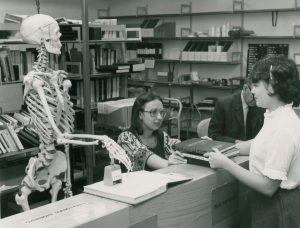

Interactions between students and skeletons have continued, as has the urge to use them for jokes; a series of photographs taken in the 1970s at the new Queens Medical Centre includes one where the Medical School’s model skeleton is helping in the Medical Library, about to stamp a book and loan it to a student!

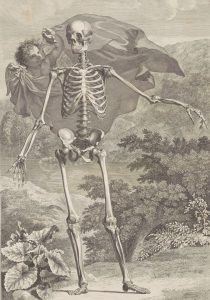

Of course the more valid reason for the contact between students and skeletons is in the name of education. The study of skeletons is a vital part of the training for medical students, archaeologists, and even artists. The books and documents held at the library of Manuscripts and Special Collections include many educational books and treatises examining the skeleton for the benefit of prospective doctors, such as this image from the 1749 anatomical atlas “Tables of the Skeleton and Muscles” by Bernhard Siegfried Albinus, who was Chair of Anatomy and Surgery at Leiden University in Holland.

From B.S. Albinus ‘Tables of the skeleton and muscles of the human body’ (1749). Ref: Med Chi Collection Over.XX WE17 ALB

Today most teaching skeletons are plastic models, like the one in the library photograph above, but before the invention of suitable plastics actual human skeletons were used. We don’t know for certain, but it is likely that Mrs Criker was a real skeleton.

The use of human remains for education has always been a controversial subject. Dissection of human bodies was prohibited in Britain well into the medieval period. Formal medical education, which began at Oxford and Cambridge universities in the 13th century, focused on learning from texts written by ancient authors. The primary authority was Galen, who lived in Greece in the 2nd century AD. For centuries Galen’s writings were accepted virtually without question. In the 16th century some continental physicians, such as Paracelsus in Switzerland, started to emphasise the value of observation as well as ancient wisdom, and in the middle of the century the Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius conducted dissections of human cadavers and began to publish his own empirical observations, which refuted some of Galen’s suggestions. The medical profession began to accept the value of dissection and study for learning.

In England, from the 16th century onwards, certain specific groups began to be granted the right to dissect the bodies of hanged criminals. These included the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, as well as the Royal College of Physicians and the Company of Barber-Surgeons. These dissections were infrequent, however, and by the mid-19th century the teaching of medicine had expanded so much that that the number of bodies available for study was insufficient. The Anatomy Act was passed in 1832, allowing the corpses of people who died in workhouses and charitable hospitals, and who were not claimed by relatives or friends, to be used for study. This was regardless of the will of the person in life! Since the late 20th century the bodies available for educational dissection in the UK have all been donated voluntarily before death.

As well as its use for practical education the skeleton has also been a motif for moral and religious education. A skeleton is an image which can be used to symbolise death. Medieval Christianity developed the notion of ‘memento mori’, or remembering that you are mortal and will die, as a focus for reflection on the afterlife and how earthly acts may affect the fate of the soul. This led to an artistic tradition of using images related to death to comment on vanity and morality. Memento mori are common additions to paintings, texts, and memorial architecture, such as this example from a monument in St Mary’s Chapel, Clifton, erected around 1620 by Sir Gervase Clifton in memory of this first three wives.

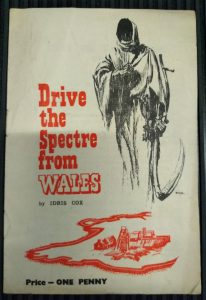

Artists and designers have also exploited this connection between the skeleton and the idea of death. It can be used as a powerful image to suggest a vital threat, such as a disease or war, and is therefore often seen in political and other propaganda. This leaflet was published in 1946 by the Welsh Committee of the Communist Party, and uses a looming skeletal figure to suggest that the spectre of unemployment is threatening the lives of the people of Wales. Scary indeed!

All these items and more can be seen in our Reading Room at King’s Meadow Campus. Find out more about our collections from our free newsletter Discover, or follow us @mssUniNott.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply