June 17, 2018, by Kathryn Steenson

Mum’s gone to Iceland

Famous for its harsh landscapes and heroic sagas, Iceland was a source of endless fascination for 19th century travellers.

Many were sent on geological, botanical or other scientific expeditions. Ida Pfeiffer was different. Born in Vienna in 1797, she was bitten by the travel bug aged 5 when she accompanied her parents to Palestine and Egypt. Her father gave her the same education as her brothers and allowed her to be a sports-loving tomboy, but after he died, Ida’s mother insisted on a much more conventional upbringing for her daughter. Ida married a much older widower in 1820, by whom she had two sons, and the combination of motherhood and a period of financial difficulty made her dreams of travel unobtainable until the 1840s.

By then, her husband had predeceased her and her sons were adults. It breached societal norms for women to travel unaccompanied, but she was a middle-aged, independently wealthy woman whose desire to see the world had not diminished over the decades she had spent living in respectable conformity.

Iceland was one of the places Ida had longed to visit since childhood, to find “Nature in a garb such as she wears nowhere else…I hoped to see things which should fill me with new and inexpressible astonishment”.

Ida journeyed to Scandinavia and Iceland in 1845. It was her second expedition (the first being to the Holy Land) and fortunately for us her astonishment proved eminently expressible, although this two-volume account was not published in English until 1852. She spent a large portion of the preface defending herself against accusations of eccentricity, attention-seeking and other misogynistic condemnation from people who rarely encountered a landscape wilder than an unkempt lawn.

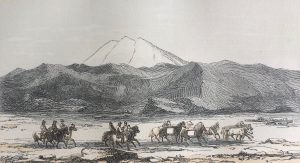

Ida could give as good as she got, and she was not immune from doling out her own sharp criticism. She loved Iceland but founds its people indolent drunkards. She travelled there between 15 May and 29 July, during which time there were only a couple of hours of darkness each night and the days reached unseasonably warm temperatures of 20C. Many Icelanders complained they were unable to work in such heat and waited until it became cooler in the late afternoon and evening, whereas Ida preferred to set off before 7am.

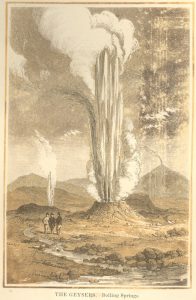

The highlight of her trip was seeing the Great Geyser erupt. She camped alone there for two nights, fearful of missing an eruption but not trusting an ‘Icelandic peasant’ to keep watch for her. Her patience was rewarded and she described the ‘magnificent and overpowering’ eruption in her diary, recording the sight, smell, and taste of the geyser pools.

“The water spouted upwards with indescribable force and bulk….how little [my tent] seemed as compared to the height of these pillars of water!…Without exaggeration, I think the largest spout rose above 100 feet high and was three to four feet in diameter”.

Ida herself proved something of an attraction. In Krisuvik the priest arranged for her to stay overnight in the 22ft chapel, and she recounts – with growing frustration – that the entire community packed into the building to watch her eat, write and boil coffee. Once she sent them away, she could not relax and spent a restless night that she attributed to sleeping alone in a church, in the middle of a graveyard, listening to a howling storm outside.

Ida Pfeiffer journeyed around the world twice and became a celebrated travel-writer, and the money from her books allowed her to travel further. She died in 1858 in Vienna from an illness that may have been exacerbated by the malaria she contracted the year before in Madagascar.

Iceland celebrates Lýðveldisdagurinn (National or Independence Day) on 17th June. In May 1944, 98% of Icelanders voted to abolish the Union with Denmark and adopted a new republican constitution to become an independent country. Ida’s book ‘Visit to Iceland and the Scandinavian North’ (Travel Collection DL312.P4 barcode 6001982150) and our other Iceland travel accounts are available to view in the Reading Room. We have both the original and published versions of the journal of Alice Selby, lecturer in English at The University of Nottingham, kept during her tour of Iceland in the 1930s. We also have the volumes produced by Ólafsson and Pálsson (Travels in Iceland, 1805), Sir George Steuart Mackenzie (Travels in the Island of Iceland, 1812), and Sabine Baring-Gould (Iceland: its scenes and sagas, 1863), all of which contain beautiful plates and images of Iceland’s landscapes, towns and people.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply