September 26, 2016, by Kathryn Steenson

It’s All Fun and Games

Did you play Snakes and Ladders, hopscotch and draughts as a child? The chances are you did, as did your grandparents, and possibly generations beyond that. These games are simple and fun, and for those reasons have become classic childhood staples. Many more games which have not survived the passage of time, for equally valid reasons.

Nineteenth-century children’s board games were opportunities for education and moral instruction as well as amusement. They were marketed at middle or upper class households, and were often designed for playing quietly with a tutor, governess or parent.

A common format was a board made of thick paper backed onto linen, which was both durable and could be folded away neatly into a card case. The counters and teetotum were not usually included and the assumption that every home would already have them shows how popular this style of game was. A teetotum was a spinning top with numbers on it, used instead of dice, which were associated with gambling and therefore unsuitable for children’s games.

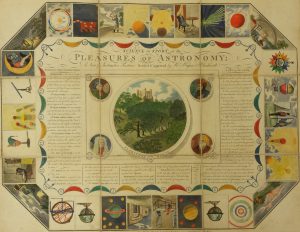

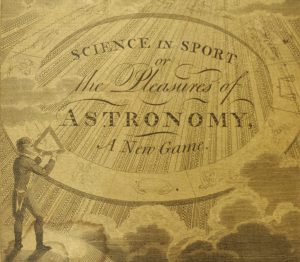

The rules of this game from 1804, ‘‘Science in Sport, or The Pleasures of Astronomy’ (Ref: Briggs Collection Game X-28) are quite simple and typical of the format. Each square featured a different image and as players moved round the board, they were required to read a related fact aloud (statistics related to the planet depicted in the image, for instance), or correctly answer a question (e.g. explain how a telescope is used) on penalty of missing a turn. The winner was the first to get all their counters to the Royal Observatory at Flamstead House and became ‘Astronomer Royal’.

One notable point is that this game was considered suitable for both boys and girls, despite being a scientific subject. It was endorsed by ‘Mrs Bryan’, about whom almost nothing is known except her name, Margaret Bryan, and that she was a schoolmistress in Blackheath who authored several scientific textbooks. One of them (Compendious System of Astronomy) depicted her and her two daughters in the frontispiece. Her name attached to the game was meant to reassure parents of its accuracy and educational merit as well as its suitability for young ladies. What is lacking is any claim that the game is fun, or that children would enjoy playing it.

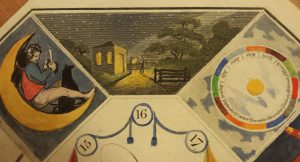

Beautiful illustrations depicting the Man in the Moon (a penalty square), conducting astronomical observations at night (a rest square), and the Sun surrounded by the calendar (a question square) (Briggs Games X 28

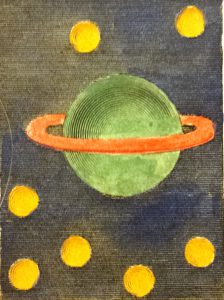

Illustration of Uranus, with a red ring and 7 moons. The existence of rings was suggested in 1789 but not confirmed until 1977 (Briggs Games X 28)

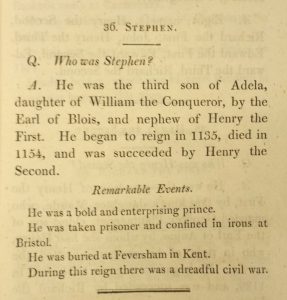

Fun is also conspicuously absent from ‘An historical game of the Kings of England: including the memorable events of their reigns, adapted to the juvenile capacity’, again from 1804 (Ref: Briggs Collection Game x-17), which would have done little to dent the tedium of a wet afternoon indoors.

The game takes the form of a family tree with each monarch – despite the title, it does include the Queens and Commonwealth – named in numbered pink or yellow circles from the Britons to George III (1738-1820). Those circles before William I (the Conqueror) are pink and those after are yellow.

Unusually, our copy contains 51 of the original 73 numbered counters, suggesting the game wasn’t played too often. The counters were put into a bag and each player would draw one out, matching the number to a corresponding monarch. The children would recite a series of facts about that monarch, his or her reign, or the era generally, and were rewarded with tokens for correct answers. The accompanying rule book states that:

“[the pupil] who has received most is entitled to some little gift, which it is requisite parents and tutors should hold out to awaken emulation in the breast of the youthful pupil.”

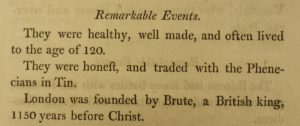

The game perfectly encapsulates the outdated style of rote learning that could result in pupils knowing lots but understanding little. Below is the whole entry for Stephen I, which shows it was not, according to the rules of the game, necessary for players to understand what caused the 20 years of civil unrest that was the defining characteristic of his reign, or to even know of Empress Matilda.

Monarchs are frequently described as ‘virtuous’, ‘wise’ or ‘weak’, but rarely are examples of such behaviour are presented. Some facts were downright dubious, such as claiming that Britons ‘often lived to the age of 120’.

The probably-mythical King Brute (or Brutus) and his equally-unlikely 120 year old subjects (Briggs Game X 17)

These popular and mass-produced games were adapted to cover subjects as diverse as geography, manufacturing, natural history and religion. We hold many more games as part of the Briggs Collection of children’s educational literature, ranging from fairy stories for infants to textbooks for older children.

They are among the collections held at Manuscripts & Special Collections at King’s Meadow Campus. To make an appointment to view the archives and rare books, please contact us. More information about our collections is on our website. For general information, read our newsletter Discover, or follow us @mssUniNott. If you’re looking for slightly more modern ways to combine education and entertainment, why not come along to the Family Fun Day on Saturday 1 October at Lakeside Arts, University Park Campus?

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply