July 25, 2016, by Kathryn Steenson

Dead Man Found in Coffin

What are Horseshoehead, Purples, Tissick, and Rising of the Lights? If you guessed along the lines of an equestrian accident, a colour, a small village in the Home Counties, and perhaps an indie band on the verge of greatness, then you’d be very wrong. These are just a few of the bizarre-sounding medical conditions that were killing people in the summer of 1716.

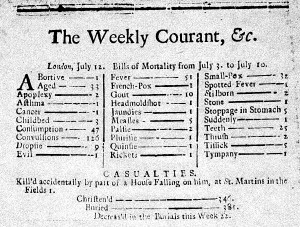

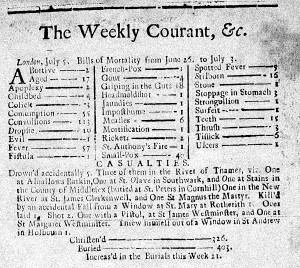

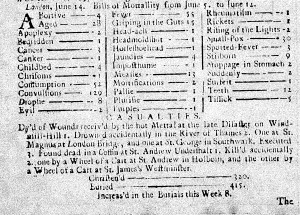

These entries are taken from the Bills of Mortality, which were regularly published in newspapers across the country despite the data being from London. Listed amongst the deaths from fevers, childbirth, smallpox and measles, are a range of ailments completely unfamiliar to the modern reader. They were originally recorded in the 16th century as a means of keeping track of plague burials in the City of London. Gradually, as London expanded, so did their geographical coverage, and it became routine to collect the statistics weekly even between plague outbreaks. They’re by no means accurate as they record only Church of England burials. Extra-parochial churches or burial grounds for different faiths were excluded, so it’s estimated that about a third of deaths were missed off the Bills.

Here’s a list of what Londoners were dying from in summer 1716:

| Abortive | 7 | Imposthume (cyst) | 2 |

| Aged | 78 | Measles | 24 |

| Apoplexy (stroke) | 6 | Mortification (gangrene) | 3 |

| Asthma | 1 | Palsy (loss of function, possibly caused by a stroke) | 3 |

| Bedridden | 1 | Pleurisy | 2 |

| Cancer | 4 | Purples | 1 |

| Canker | 1 | Quinsy (swelling in the throat) | 1 |

| Childbed | 11 | Rheumatism | 1 |

| Chrisoms (infants) | 1 | Rickets | 4 |

| Colic | 3 | Rising of the Lights (croup) | 2 |

| Consumption | 154 | St Anthony’s Fire (fever with red inflammation) | 1 |

| Convulsions | 368 | Smallpox | 101 |

| Dropsy (Oedema) | 27 | Spotted Fever (typhus) | 9 |

| Evil (King’s Evil i.e. scrofula, or glandular TB) | 4 | Stillborn | 27 |

| Stone (gall stones) | 2 | ||

| Fever | 113 | Stoppage in the Stomach | 10 |

| Fistula | 1 | Strongullion (possibly bladder disease) | 1 |

| French Pox (venereal disease) | 2 | Suddenly | 3 |

| Gout | 14 | Surfeit (overeating) | 2 |

| Griping in the Guts (diarrhoea) | 33 | Teeth (infants deaths attributed to teething) | 52 |

| Headache | 1 | Thrush | 3 |

| Headmoldshot (skull deformities caused by difficult childbirth) | 3 | Tissick (Consumption i.e. tuberculosis) | 16 |

| Horseshoehead (inflammation of the brain in infants) | 1 | Tympany (abdominal obstruction causing swelling) | 1 |

| Jaundice | 3 | Ulcers | 1 |

All of these have to be taken with a pinch of salt, as many diseases with similar symptoms were grouped together, like the mysterious ‘purples’ that killed one poor Londoner. It was named after the marks under the skin caused by small bleeds, which could have been caused by anything from scurvy to fevers.

Casualties included fairly routine misadventures and accidents, such as drowning in the River Thames (it was a very hot, dry summer), being run over by a cart in the street, and falling (deliberately and accidentally) from windows. Any interesting back-stories behind the execution, the man who was killed when part of a house fell on him, and the titular man found dead in a coffin in St Andrews, are, unfortunately for the idly curious, are omitted from the Bills. The only one where further explanation is possible is the man who ‘dyed of wounds received by hot metal at the late Disaster on Windmill Hill’.

The disaster was the explosion in the Royal Brass Foundry that cast brass cannon. The molten metal being poured into moulds came into contact with moisture. Seventeen people died from the resulting steam explosion, either immediately from the force of the explosion that completely destroyed the building, or, as in this case, shortly after of burns caused by the molten metal. It must have been an excruciating few days.

It’s incredibly interesting to look back and see what people were dying of in the drought-ridden summer 300 years ago. This morbid curiosity, plus a desire for content, were the primary reasons why Bills of Mortality were included by the fledgling newspaper industry, as unfortunately there were no local equivalents. These images are from what was likely Nottingham’s first newspaper, The Weekly Courant, published by William Ayscough in August 1712. It was followed by The Nottingham Post in 1716, which Ayscough took over in 1723 before launching another newspaper The Nottingham Weekly Courant. Nottingham had gone from having no regular newspapers to three in little more than a decade.

If you’d like to see more, we have a selection of local newspapers on microfilm available in the Reading Room. If mention of archaic disease has caught your attention, then please have a look at our Health Resources subject guide, which gives details about our medical collections like the Medical Rare Books collection and Med Chi Society records.

To book an appointment, please email us. You can also follow us on Twitter @mssUniNott.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply