March 17, 2016, by Kathryn Steenson

The Advantage of Fairy Tales

This is a guest post from Samina Rickards, a second year Classical Civilisation student.

These past weeks I have been conducting a placement at Manuscripts and Special Collections, as part of the Nottingham Advantage Award’s ‘Experience Heritage’ module.

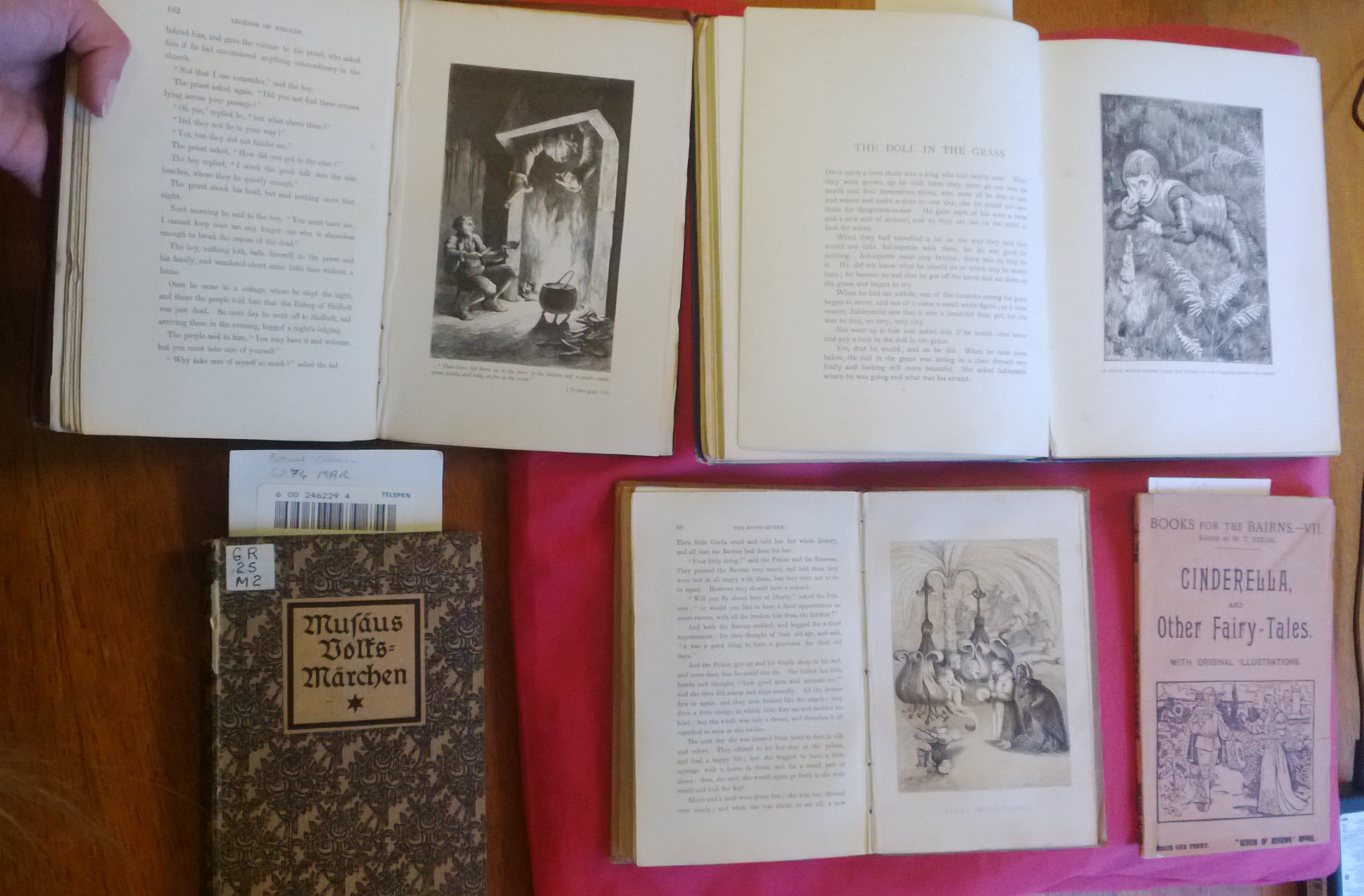

In writing a blog post on my time here I wanted to highlight something I’d found interesting, and desired the chance to explore in more detail. One of my tasks was to develop a small display for the Reading Room, selecting the material and writing accompanying captions. I used this opportunity to explore one of my own interests, and searched the catalogue for material on fairytales and folklore. I want to convey the fascination this held for me through one item in which I encountered a surprising wealth of history, something touching and, perhaps, something a little disconcerting.

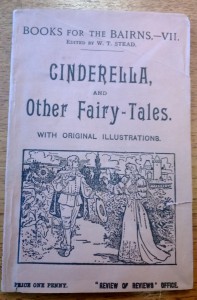

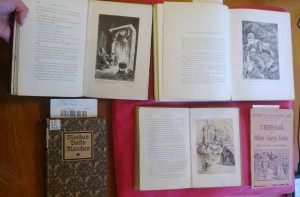

I had to select possible material for my display prior to seeing it, and order it from storage. Choosing books listed as illustrated, which would be engaging for display, and representing fairy tales in a wide range of cultures, a battered pamphlet listed under the title ‘Favourite Fairy Tales’ initially seemed one of the less interesting articles. It contained primarily stories well known in the English language (Cinderella, Beauty and the Beast, etc) and compared to many of the other books, beautifully bound books with elaborate illustrations, was not visually striking.

However, seeking information for the caption, I researched the pamphlet’s creator, one William Thomas Stead, and was shocked to discover his truly extraordinary history, rather at odds with the obscurity of his name. A radical liberal journalist of the Victorian era, Stead had been a vocal feminist- advocating universal suffrage for both sexes and better education for women- an opponent of the Poor Law and committed to the improvement of child welfare. Horrified to discover a circle of child prostitution among the upper classes, which many establishment figures had turned a blind eye to, his outraged response became instrumental in having the age of consent raised from 13 to 16. Yet, somewhat absurdly, Stead became the first victim of the change he’d worked for, having staged the ‘purchase’ of a 13 year old girl in a bid to prove the injustice of the law. Either the justice system so hinged on technicalities as to ignore the reality of the situation, or perhaps his persecution was meant to mollify his critics. In any case he was imprisoned and after his release he kept, and with eccentric defiance continued to wear, his convict’s uniform; presumably as a statement of pride in what he’d done.

However, seeking information for the caption, I researched the pamphlet’s creator, one William Thomas Stead, and was shocked to discover his truly extraordinary history, rather at odds with the obscurity of his name. A radical liberal journalist of the Victorian era, Stead had been a vocal feminist- advocating universal suffrage for both sexes and better education for women- an opponent of the Poor Law and committed to the improvement of child welfare. Horrified to discover a circle of child prostitution among the upper classes, which many establishment figures had turned a blind eye to, his outraged response became instrumental in having the age of consent raised from 13 to 16. Yet, somewhat absurdly, Stead became the first victim of the change he’d worked for, having staged the ‘purchase’ of a 13 year old girl in a bid to prove the injustice of the law. Either the justice system so hinged on technicalities as to ignore the reality of the situation, or perhaps his persecution was meant to mollify his critics. In any case he was imprisoned and after his release he kept, and with eccentric defiance continued to wear, his convict’s uniform; presumably as a statement of pride in what he’d done.

A superstitious man, he’d gone on ghost hunts with Sherlock Holmes’ author Arthur Conan Doyle (though this rather bizarre behaviour sadly undermined his public image and the credibility of his journalism in his later years). He published a number of children’s book in cheap pamphlet form, affordable for poor families, of which ‘Favourite Fairy Tales’ (or ‘Cinderella and other Fairy-Tales’) was one. Stead’s ending was suitably dramatic, the more so for his having purportedly predicted it beforehand: he drowned in the sinking of the Titanic, apparently spending his last moments helping other passengers onto lifeboats.

Stead’s concern for improved education and welfare is apparent in his preface to ‘Favourite Fairy Tales’: he expresses concern that children raised without could suffer ‘spiritual destitution’, and his hope to make these classics stories the ‘privilege of the poor’ as well as the rich. Yet Stead was apparently an advocate of fairy tales considered as classics, and the right of every child equally, without necessarily considering their specific implications. One story he includes entitled One-Eye, Two-Eyes and Three-Eyes has some uncomfortable undertones: a woman has three daughters, one with one eye, one with two and one with three. Naturally the ‘normal’ Two-Eyes (in literal fairy tale fashion, the three daughters appear to be named after the number of eyes she has) is the heroine, and the victim of her monstrous family’s abuse. This masterful, yet not pleasant, stroke at once allows us to pity the abused outsider, while maintaining a clear status quo which discourages sympathy for the ‘other’ as monstrous. Simple child’s story as it is, one would still think this might have struck the ultra-liberal Stead as unpleasant. Perhaps he simply accepted the story’s allegory more loosely than I read it – after all, in Two-Eye’s inevitable rescue and noble marriage, the oppressed triumphs over the oppressor, and it was this conflict which dominated Stead’s extraordinary life.

These books, and many more relating to children’s literature and fairy tales, are available in the Reading Room on King’s Meadow Campus. If you would like to view them, or any of our holdings, please contact us. For more information, see our website, follow us @mssUniNott, or read our newsletter Discover. Samina’s display will be in the Reading Room later this summer.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply