February 26, 2016, by Kathryn Steenson

Dark, Satanic Mills

In late January and throughout February 1828, readers of the radical newspaper The Lion were amongst the first to read excerpts from an astonishing memoir that would help change Victorian Britain’s textile industry, and possibly inspire one of the great works of English literature.

A Memoir of Robert Blincoe was published in its entirety four years after its serialisation. It was hugely successful and probably come to the attention of Charles Dickens (born 204 years ago this month) during the period he wrote Oliver Twist, published 1837. In his book, Dickens was criticizing the Poor Law; Blincoe the system of indentured apprenticeships, but both were concerned about exposing the exploitation of orphans and child labourers.

Robert Blincoe (d.1860) was born in London c.1792. By 1796 he was an orphan in St Pancras workhouse, where his nickname was ‘Parson’ after rumours that he was the illegitimate son of a priest. He never discovered his parentage and it’s unlikely any information can be found, as his surname may have been bestowed on him by the workhouse.

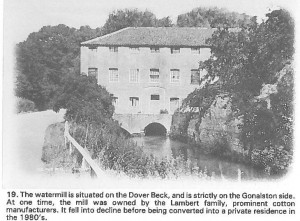

Conditions were hard, but he was clean, properly clothed, and the food was adequate, if uninspiring. Much like Oliver Twist, he narrowly avoided being apprenticed to local chimney sweep, before he was among eighty children sent from the workhouse as textile apprentices, first to Lambert’s mill in Lowdham, Nottinghamshire, then after it closed in 1802, to Litton Mill, Derbyshire.

Promised schooling and a better life outside London– falsely, as an illiterate Blincoe had to dictate his memoir to journalist and factory reform campaigner John Brown – he was instead put to work making stockings and lace for 14 hours a day. Blincoe describes his horror at the noise of the machinery and the stench of grease and oil, both on the equipment and on the clothes and bodies of the apprentices.

Starved, beaten and exhausted, the seven-year-old Blincoe attempted to run away, but was caught on the road between Lowdham and Nottingham and returned to the mill. He remained working in the mills until his apprenticeship finished in 1813. His loss of a finger in the spinning frame pales in comparison to his account of a girl having every limb crushed after she was dragged into the machinery at Lowdham Mill by her apron. Many more of the overworked and underfed apprentices at Litton Mill died in epidemics that swept through the crowded dormitories.

Blincoe acknowledges that these conditions were the extreme. Urban mills were more easily monitored by the authorities. The mills where he worked were in remote, sparsely-populated regions with little oversight of the youngsters sent to work in them. Parish Councils had always attempted to find apprenticeships for pauper children, to prevent them being a burden on the parish and to equip them with a trade that would support them in adulthood. As both the population and industrialisation increased, children were not always apprenticed to skilled craftsmen, but sent en masse to little more than industrialised slavery.

Image of C W and F Lambert’s mill from ‘Lowdham, Lambley and Gonalston on old picture postcards’ (Ref: EMC Pamphlet Not 268.D34 OTT)

John Doherty, a key figurehead in the Ten Hours Movement to limit the national working week, published Blincoe’s Memoir in 1832. As a result, Blincoe was invited to speak before the Employment of Children in Manufactories Committee as part of the government investigation into working conditions.

The connection between Twist and Blincoe is the subject of John Waller’s book The Real Oliver Twist (DLRC, Jubilee Campus HD6250.G7.W2). As well as some similarities between their stories, including the hint of a higher birth, it is unlikely Dickens would have been unaware of Blincoe. However, the connection is contentious, as Dickens never mentioned Blincoe, and his experiences working in a factory after his father’s bankruptcy would have provided more than enough fuel for his imagination.

Perhaps the biggest difference between the two is their personalities. Oliver Twist is insipid saintliness personified, whereas Blincoe was resourceful and had the strength of character to campaign against a system that broke the spirits and bodies of so many of his contemporaries. Despite a period of bankruptcy following a devastating fire that destroyed the first business he set up, he became a successful businessman who encouraged his children’s education and kept them out of the mills.

Litton Mill, now luxury apartments and holiday accommodation, pictured in 1988. From ‘Not ours, but ours to look after’ (Ref: EMC. os.Pamph Der 695.G12 LIT)

These books and many others can be viewed in the Manuscripts & Special Collections Reading Room. For more information about child labour, please see our online display.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply