November 20, 2015, by Nicholas Blake

The Unloved Chimney

In the Feb 1st 1968 issue of University of Nottingham student newspaper Gongster there appeared a riddle. “What am I?” it teased. Even more excitingly, it suggested that if you were to aid this forgetful soul in establishing its identity then “a reward may well be given”.

The riddles’ clues were, for the most part, fairly matter of fact. For example, “I am triangular,” it said. “I prevent blue haze”. Then it described its diet of gravel, sand, cement and porcelain bricks. While this may sound unappealing, it certainly hadn’t stunted its growth, as revealed when it coquettishly declared its measurements: a floor span of 12 feet, and 43 ½ yards tall (“and still growing fast”). If those clues weren’t enough, it divulges some more. “Mr Swanson looks after me,” it says. Sadly, though, even Mr Swanson couldn’t stop the bullying: “I am told that I am hideous”.

What tragic being could this be referring to? What poor unfortunate was being attacked for its looks? And just what is “Blue Haze”? (Google helpfully informs me that it is either a type of marijuana or a Miles Davis album. Thanks, Google.) Although it was forty seven years too late to claim a prize from the student newspaper, my curiosity had been piqued.

Thankfully my burning quest for truth was satiated in the next issue of Gongster, where Mr J.R. Prince was revealed to have the winning answer. “Dear Sir,” he wrote, “You are a bloody great hump of chimney sticking out of the central heating station.” If that wasn’t rude enough, he then went on to slag off its blue haze prevention abilities. (Apparently recreational drugs and hard bop jazz aren’t for everyone.)

At first I couldn’t think I’d ever been anywhere near this chimney. Then, seeing a photograph of it, towering over the science buildings on University Park, I realised how often I’d noticed it and then instantly forgotten it. Is it really true that nobody has any love for it? Time to investigate.

I started with going through our own material here at Manuscripts and Special Collections. The University’s annual report for 1966-67 (UoNC Periodicals Not U) makes reference to the boiler house being adapted for the installation of a fourth boiler, with the inclusion of a new chimney. Due to be completed by March 1968, the report boasts the structure will “rival the Architecture building and the Trent Building tower in height” (p.15). There would be no hiding for this chimney.

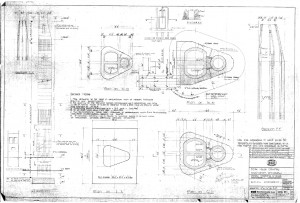

Our holdings of the University’s Council and Senate minutes proved disappointing, with only a very brief mention to the building works, but the current University Estates team were much more helpful. They were able to tell me that although the chimney was originally built for coal fired plant, for as long as anyone can remember the boiler house has used gas fired heating plant. They also very kindly let me see some of the original plans of the chimney which prove to be resplendent technical drawings, dynamic and intricate, ignorant of the bullying the chimney would receive once built.

Meanwhile, a plea for anecdotal evidence turned up a glutton of rumours from my fellow staff members: “They built it facing the wrong way which is why it never worked properly”; “a maintenance worker once got into difficulty when a gust of wind caused his ropes to tangle and he had to be rescued”; “the black smoke is caused by burning students who wouldn’t pay their library fines.” Citations needed all round.

Unfortunately, tracking down any more concrete information on the chimney seems next to impossible. Facts elude me, disappearing from view in the murky (blue) haze of hearsay. We may never know who Mr Swanson was, for example. Or why everyone seemed to take against the chimney’s existence quite so vehemently. All we know is that this is a chimney unloved by all.

Except, wait… That’s not quite true.

For BBC Radio Nottingham’s John Holmes, a Mining Engineering student at the University in 1968, the chimney’s construction is a source of happy memories. “We used to leave the Buttery [student bar] at closing time,” he says, “and after saying goodbye to girls would meet at the top at midnight.”

By climbing up the scaffolding John was able to take these photographs from the chimney’s impressive height. “I still smile when I see it,” he says.

Turns out there is some love for an ugly chimney with an identity crisis after all.

Chimney covered in scaffolding during construction, June 1968. (ACC 2170/5) Photograph by John Holmes.

Addendum – September 2017

Since the original blog post above was published some additional information about the chimney has come to light.

We were contacted by the family of Denis Jones, supervisor of the original construction of the University’s boiler house chimney. Mr Jones, now in his late eighties, agreed to write a short piece about his memories of the construction. His account is now part of our archive collection about the University (ACC2863) and is reproduced below with his permission:

“In the mid 1960’s when I was Clerk of Works at the University of Nottingham the job came up of building a tall chimney for the new central boilerhouse. It was to be 200 feet high, constructed in concrete.

The Clerk of Works’ job is to ensure on behalf of the client that any construction is in full accordance with the architect’s or engineer’s plans and specifications, and ensure that contractors do not take any money-saving or quality short cuts of any kind. He is quite a powerful person on a building site.

My boss, the senior C.o.W. (there were three of us) took one look at the plans for the chimney and said, “Denis, you’re the rock climber, this one’s yours”.

The early stages of construction were alright, being mainly foundation works at ground level. But then it started to grow at the rate of four feet every three or four days. The chimney was triangular on plan with rounded corners, the shape being formed with plywood shuttering bolted in position. I had to check every day that all was in order with the steel reinforcement before allowing any concrete to be poured. The construction team comprised scaffolders who surrounded the chimney with scaffolding as the job progressed, and the chimney specialists who fixed the shuttering and steel bars ready for concrete. Four feet per stage.

All was well for the first fifty feet or so as access was by ordinary ladders angled inside the scaffolding, but after that the ascent was continued by means of vertical steeplejack ladders up the outside of the scaffolding.

Many experienced and famous mountaineers and climbers have admitted that, without understanding why, and for no obvious reason, they are most uneasy and unhappy when in an exposed position on man-made constructions like rooftops or parapet edges. Logically it is more dangerous on a vertical rock face with vestigial holds, relying on faith and friction, and yet there is not the same sense of insecurity as that experienced on high ladders.

As I got higher in my daily climb I would stop half way up, entwine myself in the ladder and pretend to be having a rest, whilst actually screwing up courage to continue. The important thing is to keep three points of contact at all times – only one hand or one foot should be detached and moving to the next grip, but keeping it smooth and rhythmic so it is not obvious to spectators that you are clinging on for dear life. At the back of one’s mind is the knowledge that the acceleration due to gravity is thirty-two feet per second per second, and the climber’s adage that it’s not the distance you fall that does the damage, it’s the sudden stop.

So every morning I had to steel my resolve and climb up that vertical outside ladder, higher by the week, with a completely false air of nonchalance. Once at the top there was no problem, height in itself was no worry and the views over Nottingham and the Trent valley were panoramic. But when I had agreed that all was in order I had to face the worst moment of the day – climbing out over the top handrail of the scaffolding and out onto that vertical outside ladder. Going down was no less nerve-racking than going up, but even bad things come to an end and construction was eventually completed.”

As it turns out, Denis Jones wasn’t the last rock climber to ascend the chimney. I recently discovered this article, once again from the student newspaper Gongster, about an expedition up the chimney undertaken by two members of the University’s Mountaineering Society in early 1970.

The students began their climb at 7am using the scaffolding bolts left behind by construction to affix their equipment. This was a slow and laborious process and it ended up taking them eight hours to reach the tip of the chimney, twice as long as they estimated. Thankfully it only took them half an hour to get safely back down again.

The expedition was unauthorised, and to avoid the wrath of the boilerhouse caretaker who was alerted to what was going on during the climb, the students claimed they were doing maintenance work. In the article, Gongster congratulates them for their “successful double feat of mountaineering and deception”.

If anyone has any more information or reminiscences about the chimney, do share your thoughts in the comments below!

With thanks to Mark Bonsall, John Holmes, Denis Jones and Susan Jones.

So if it was built for coal but the plant uses gas, what does the chimney do now? Is it still a functioning part of the boiler, or just a relic?

My office sits nicely under this along with the rest of the Estates office. There are gas boilers which do require a flue/ chimney but nothing like the height of this. We’re developing plans to install a combined heat and power plant to generate both electricity and heat (connected to the district heating network) at present. We’re also reviewing options for the chimney …

interesting article…my father-in -law Denis Jones designed this chimney when he was chief draughtsman at Nottingham University back in the ’70’s. As clerk of works he also had oversight of it being built. He is now in his late 80’s but very fit and healthy and would easily write an article or answer any questions regarding it.

Thank you for the offer – someone will contact you shortly about this.