November 3, 2015, by Kathryn Steenson

Expressing the Unspeakable

A version of this post appeared on the University’s LGBT History blog earlier this year.

It’s often overlooked compared to Lady Chatterley’s Lover or its sequel Women in Love, but a century ago this month, D H Lawrence’s The Rainbow was the subject of a court case about sex, literature, and censorship.

The set-up is typical for a Lawrence novel: a working-class family, the Brangwens, live in the countryside at the Nottinghamshire/Derbyshire boundary. The plot follows their lives and often-difficult relationships down three generations, from rural farmer Tom and his Polish-born wife, to his educated and urban-dwelling granddaughter Ursula.

Lawrence wrote the book between 1913 and 1915. The novel ends in the opening years of the twentieth century, around the time when Lawrence, like his character Ursula, was finishing his studies and starting a career teaching in Nottinghamshire schools.

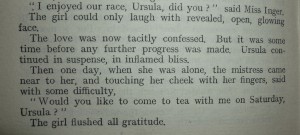

Whilst at University, Ursula has a brief relationship with her tutor, Miss Winifred Inger, “a rather beautiful woman of twenty-eight”. Ursula longs to know whether her love (or perhaps more accurately, her crush) is reciprocated, and has her question answered on a stiflingly hot summer’s evening when the two women go bathing. They soon become inseparable and initially Ursula’s affection for Winifred is ‘burning’ and ‘passionate’. The relationship fizzles out after a few months – Ursula’s affections waning more quickly than Miss Inger’s – and by the end of the chapter the latter marries Ursula’s uncle.

Unlike the film version directed by Ken Russell, the scenes in the book are all very tame and discreet, and far less explicit than some of the other intimate encounters in Lawrence’s works. This didn’t stop the moral outrage: the book was published in September 1915; the first condemnation by critics was published in October; and the publishers Methuen were prosecuted for obscenity in November.

The lesbian relationship was not the sole cause of the outrage but it was certainly a major factor. Critic James Douglas wrote that “the subtlety of phrase is enormous, but it is used to express the unspeakable and to hint at the unutterable”, which was itself rather euphemistic. He was more direct in his condemnation that The Rainbow‘s existence was disrespectful to the soldiers dying in France. Lawrence’s outspoken anti-militarism and German wife did not endear him to a society that had been engaged in a bloody war for a year. Clement Shorter’s review in The Sphere magazine was far more direct: “Let them [the publishers] turn to the chapter entitled ‘Shame’, and unless they hold the view that Lesbianism is a fit subject for family fiction I imagine they will regret this venture. The whole book is an orgie of sexiness”.

Douglas and Shorter’s criticism were presented as evidence for the prosecution. Methuen offered no defence at the trial, instead apologising for publishing the book, which was described by the court as “a mass of obscenity of thought, idea, and action throughout, wrapped up in a language which…would be regarded in some quarters as an artistic and intellectual effort”. (‘The Rainbow’, The Times, 15 Nov. 1915).

All the unsold copies of The Rainbow were seized and the book was banned in Britain for a further 11 years. Unlike the obscenity trial for Lady Chatterley’s Lover, there was little fanfare and little controversy. It continued to be available in America, which is where the sequel was first published, as British publishers were understandably cautious. Lawrence had originally intended The Rainbow and Women in Love to be one book continuing the story of Ursula and her sister Gudrun’s lives. Despite some controversy over the subject matter, Women in Love faced no legal action, and was published in Britain in 1921. This meant that the British public could purchase a copy of Women in Love some five years before they could read the prequel.

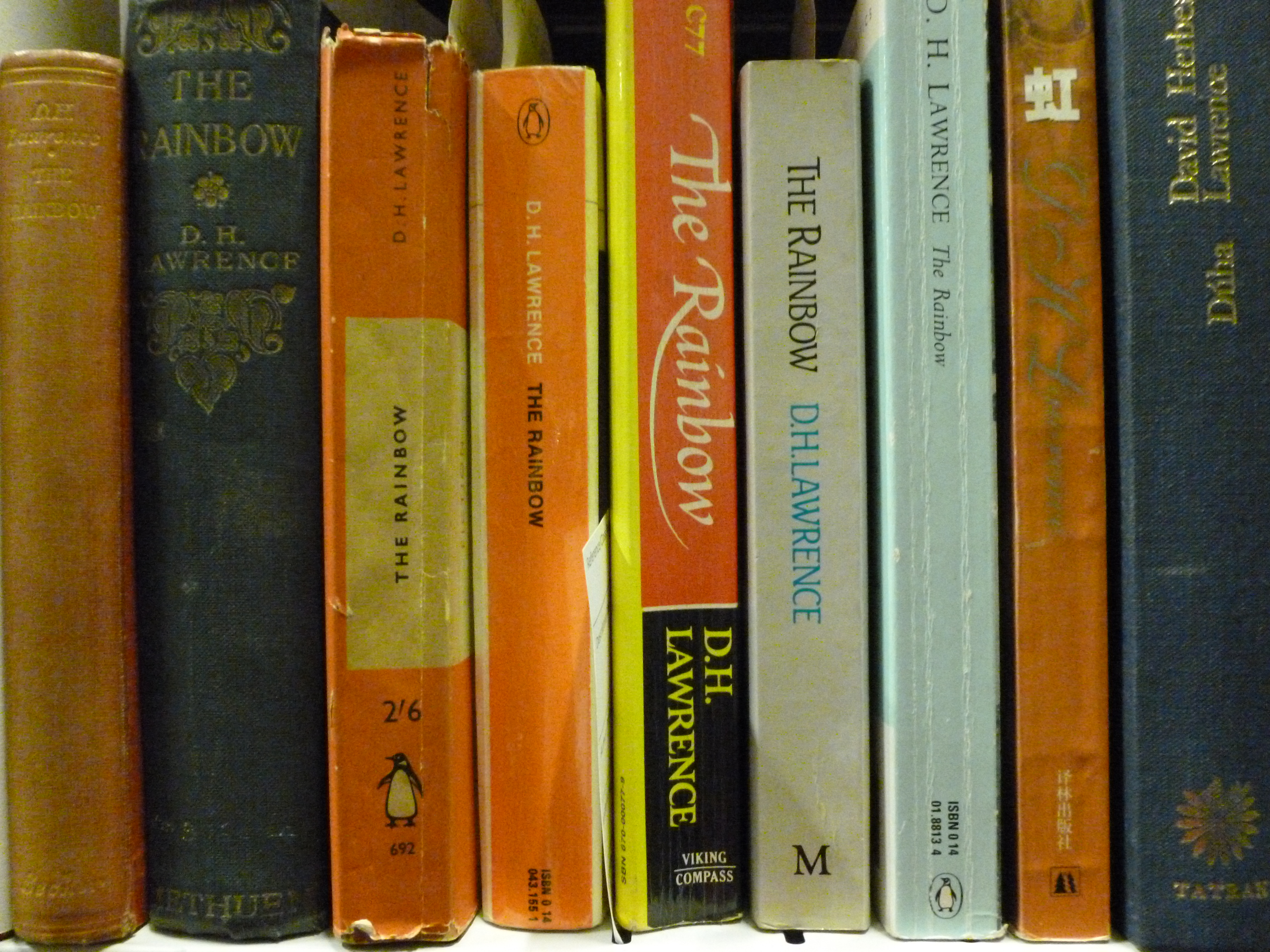

Manuscripts and Special Collections hold several versions of The Rainbow, including the 1915 version published by Methuen, and several later edited versions, which can be searched on the library’s online catalogue. More information about the trial, including copies of the two reviews quoted here, can be found by searching our manuscripts’ online catalogue.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply