August 13, 2014, by Kathryn Steenson

All Orders Promptly Executed

Fifty years ago today, 13 August 1964, the last two people to be executed in the United Kingdom were hanged. The victim was a 53 year old van driver named John West, who was killed during a robbery in his home that went wrong four months earlier. A neighbour had been awoken in the middle of night by loud noises and called the police, who found West with head injuries and a stab wound. Within days Gwynne Evans (aged 24) and Peter Allen (21), both of whom had numerous convictions for theft and burglary, were arrested and charged with murder.

Hangings were becoming increasingly rare by the 1960s, although the significance of Evans’ and Allen’s executions would not be known until capital punishment was officially abolished for murder. The last hanging in Nottinghamshire took place in 1928, with the last public hanging in 1861.

Then, as now, there was a section of the population fascinated by the details of gruesome or infamous crimes, and as always there were entrepreneurial souls willing to provide them. Cheap paper chapbooks were printed relating to notorious cases, their popularity peaking in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Many of these chapbooks were sold at fairs or at public executions, and incredibly were considered suitable reading for children, as a way to scare them into behaving.

They were as heavy-handed in their moralising as they were graphic in their content. Ostensibly intended to warn the public of the perils of drinking, gambling, failing to observe the Sabbath, and generally living a life of pleasure and excess, they also praised British values, the monarchy, and harsh punishments swiftly dealt. Much like today’s newspapers, where outrage over a scantily-clad singer or actress is invariably accompanied by large photographs, these pamphlets condensed as many sensationalist details (not all of them necessarily true) as they could into a dozen or so pages for the purpose of shocking their audience.

Inclusion of trial reports was common, as were biographical details of the people involved; a detailed account of the crime; the behaviour and last words of the accused at his or her execution; and, of course, illustrations. One, of the trial of Thomas Greensmith, who strangled his four children, even contains correspondence between Dr Blakes of the Nottingham Lunatic Asylum and the Home Secretary about whether or not Greensmith was insane and should be committed to the asylum rather than hanged. The pamphlet recounts the proceedings of the trial verbatim in parts, and although interesting, is a little too graphic to be quoted here. Those of you wishing to read it are welcome to view the “Report of the trial of Thos. Greensmith, before Sir James Allan Park, in the County Hall, Nottingham, Saturday, July 22, 1837 (Ref: EMSC Pamphlet Not 3.H64 GRE) at the King’s Meadow Campus.

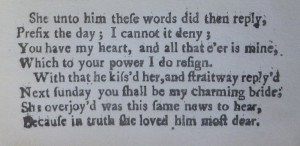

Despite being cheaply made and mass produced, we have several examples here, although some of them have definitely not aged well. A reprint of “The Nottingham Tragedy” (Ref: EMSC Pamphlet Not 3.H64 NOT), tells the story of farmer’s son John Painter, who murdered and mutilated his pregnant girlfriend Ann Chiswick after luring her to Sherwood Forest. The entire pamphlet is written in rhyming couplets – it’s a struggle to accuse it of being ‘poetry’ – and is accompanied by several crude and hastily-done woodcuts. It includes the text of a sermon preached on the occasion of the execution, under the pretext of being a respectable publication. The crime took place in about 1700, although Painter’s name is absent from “Wilson’s Gallows Hill Remembrancer: being a correct list of executions in Nottingham from 1201 to the present time” (Ref: Not 3.H64 WIL). This macabre publication was in its 8th edition by 1932.

The popularity of the chapbooks declined in part as executions moved inside prison walls from 1868, and sellers no longer had several hundred (or even thousand) potential buyers crowded at one place. They were beginning to be replaced in the early nineteenth century by the penny dreadful; cheap, serialised melodramatic tales of crimes and adventures that satisfied the target audiences’ need for escapism without the need for a terrible crime to be committed.

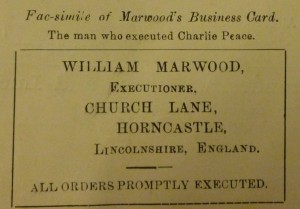

The final page of the “Gallow’s Hill Remembrancer” contained something that initially surprised me: this copy of a business card for William Marwood, Executioner.

A former cobbler in Horncastle before taking up executing people at the age of 54, Marwood developed the ‘long drop’ method of hanging, which instantly broke the prisoner’s neck and was thus a quicker and more humane method than slow asphyxiation. There is nothing else remotely comedic about the pamphlet, but it surely wasn’t the sort of trade the average person might need to call on! A quick search revealed that such business cards probably existed. Marwood acquired a reputation as an extremely efficient and capable executioner (much more so than his incompetent predecessor). He was very proud of skill as hangman, which makes the final line of “All orders promptly executed” possibly the darkest and most appropriate example of gallows humour I’ve ever come across.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply