April 7, 2014, by Kathryn Steenson

Money in Manuscripts & Special Collections

It’s not an anniversary many of us care to celebrate, but yesterday saw the start of the new tax year, and so it seems appropriate to post about some examples of historic money that we have in our holdings. Although we come across many unusual and surprising things when processing uncatalogued documents, it’s rare that we actually find money in an archive collection, which makes these documents all the more interesting. Occasionally old bank notes, cheques and other legal tender will be among the other papers, either hidden away for safekeeping and later forgotten about, or deliberately retained. These examples shown here fall into the latter category.

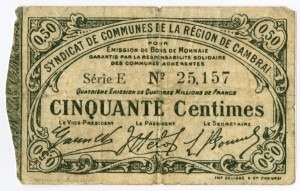

This is a billet de nécessité (Ref: Ln2/1/12/45), a temporary currency issued by French municipalities in World War One due to a shortage of normal currency. This one, with a value of 50 centimes, was issued by the Syndicat de communes de la région de Cambrai. It is undated but was probably printed around 1916. German troops occupied the town of Cambrai for much of the conflict. Local traders would accept the tokens in exchange for goods and services. Very few now survive as they were printed on extremely poor quality paper, and were generally destroyed after the war when they were no longer accepted as a form of payment. It was found with the papers of John Lawson (1878-1969), a Nottingham pharmacist and businessman who worked for Boots. His family’s archive reflects their interests in professional, religious and local political matters, although it is unclear from the surviving papers if or when John ever visited France.

This is a billet de nécessité (Ref: Ln2/1/12/45), a temporary currency issued by French municipalities in World War One due to a shortage of normal currency. This one, with a value of 50 centimes, was issued by the Syndicat de communes de la région de Cambrai. It is undated but was probably printed around 1916. German troops occupied the town of Cambrai for much of the conflict. Local traders would accept the tokens in exchange for goods and services. Very few now survive as they were printed on extremely poor quality paper, and were generally destroyed after the war when they were no longer accepted as a form of payment. It was found with the papers of John Lawson (1878-1969), a Nottingham pharmacist and businessman who worked for Boots. His family’s archive reflects their interests in professional, religious and local political matters, although it is unclear from the surviving papers if or when John ever visited France.

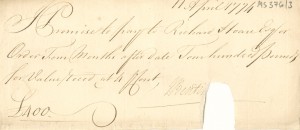

This 1774 promissory note (Ref: MS 376/3) from John A. Bentinck is for £400 payable to Richard Hoare Esq, of Hoare’s bank, presumably as repayment for a loan. It’s an unassuming-looking document that, at first glance, seems an unlikely ancestor of the elaborate, colourful and easily identifiable notes we use today. A promissory note is a written promise by one person to pay money to another. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries there were two main forms of promissory note: one which was payable to a named person, on or after a specific date, and one payable to the bearer, ‘on demand’. They often circulated without being cashed by a party, and from this the modern bank note evolved. Bank notes still contain the words ‘I promise to pay the bearer on demand the sum of…’.

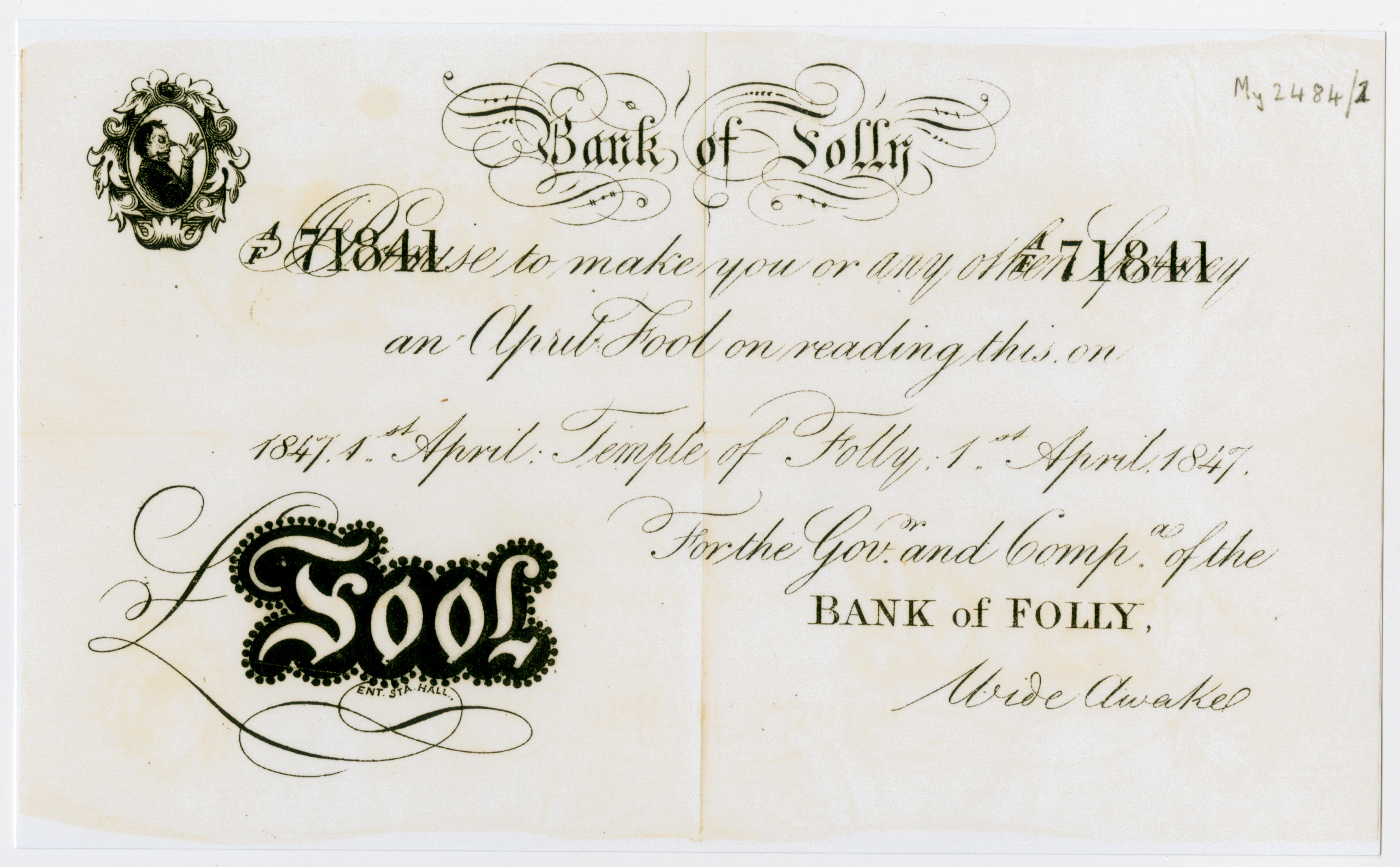

The third example (Ref: My 2484/1-3) was never legal currency. Some of you may have seen it posted on our Twitter account, @mssUniNott, for April Fools’ Day last week. It proved so popular that we couldn’t resist sharing it with those of you who missed it on Twitter. It’s an April Fools’ joke bank note from the ‘Bank of Folly’. In the top left corner, it depicts a man cocking a snook (thumbing his nose), and with the amount of money cleverly rendered as the word ‘Fool’.

The third example (Ref: My 2484/1-3) was never legal currency. Some of you may have seen it posted on our Twitter account, @mssUniNott, for April Fools’ Day last week. It proved so popular that we couldn’t resist sharing it with those of you who missed it on Twitter. It’s an April Fools’ joke bank note from the ‘Bank of Folly’. In the top left corner, it depicts a man cocking a snook (thumbing his nose), and with the amount of money cleverly rendered as the word ‘Fool’.

It reads, “I promise to make you or any other Spooney an April Fool on reading this on 1st April: Temple of Folly: 1st April 1847. For the Gov[ernor] and Comp[any] of the Bank of Folly, [signed] Wide Awake”. A ‘spooney’ or ‘spoony’ is an old-fashioned term for a foolish, silly person.

The note was found in the family and estate papers of Charles Brinsley Marlay of Westmeath, Ireland, which contains a rich source of correspondence between the aristocratic family members and prominent contemporaries.

All these collections are available to view in the Manuscripts and Special Collections Reading Room on King’s Meadow Campus.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply