October 25, 2013, by Kathryn Steenson

Cholera and Compassion in the Crimea

In the second of our posts marking the 160th anniversary of the Crimean War, we look at how although it achieved nothing in a geopolitical sense, the actions of one woman have undoubtedly touched the lives of millions of people. Very few people could name many of the battles the British Army fought in the Crimea, but most instantly recognise the name Florence Nightingale (1820-1910) as the nurse whose work in military field hospitals resulted in the birth of the modern nursing profession.

Shortly after the Crimean War began in 1853, reports appeared in British newspapers of inadequate medical facilities for injured and ill soldiers at the front. The Secretary at War, Sidney Herbert, was a close friend of Florence Nightingale and knew of her interest in nursing.

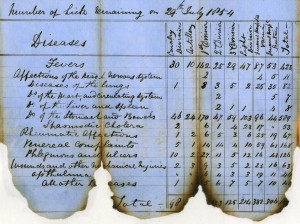

He arranged for Nightingale and the team of 38 volunteer nurses she had trained to go to Turkey and oversee the military hospitals. They arrived at Selimiye Barracks in Scutari (modern-day Üsküdar in Istanbul) in November 1854. The ‘Return of the Weekly state of the Sick of the Expeditionary Force from 23rd to 29th July 1854′ (Ref: Ne C 9833), dated just one month after the Expeditionary Force landed in Varna, Bulgaria shows how few soldiers suffered from injuries caused by battle, compared with disease. Of all the patients, most suffered from diseases of the stomach and bowels (e.g. dysentery) with 589 cases recorded; fevers at 429 cases; and 168 patients suffering with venereal diseases. Cholera was still the major killer, responsible for 112 of the 129 deaths in that one week in July.

The document is from the political and official correspondence of Henry Pelham-Clinton, 5th Duke of Newcastle under Lyne and Secretary of State for the Colonial Office and War Department, 1854-1855. It, and most of the other letters and statistical returns, suffered fire damage in the past, possibly in the fire at the Duke’s seat at Clumber Park in 1879. Although these figures are from a different area from that to which Nightingale was sent, the poor conditions and overworked medical staff were common to all military hospitals.

Nightingale’s reforms of patient care attracted some hostility from some medics and politicians, but the compassion shown to the soldiers won their support. Many of the tasks she and her nurses carried out, such as washing patients on arrival and always using separate cloths, and ensuring patients received adequate rations of soft, easily-digestible food, were considered rather revolutionary. Her routine of checking the wards at night earned her the nickname of the ‘Lady with the Lamp’.

Hand coloured printed illustration of wounded soldiers at a field hospital during the Crimean War, showing Florence Nightingale in a group of bystanders (Ref: Ms 95/1)

This copy of Jerry Barrett’s painting ‘The Mission of Mercy: Florence Nightingale receiving the Wounded at Scutari’ from 1857 (Ref: MS 95/1) shows how she captured the public’s imagination. The painting depicts a romanticised scene in a field hospital, with Florence Nightingale amongst a group of people gathered around an injured soldier. The annotations identify some of the people in it, including Dr Linton (Dr Sir William Linton, Deputy Inspector General of Hospitals of First Division of the Army in the Crimea), M. Soyer (Alexis Soyer, chef who advised the army on ways to improve cooking), Col. Sir Henry Storks (superintendant of the British bases during the Crimean War), Miss Tebbutt, Mrs Roberts, Mrs Moore (nurses), Col. Sillery, Dr Crookshank, Miss Nightingale, Mr and Mrs C.H. Bracebridge (Selina and Charles Bracebridge, close friends and supporters of Florence), and Lord William Paulet (Assistant Adjutant-General of the Cavalry Division in the Crimean War). The original painting is hanging in the National Portrait Gallery.

After the Crimean War, Nightingale returned to England and in 1860 she established the Nightingale Training School for nurses at St Thomas’s Hospital in London. She spent the rest of her life promoting nursing as a profession and advising on medical facilities. Numerous nursing schools, associations and a medal have been named in her honour (including The University of Nottingham’s very own Nightingale Hall of Residence). She wrote what was to become a classic introduction to nursing, Notes on Nursing (1859), and Notes on Hospitals (1860), both of which drew on her Crimean experiences and clearly lay out the statistical evidence that improved sanitation decreased mortality rates. This may seem obvious to us today, but before the germ theory of disease, her deduction that poor conditions led to disease did not have universal acceptance.

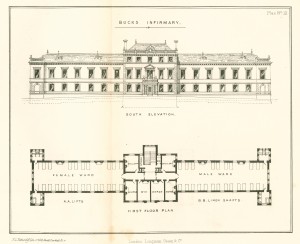

Plan of the south elevation and first floor of the Buckinghamshire Infirmary, by Mr. Brandon, drawn by F. G. Netherdift.

From ‘Notes on Hospitals’, by Florence Nightingale, 1863 (WX11.FE5 NIG)

This plan of Buckinghamshire Hospital from ‘Notes on Hospitals’ is an example of what Nightingale considered an ideal layout for the wards, with plenty of space, light and air. She opposed having curtains between the beds, as she felt they hindered ventilation and made for unnecessary washing, but championed providing decent, healthy meals, lamenting that so much care was taken over medicines yet the hospital kitchens were often staffed with people considered fit for no other work.

Within Special Collections, we hold the (very small) library of Florence Nightingale, consisting of books she and her family owned or had been given. The copy of ‘Notes on Hospitals’ by Florence Nightingale (King’s Meadow Campus Medical Rare Books WX11.FE5 NIG) is part of the Medical Rare Books collection of 400 volumes dating from 1580 to the 20th century.

For more information about the resources we hold about the Crimean War in general, please see our previous blog post. All these documents and books are available for consultation in the Manuscripts and Special Collections Reading Room on King’s Meadow Campus.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply