November 1, 2017, by Jake Hodder

Black History Month 2017

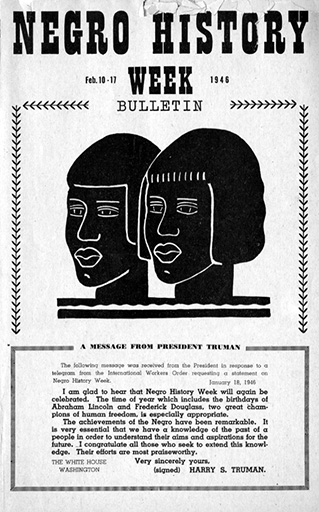

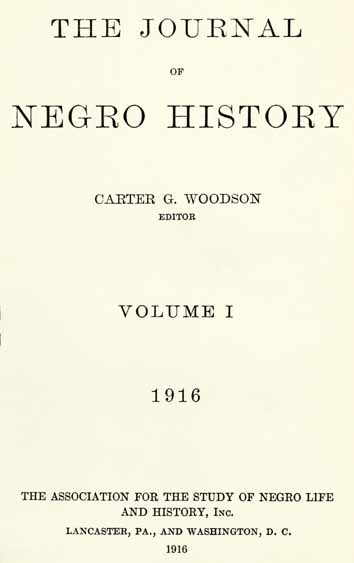

Black History Month was established as Negro History Week in 1926 by Carter G. Woodson, widely known as the ‘Father of Black History’. Woodson had established the Association for the Study of Negro History and Life (ASNLH) in 1915 and, the following year, launched its widely respected Journal of Negro History a year later in 1916. Negro History Week was the centrepiece of Woodson’s varied attempts to popularise Black history in the first half of the twentieth century. As part of an ambitious programme of outreach and engagement, Woodson sent teachers packs to schools over the length and breadth of the USA in order to bring the latest in academic scholarship to school children. Ninety years on that same commitment continues to underpin Black History Month and, in Woodson’s spirit, we were keen to see how our own research could be put to use in Nottingham’s schools to help develop today’s Black history programme.

Negro History Week was originally established to run in the second week of February, a week specifically chosen to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln (February 12th) and Frederick Douglass (February 14th) – two of the most celebrated figures of black history. Today, the greatly expanded Black History Month stretches over the entire month of February in the USA, and over the month of October in the UK (one of a number of differences between its US and UK varieties). Whilst in the United States Black History Month has increasingly focused on the achievements and challenges of the African American experience specifically, whereas in the UK there tends to be a broader focus on African, Caribbean and even Asian history.

In the US this focus on African Americans is a significant shift from even Woodson’s initial conception of Black history, long premised on African Americans ‘reconnecting’ with the wider Black diaspora in Africa and the West Indies. This emphasis can be found in any number of Woodson’s projects and writings: it’s embodied in his unfinished Encyclopaedia Africana (drafts of which can be found in his papers at the Library of Congress), and elucidated in some of his major texts including The African Background Outlined: Or, Handbook for the Study of the Negro (1936) or his far better known The Miseducation of the Negro (1933). In fact, Woodson through ASNLH, the Journal of Negro History and Negro History Week arguably did more than anyone else in popularising the history and culture of Africa and the wider black world to African American audiences who had, up until then, tended to view the continent negatively.

For these reasons and others, I was especially interested in seeing how some of the ideas we have been developing in the AHRC grant, especially around Pan-Africanism and the meetings of the Pan-African Congress in the 1920s, might be used in schools.

This opened a space to reconnect with Woodson’s initial vision, and also develop a range of new sources to augment current teaching packs which are largely drawn from the Black experience in America – which in most cases means the civil rights era (Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr, etc.). This limited focus was a repeated concern mentioned to me by teachers who have long sought a more diverse range of Black history teaching materials, historically and geographically, which they believed would better connect with the unique backgrounds of their own students.

This was certainly the case with the primary school I recently worked with in Nottingham’s Hyson Green, a neighbourhood with the largest ethnic minority population in the city. Whilst Hyson Green’s own black history is extraordinarily rich, the previous year’s focus had been Rosa Parks, and Martin Luther King Jr the year before that. As a majority non-white school, however, with a diverse cohort of students from Poland to Eritrea; Italy to Ghana, they hoped for a wider focus for this year’s activities.

We created a new teaching programme which included materials for a half-hour assembly, and two separate hour-long workshops, one aimed at younger students, and one older (each of which ran twice).

The focus of the assembly and lessons was on Marcus Garvey, one of the leading Pan-African figures of the 1920s. Born in Jamaica, Garvey spent some of his most significant years in New York City running the wildly popular Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Garvey was deported from the USA in 1927 and he spent the remainder of his life travelling extensively, including to the League of Nations in Geneva where he famously put forward his “Petition of the Negro Race”. He died in London in 1940.

Despite Garvey being one of the most memorialised figures of black history, including any number of eponymous parks, universities, and other civic buildings around the world (including Nottingham’s own Marcus Garvey Centre), there is remarkably little material available to teachers designed to help introduce Garvey and the significance of his ideas.

We started the day with a school-wide assembly outlining the significance of Black history, why Garvey was an important figure within it and how his ideas continue to matter. Chief among them was importance he placed on Black history itself to notions identity and self-worth, famously writing “A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots.”

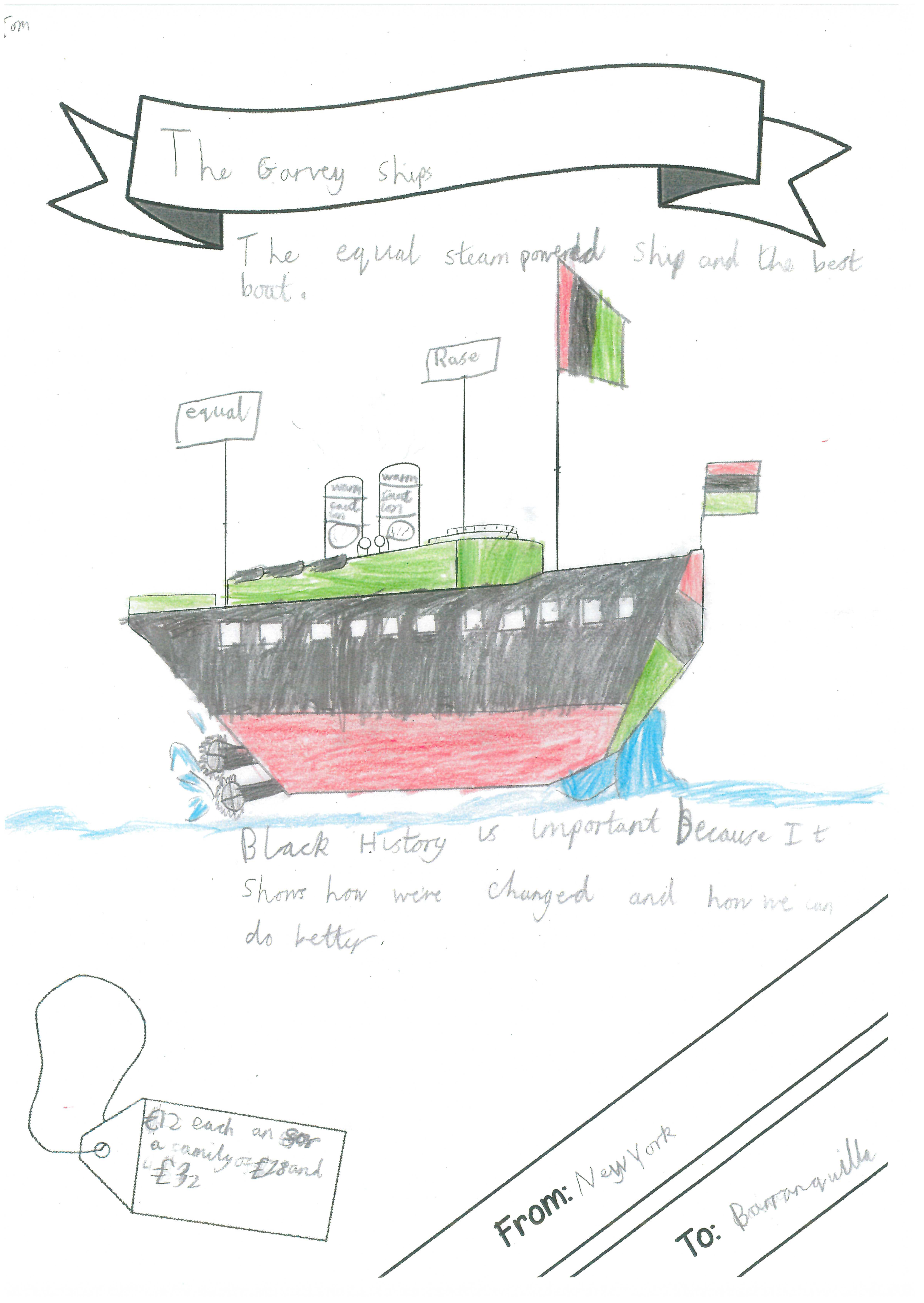

After the assembly I did four one-hour workshops with a class from each year group (aged 7 – 11). The first workshops (ages 7-9) involved a short introduction to Garvey’s steamship company, the ‘Black Star Line’, followed by students creating an advertisement using a preformed template. Students had to devise a name for their shipping company, make the advertisement bright and colourful, list a price, and use their atlas’ to find a city on the coast to which their ship would sail. They also had to write a sentence or two about ‘why black history is important’ and draw Garvey’s famous Pan-African flag. At the end of the lesson we discussed the significance of the black star on the flags of Ghana or Guinea-Bissau (symbolically representing Garvey’s Black Star Line) and of Garvey’s Pan-African colours on flags such as Malawi or Kenya.

The second workshop, undertaken with older students (ages 9-11) involved working in pairs to create a newspaper on an A3 template. The newspaper had four elements – i) a map of Africa and Pan-African flag to complete using atlases, ii) an advertisement for a Black-run bank, iii) an advertisement for Garvey’s shipping company and iv) a letter, written by Garvey, to readers about the importance of Black history. A template was given for each of these elements on separate A4 sheets, which were then cut and glued onto the newspaper. Afterwards we spoke about the significance of Garvey’s own newspaper, Negro World, as well as the importance it placed on Africa historically and culturally.

The aims of both of these workshops was to create activities that would encourage students to think critically about the past. They sought to draw on new scholarship, including some of the insights from this research, which has shown the importance of understanding Pan-Africanism not simply as a political project, but one in which social, cultural, artistic and intellectual elements combined.

These ‘enrichment’ lessons blended together history, geography and literacy skills with a number of broader questions about citizenship, racial justice, and how we deal with difficult pasts. It raises important questions of what kinds of stories geography can tell, who tells them, and who is left out? Like Woodson wrote of history, so too is geography a subject haunted by the absence of black perspectives. Ironic for a discipline founded on the exploration of Africa, it paid so little regard to its people, history or culture. As Jonathan Swift famously quipped, “So Geographers in Afric-maps, With savage-pictures fill their gaps; And o’er uninhabitable downs, place elephants for want of towns.” Interventions like those above may be small, but they open an important space to conceive of a different kind of geography. A geography that is for everyone. Rather than memorizing cities on a map, these students explored their own geographies – a sense of place and belonging as personal and as powerfully felt as the sense we instinctively have of our histories and past. Together these are two of the most elementary and yet difficult questions we all confront: who am I and where am I from?

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply