April 1, 2017, by Stephen Legg

A Princely Archive: The Ganga Singh Memorial Trust records, Bikaner, Rajasthan, India

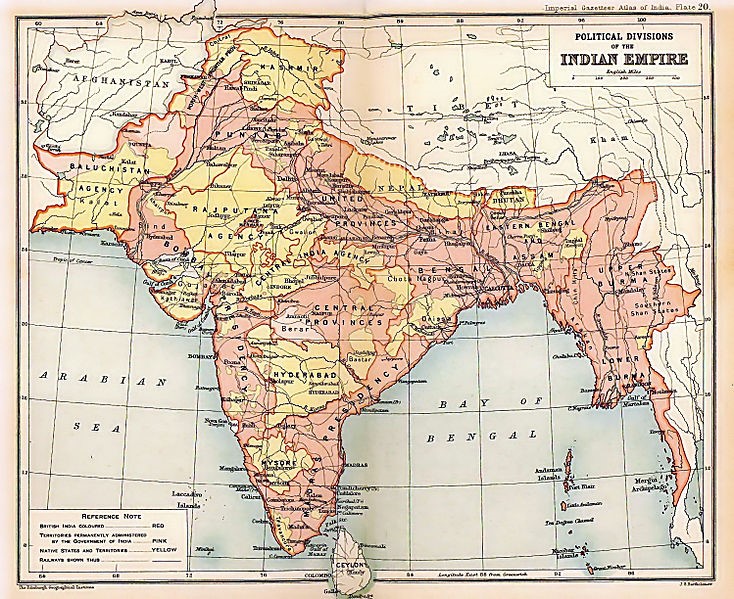

The nation state monopolises many official archives. These include archives at the level of the nation (the National Archives of India, in New Delhi, or the UK in Kew, London), but also at subsidiary levels (the Scottish National Archives in Ediburgh, the Bengal archives in Kolkata, the Nottinghamshire County archives in Nottingham). Conferencing the International argues that internationalism mostly lacks archives of its own, and that interwar conferences formed a dispersed archive of 1920-30s internationalism. There are exceptions and anomalies, of course. The League of Nations has its own archives in Geneva, which exist in contexts both national (Swiss) and international (they are housed in UN property). For colonial India, the Princely States mark another exception. They were part of the Indian Empire and expressed loyalty to the Viceroy as “paramount power”, but they were legally and geographically distinct from “British India” (British provinces are marked here in pink, being those territories controlled by the East India Company by 1857).

Political Divisions of the British Empire, Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:British_Indian_Empire_1909_Imperial_Gazetteer_of_India.jpg

The yellow “Princely States” numbered 562 in 1929, and ranged from vast to small, being led by Maharaja’s, Rajas, Nizams and other hereditary rulers. Having been guaranteed their rights in the “Victoria Proclamation” of 1858, they had been loyal to the Crown in the First World War and had mostly remained so in the face of rising anti-colonial nationalism. The 1919 Dyarchy reforms had applied only to British India and had left the Princes untouched, although many were modernising of their own accord (as argued in Janaki Nair’s Mysore Modern). However, the Indian Statutory Commission’s investigation into the working of dyarchy in British India (the “Simon Commission”) was being paralleled in the late 1920s by the Butler Commission into the Princely States. One of the chief justifications for the Round Table Conferences was that they needed to consider both the Simon and Butler reports together. That is, to consider India as a constitutional whole.

As such, when representatives of social and political India were invited to London, they constituted men (and a few women) from both British and Princely India. Whilst this had novel consequences for India internally, for decades India had been functioning as one unit diplomatically, as part of India’s International Anomaly. India’s emergence as an international unit had taken place in the late 19th and early 20th century at scientific and technical conferences (addressing postage, telegraph and shipping procedures) as well as at imperial diplomatic meetings. “India” had attended the Imperial Conference of 1917 and the Imperial War Cabinet of 1918, paving the way for its attendance at the Peace Conference of 1919 and its signing of the resulting Treaty of Versailles. Key to the latter had been the role of Maharaja Ganga Singh, of Bikaner. He had been at the 1917 and 1919 meetings, and featured prominently in representations of the Hall of Mirrors negotiations at Versailles as the only non-white member.

The signing of peace in the hall of mirrors, by William Orpen (1919), Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Signing_of_Peace_in_the_Hall_of_Mirrors_(fragment).png

Ganga Singh embodied the aristocratic bond between the royal lines of Britain and India. He was King George V’s aide-de-camp from 1902 and had taken care of the Prince of Wales during his 1921 tour of India. He had publicly professed his loyalty to the King in person during the Delhi Durbar of 1911, fought in the Middle East during the War, and maintained close personal contact with the King and Queen Mary while in London for the first two Round Table Conferences. The Maharaja was, however, anything but a Princely relic. He had introduced modernising reforms in his Rajput state, and transformed the tenor of the first conference when he came out, early, for Indian Federation. Cementing the idea of federating British and Princely India into one unit, his intervention was decisive in setting the agenda for the conference, and the next four years of debate over Federation, communal representation, and the sanctity of the Viceroy’s paramount and direct commitment to the Princes.

The National Archives of India house the files of the Home, Political, and various other departments. These include files on central policy but also record correspondence with provincial governments. Parallel but separate to these files are those of the Foreign & Political Department. “Foreign” here does not mean foreign policy as traditionally understood. “India’s” foreign affairs, up to 1935, were dealt with by the Secretary of State for India (in London) in correspondence with the Viceroy-in-Council. “Foreign” here refers to British India’s relation with those domestic units foreign to itself; the Princely States. While British Residents had influence on Princely policy, these “F&P” files retain a sense of externality.

Beyond Delhi, ex-Princely States have their own archives although they split to represent the divided sovereignty between the state and the Prince. Bikaner houses a branch of the Rajasthan State Archives (which are improbably listed as a tourist destination), but since 2005 the Maharaja Ganga Singh Ji Trust have also made the Maharaja’s files accessible to researchers. The records are explicitly not part of the national state apparatus but are stored at the Lallgarh Palace. The Palace was constructed between 1896 and 1902 by Ganga Singh and was designed by Sir Swinton Jacob, a colonial advocate of Indo-Saracenic architecture which blended architectural traditions from across India and beyond with more European flavoured interiors.

Whilst the grand south-west wing has been sold to a luxury hotel chain, the Ganga Singh Ji Trust runs other wings of the palace as a hotel with direct connections to the royal family (photos of past and present family members are placed throughout).

The compound also includes an impressive museum detailing the strong connections between the Singh line, the rulers of British India, and the British aristocracy. The records room was modest but the “pads” (bundles) of files were meticulously ordered variously by department, period and event.

Fortunately for me, seven bundles had been preserved containing amazing materials, untouched since the 1930s, on the Round Table Conferences. The Maharajah was a famous host and his supporting staff filled file and after file composing invite lists for “at home” parties at the Carlton Hotel, as well as accepting or declining hundreds of offers for dinner, drinks or luncheon with leading London figures as well as various institutions with Indian affiliations (from the East India Association to the University of Newcastle Indian Students’ Union). Ganga Singh arrived in London exhausted after having represented India at the League of Nations in Geneva and then at the London Imperial Conference, but still had time for pre-conference networking to decide upon an agreed line between the Princes regarding Federation. He was also a committed and generous shopper, buying gifts for the King and Queen and his family at home, as well as fitting out Lallgarh Palace with reams of brocade, prints and furniture, much of which survives in the two hotels. 1930s London was clearly a multi-sensory consumption space for Bikaner, and his archives represent a tantalising glimpse into the intersection of culture and politics in an imperial conference city.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply