January 1, 2017, by Stephen Legg

The National Archives of India

The National Archives of India in New Delhi, like the British National Archives at Kew in London, turn government into History. Minutes, memoranda, laws, reports, and inter-governmental circulars, designed solely for the purpose of colonial bureaucracy, now become the stuff of history making; a dauntingly huge Imperial Archive. A substantial body of scholarship exists on the consequences of writing history using the materials compiled to create and enforce a colonial project. What is perhaps less often acknowledged is that all governments depend upon their own archives and their own history-tellings. All governments are always already making History to aid their successors in continuing their projects; as Jacques Derrida reminded us, the origins of the word “archive” are both arkhé, meaning order or government, and arkheion, being the home or dwelling of the Archon (ruler or magistrate) where documents were stored.

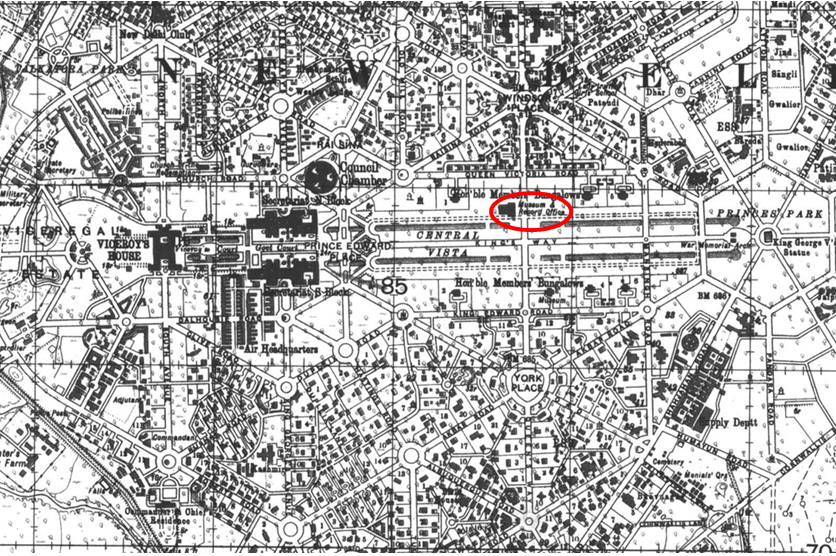

That all governments both make and store their own history was readily apparent to the Empire of the British in India. By the twentieth century the English, later the British, had spent 300 years usurping and forcibly acquiring sovereign territories in the subcontinent, with each accession having its history, traditions and protocols absorbed and only part-standardised into the Raj. Each anomaly within this empire of anomalies had to be recorded and known. With the creation of the capital, New Delhi became the memory space in which this information would be deposited. Perhaps for reasons of restricted space on Raisina Hall (home of the Indian Civil Service) these documents did not sit within Secretariat. But they still had pride of place at the geometric core of the city, where Kingsway (now Rajpath) met Queensway (Janpath) (see image above).

The Records Office was one of the relatively few buildings designed by Edwin Lutyens himself (the others including the Viceregal House and India Gate, above). It lacked the Eastern proportions and motifs of the Viceroy’s House but not his imperial symbology or mischievousness. For New Delhi Lutyens had designed a new “Delhi order” column capital, incorporating stone bells, alluding to the myth that that the ringing of bells in the region signalled the end of yet another Empire that had made Delhi its capital. Calcified in stone on both the Viceroy’s House and the Imperial Records the bells would never ring, forestalling history into an eternal imperial present (below). Sixteen years after the capital was inaugurated in 1931, the bells tolled and history arrived for the British in India.

The Imperial Records became the National Archives. The relatively small reading room became unable to satisfy the demand for historical materials so the files are now stored in an annex which replicates the standard modernism of the other ministry buildings that had been built down Rajpath. Generations of South Asia scholars have served their time in the basement of Annex C, deprived of natural light but revelling in the icy air conditioning and some of the richest archival materials on the planet.

The National Archives had just finished celebrating their 125th anniversary when I visited in the spring of 2016. The archives themselves now have their own museum exhibit (which was closed) and the much neglected original reading room, which had lain abandoned and derelict for years, has been restored and is now open as an official publications reading room (see below). Here sit the published records of Legislative Assembly Debates over the Round Table Conferences, their cost, their delegates, their constitutional proposals, and the raking over of the Government of India Act (1935) that resulted.

The National Archives resides somewhere between the state and the nation. Access to the archives is sanctioned by the Home Ministry, within whose remit the archives exist. Securing a pass to enter the site at weekends has to be approved by the Ministry. Applications can take three to four weeks to process by the government, which is at present run by the BJP, who ousted the Congress party in 2014. However, on entering the National Archives, which houses documents and private collections addressing all manner of social and political histories, one is immediately faced by the “Bapu Collection” room, featuring stacks of books on Gandhi and his legacy. Perhaps for balance, to the left sits a new bust of Suhbas Chandra Bose, a Congress leader who later rejected the party and, with Axis support, raised the Indian National Army in Japanese occupied Singapore and launched a (failed) attempt to invade India and wrestle it from the British during the Second World War. It’s a very busy entrance, and reminds the researcher (as if a reminder was needed in such a location) that in writing history in New Delhi, the colonial state and the postcolonial nation is never far away.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply