June 15, 2018, by Harry Cocks

Why the Reformation(s) were Nothing Like Brexit

The recent 500th anniversary of the Lutheran Reformation of 1517 prompted a series of articles in the press seeking historical parallels between Henry VIII’s Reformation of 1532-4 and Brexit. The superficial similarities – England deciding to leave the jurisdiction of a supposedly corrupt and self-interested European superstate (the papacy) – appealed to lazy journalists looking for a headline. Very few of them bothered to listen to those historians who pointed out that the Protestant Reformation (we should in any case talk of Reformations – Lutheran, Calvinist, Catholic; Henrician, Edwardian, Marian, Elizabethan, Jacobean) was in fact a European phenomenon that transcended national borders and aimed to establish a universal church of the true faithful. In that respect, English Protestants aimed not to separate from Europe but to join with their cousins on the European mainland in a community of true believers who were united in their efforts to resist the papal Antichrist.

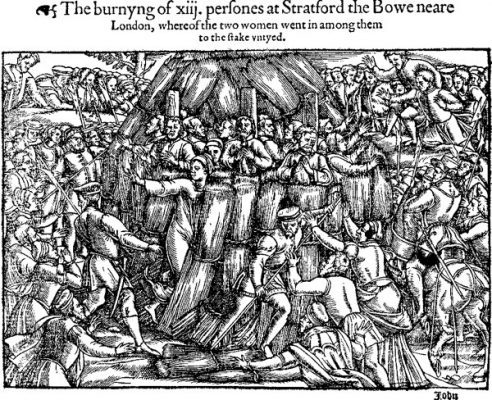

A new article by David Gehring of Nottingham History and Thomas S. Freeman (see link) shows just how important this European context was to English Protestants by examining the ways in which the celebrated English martyrologist, John Foxe, drew on European sources for his Actes and Monuments (1563, and better known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs). For a long time Foxe’s work was seen by some as a truly ‘English’ argument for a national Church, earning him the status of a proto-nationalist. To take one example from the Book of Martyrs, Foxe recorded the death of the German priest Johann Heuglin, who died in the early 1520s, in the following way: ‘the bishop of Constance caused a certain priest, named John Howgly to be burned at Merspurge, for that he would not allow the bishop of Romes doctrine in al poyntes.’ This was only one of many accounts of continental martyrdom that Foxe recorded. But where did he get his knowledge of these cases from? Gehring and Freeman show that Foxe was deeply embedded in the historical and matyrological literature coming from the mainland, and that he was particularly reliant on the Swiss polymath Heinrich Pantaleon’s Martyrum Historia (1563). Panteleon’s book compiled the accounts of persecution from other sources, such as those by Ludwig Rabus and Adriaan van Haemstede, thereby making these earlier histories of persecution available to Foxe and to English readers. In addition, Pantaleon could read German, French and Dutch, and was therefore able to use a wide range of vernacular literature that was not available to other martyrologists less able in other languages. Foxe then used Pantaleon’s work to give his own Book of Martyrs a wider European focus, and to draw direct connections between English martyrs and their confessional brethren.

Although Foxe is often seen as progenitor of English nationalism, his vision of Protestantism was that of a universal Church, and, as the authors conclude, ‘his unflagging efforts were bent towards seeing that his compatriots could learn about, and draw inspiration from, their co-religionists of the True Church who lived and died on the European mainland.’ Equally, without Pantaleon’s martyrology, Foxe’s Acts and Monuments would have been a record of Protestant martyrs in England, Scotland and France, with scattered additions from the Low Countries and Spain. Foxe was able to use Pantaleon’s work as a ladder from which he could reach the texts of Rabus, Haemstede and others. As a result, English Protestants could see themselves as one part of the True Church, which had had members across the world in every age since the time of Christ.

David Gehring and Thomas S. Freeman, “Martyrologists without Boundaries: The Collaboration of John Foxe and Heinrich Pantaleon,” Journal of Ecclesiastical History (2018)

“was in fact a European phenomenon that transcended national borders and aimed to establish a universal church of the true faithful. In that respect, English Protestants aimed not to separate from Europe but to join with their cousins on the European mainland in a community of true believers who were united in their efforts to resist the papal Antichrist.”

So just like nationalists across Europe working to smash the EU and the globalists and establish a community of sovereign nation states.

Like most Brexiters, I think you missed the point – Protestantism was a universal vision that transcended national borders. Maybe read the article?