January 8, 2015, by Harry Cocks

American Labour and the Great War

In 1917, claimed President Woodrow Wilson, the United States entered the First World War to ‘make the world safe for democracy.’ On that proposition hundreds of thousands of American soldiers left for the trenches of Belgium and France. At home, however, an equally bitter series of struggles took place over whether democracy would also arrive in the factories, workshops, mines, mills and offices of the US. Employers hoped to curtail the growth of organised labour. Trade unionists hoped that, at the very least, they might expand into hitherto unorganised industries and secure more rights at the workplace. Both fought over how, and by whom, industry would be run. They conducted these struggles in unusual wartime conditions. Unemployment approached zero, inflation spiralled into double figures, and disputes over wages and working conditions broke out in rapid succession all over the country. More than three thousand recorded strikes broke out in the six months that followed the American declaration of war, more than in all of the previous year, and more than in any previous chapter of American history. In November 1917, the Bolshevik Revolution knocked Russia out of the war and raised the prospect of revolution, not just strikes, in the US itself. In this dangerous and promising situation for the various sides, President Wilson and his Administration led the first sustained foray by the federal government into the field of labour relations. The war for democracy – and much else besides – was fought in the United States as well as in Europe.

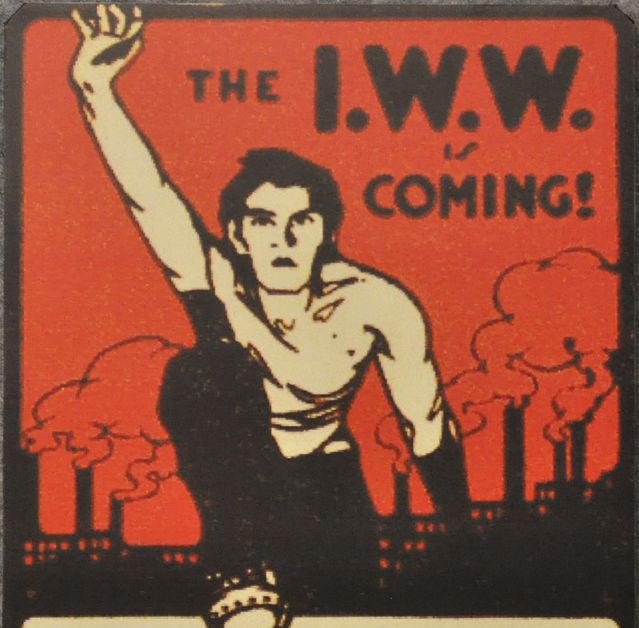

In three new articles, Steven Parfitt, a recent history Ph.D here at Nottingham, deals with various aspects of these struggles on the home front. The first two, “Democracies in Conflict” and “Whither Industrial Democracy,” look at the experiences of machinists in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and telegraphers with the Western Union Telegraph Company, respectively. In each case a union, affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), negotiated not only with management but with a number of governmental bodies. Machinists in Bridgeport, organised in the International Association of Machinists, found their struggles with employers over wages, deskilling and piece-work wages governed by the National War Labor Board (NWLB), the pre-eminent federal agency that dealt with labour disputes during the war years. The telegraphers, some of whom were organised in the Commercial Telegraphers’ Union of America, firstly encountered the NWLB and were then put under direct federal administration. The third article, by contrast, deals with a radical movement, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Where federal administrators attempted to mediate conflict between employers and AFL unions, they practised unrelenting repression when it came to the IWW. My article deals with the mass surveillance and censorship of the IWW and the mass trials of nearly 200 leaders in 1917 and 1918. Their repression is particularly relevant today as the legislation under which they were prosecuted, the 1917 Espionage Act, remains the key legal weapon that the Obama Administration uses to prosecute leakers and whistleblowers.

Taken together, these three articles provide a more pessimistic account of the effect that wartime had on the American labour movement than most recent treatments of the subject. Work by Joseph McCartin and Melvyn Dubofsky, amongst others, tend to focus on the gains that unions made through federal intervention, including more members and greater representation at the workplace, and less on the repressive aspects of federal policy or the role that federal interventions had on conflicts within the labour movement. My articles tend, by contrast, to emphasise the repressive aspects of federal labour policy, whether directed against the IWW or, in the case of unions affiliated with the AFL, I emphasise that federal intervention could often promote anti-union or non-union policies as well as protect unions and trade unionists from employers. These articles help us to further complicate and deepen our understanding of American labour’s experiences during the years of the First World War. They also provide another reminder that, amidst our commemorations of the slaughter fields of Ypres, the Somme, the Marne and elsewhere, the war was a time of social conflict at home as well as of military struggles in the trenches of Belgium and France.

“Whither Industrial Democracy? The Federal Government and Organized Labour in the Telegraph Industry During the First World War,” Journal of American Studies 48:2 (2014), pp. 517-39.

“Democracies in Conflict: Union Democracy, Industrial Democracy, and Machinists in Bridgeport, Connecticut during the First World War,” Historical Studies in Industrial Relations 34 (2013), pp. 83-110.

http://liverpool.metapress.com/content/07761q33m0u311u0/

“Bringing the IWW Back In: Industrial Democracy and the Repression of Radicalism in the United States During the First World War,” Socialist History, to be published in volume 46 (2015).

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply