November 4, 2013, by Harry Cocks

The Knights of Labor: An International Perspective

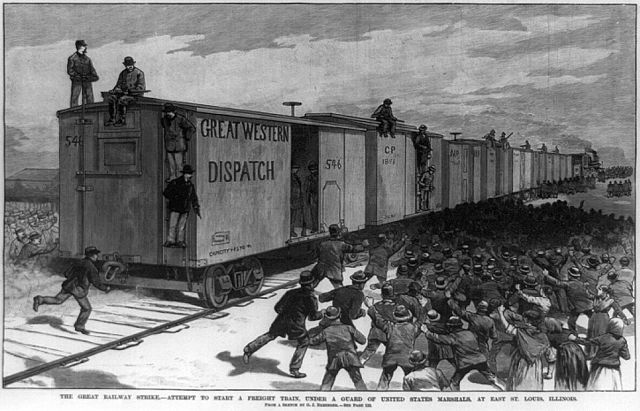

The Order of the Knights of Labor was the largest and most powerful organisation of American workers in the nineteenth century. Created by seven Philadelphian tailors in 1869, it was based on the fraternal practices and rituals of artisanal workers and secret societies such as the Freemasons. By 1886 the Knights and their assemblies, as they called their branches, stretched across Canada and America, reaching around a million members in the US alone. Their most notable battle (pictured above, from the Illustrated News) was in 1886 against the Southwestern railroad and its robber-baron boss Jay Gould, but the Knights also ran labour candidates that threatened to undermine the hegemony of the Democratic and Republican parties, and generally caused a great deal of apprehension amongst employers. From the end of that decade, however, the Knights fell into decline and in 1917, their once-mighty Order came to an ignoble end behind a leaky shed in Washington, DC.

Historians initially saw the Knights as essentially backward-looking, an attempt by artisanal workers pushed aside by factory production to wind the clock back to a mythical past of free and independent producers. Scholars in the past several decades have seriously undermined this picture, at least as it pertains to the United States and Canada. But in a new article for the International Review of Social History, Steven Parfitt, a Ph.D candidate in Nottingham University’s History Department, shows that there is much more to the Knights than their American activities. In England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Belgium, France, Italy, New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, and possibly Germany, Mexico and the Scandinavian countries as well, the Knights set up their assemblies. The global history of the Knights of Labor remains to be written.

Parfitt focuses not so much on what Knights achieved outside their home continent, but more on why they in fact decided to expand their Order across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Their brand of internationalism sprang from practical as well as idealistic sources. On the one hand, leading Knights professed their commitment to Universal Brotherhood – a term that could include women – and cast their overseas work as designed to bring the workers of all countries into one worldwide organisation that would replace capitalism with a political economy based on co-operative enterprise. On the other, American Knights feared the consequences for native workers of uncontrolled, mass immigration and sought to stem the tide of new arrivals by organising them in their home countries. The Knights practiced “brotherhood from a distance” – establishing the Order overseas to try to raise the wages, conditions and standards of workers elsewhere so that American workers would be saved from the negative consequences of mass immigration. They would extend a hand to workers elsewhere in the world and offer them aid so long as they fought their struggles – and stayed – at home. These contradictions, especially the racial and xenophobic tone employed, undercut the universality of the Knights’ idea of brotherhood. But this synthesis of idealism and concerns about immigration helped spread the Knights of Labor from North America to three other continents, a feat that no American labour organisation – except perhaps the Knights’ immediate successor, the Industrial Workers of the World (the “Wobblies”) – has surpassed before or since.

Steven Parfitt, ‘Brotherhood From a Distance: Americanization and the Internationalism of the Knights of Labor,’ International Review of Social History. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0020859013000187

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply