September 5, 2019, by lzzeb

Lung health and cookstoves in Nepal

A blog by Sarah Jewitt

During the past semester, I spent time investigating connections between the use of cookstoves fuelled with biomass (wood, charcoal, agricultural residue, dung etc.) and lung health in Nepal. This work was funded by an Institutional GCRF grant entitled Improving Respiratory Health in Nepal led by Ian Hall and Charlotte Bolton and involving collaboration between staff at the University of Nottingham (Schools of Medicine, Health Sciences, Engineering and Geography), Kathmandu University, Dhulikhel Hospital and ICIMOD. Working closely with Catrin Evans on qualitative aspects of the project, my contribution was focused on factors influencing the choice of household cooking systems and the extent to which local understandings of lung health are connected to smoke from cooking with biomass fuels.

Globally, biomass fuels are used for cooking by around 3 billion people and have been linked to chronic respiratory disease, childhood pneumonia and cancers as well to forest degradation and black carbon emissions (soot) that contribute to global warming. Women and children often suffer disproportionately as gender divisions of labour tend to give them greater responsibility for cooking and fuel gathering.

Efforts to encourage a shift to cleaner cooking systems have met with limited success as many rural communities have little knowledge of the health impacts associated with cooking smoke. When we asked local participants about the causes of respiratory problems, symptoms like coughing and shortness of breath were linked to dust from working in the fields as often as to cooking smoke or cigarette smoking.

Another barrier to the adoption of clean cooking systems is that biomass fuels are often available free of cost and clean fuels like LPG and electricity are expensive and – in more remote areas of Nepal – hard to access. Although a high proportion of Nepalis (91%) have electricity connections, frequent power outages make electricity an unreliable as well as an expensive cooking fuel. Obtaining LPG cylinders becomes more difficult with increasing distance from major urban centres; especially during the rainy season when poor road conditions make travel more arduous and dangerous. This was really brought home in a meeting at Dhulikhel Hospital where a representative from the accident and emergency department described a ‘mass casualty incident’ from the previous evening involving a tipper truck carrying over 50 people; most of them children. Following a period of heavy rain, the truck had slid off the road and down a steep hill causing a number of fatalities (the final number was yet to be determined) and many serious injuries. This incident, coupled with treacherous road conditions during heavy rain in areas of steep terrain highlighted the difficulties many remote Nepali rural communities face in transitioning to clean energy systems.

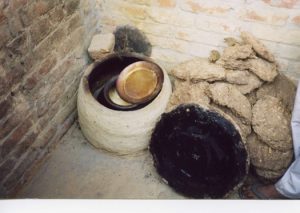

For cattle-owning households, biogas systems fuelled with dung (and human waste in the case of biogas sanitation) can provide clean cooking fuel as well as effective waste management along with digestate that can be used to fertilise homestead gardens.

As the volume of biogas produced is rarely sufficient to meet all cooking needs, most biogas plant owners continue to use their biomass stoves which reduces the respiratory benefits of cooking with biogas. Even families that do make a shift to LPG or electric stoves often retain their biomass stoves as a source of space heating in winter or for particular cooking tasks such as brewing alcohol, slow-cooking milk-based desserts and preparing food for cultural events.

Many Nepali smallholders also have a separate (often very inefficient and smoky) biomass-fuelled stove that they use to cook food for their animals. Despite having worked quite extensively in South Asia, I had not come across this practice before.

Intrigued by the idea of ‘cooking for cows’, I am currently working with colleagues at Nottingham and Kathmandu Universities to explore the suitability and acceptability of a more efficient and cleaner burning biomass stove for this purpose.

This research builds on a pilot study supported by Live to Love International using a top-loading down-draft gasifier designed by Ben Robinson; currently a PhD student in Engineering supervised by Mike Clifford and myself. Feedback obtained from the pilot study participants (some of which was collected by Joe Hewitt) included positive comments from cattle-owning stove users who had made significant time and financial savings as a result of the stove’s greater fuel efficiency. For more information, check out @escap_aid and @nepallungGCRF.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply