September 4, 2019, by lzzeb

Coal, cotton and the value of local fieldwork

In this blog David Beckingham discusses the tradition of local research and fieldwork in the School of Geography, using as his examples sites from day one of the walk from Nottingham to Malham.

Fieldwork is an essential part of any geography degree, often valued because it helps us see the world we want to understand at first hand. These experiences offer a different way of learning, away from textbooks and the lecture theatre, but vitally important too is the development of skills of data collection and analysis.

In the 1930s Nottingham lecturer K.C. (Kenneth Charles) Edwards was ‘in the forefront of those geographers who were actively promoting field studies and making them an integral part of academic training’, developing a range of local and European ‘field camps’ [1]. That training – which today might range from learning how to conduct interviews or retrieve archival information, take soil samples or measure water quality – also equips geography graduates for a world of work beyond University research.

Teaching through fieldwork can also help develop an important ethical concern that reaches beyond the processes we might be studying to consider what it means to research and work in a place. Edwards’ local commitment, for example, bore fruit in 1962 in a volume of the New Naturalist series devoted to The Peak District, with contributions on geology from the former head of the Department H.H. Swinnerton. It was also seen outside of the University, where Edwards supported the work of the Ramblers’ Federation and the Youth Hostels Association and assisted the Nottinghamshire Footpaths Preservation Society to plot rights of way on six-inch scale maps [3].

It is fitting that our Resource Centre – which houses our archive (including records of early field courses) and extensive map collection – is named after Edwards. These maps, many clearly acquired to support field teaching, can be used to trace the route from Nottingham to Malham that colleagues will be walking as well as track historical landscape change. Beginning in University Park, day one’s route moves through nearby Wollaton Park and west to the Derwent Valley in Derbyshire. These sites are connected as the subject of historical and cultural landscape research and fieldwork in the School.

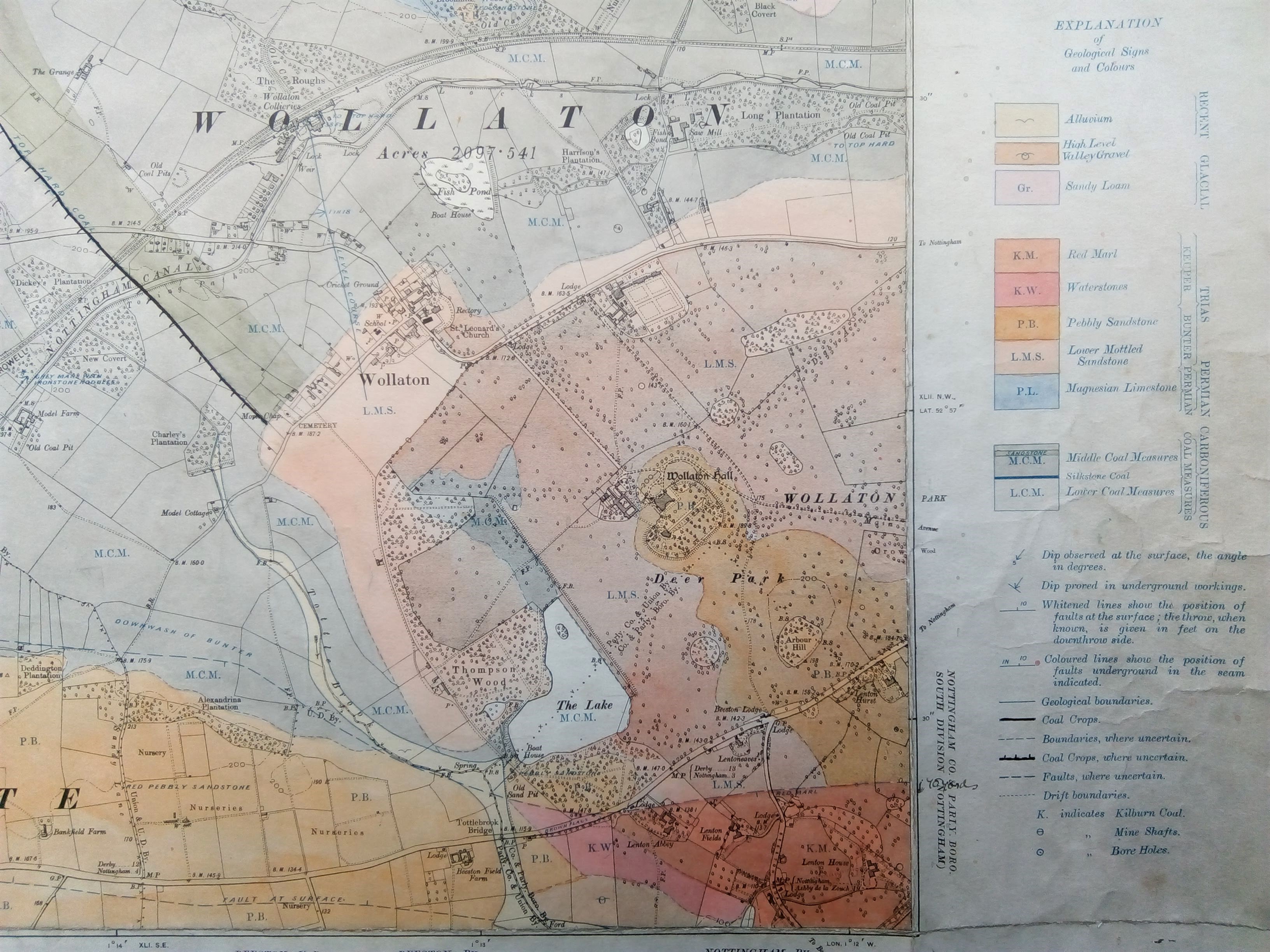

Wollaton Hall was commissioned in the 1580s by Sir Francis Willoughby, a wealthy land and coal mine owner who is credited as being the first industrialist to build a large scale house of this kind. The Hall and the subterranean source of much local wealth can be seen on the 1901 Geological Survey map of the area. Wollaton’s rich architectural and landscape histories were the subject of a special report to support the funding and conservation efforts of the Hall’s current owners, Nottingham City Council, by members of the School Stephen Daniels, Charles Watkins and Phil Kinsman [3]. Their work deconstructed how changing tastes reshaped the world above ground, built on the profits of mining labour unseen and even unimaginable to the casual visitor.

Figure 1 (main image), Wollaton below ground (Ordnance Survey, Geological Survey of England and Wales Second Edition, Nottinghamshire Sheet 41 NE, six inches to one mile, 1901, School of Geography Map Collection)

These sorts of connections between land and labour form the basis of first year tutorial field trips to the Park, and were previously also used in third year teaching. The estate’s records – held in the University’s Manuscripts and Special Collections – are also an essential part of our second year human geography methods training. By stepping out of the classroom it is possible to introduce students to major themes of historical and cultural research, examining the relationship between the paper archive and the changing material landscape around us.

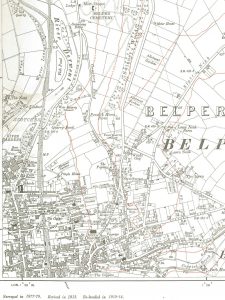

Day one ends in the Derwent Valley, north of Derby. The Valley was the heart of Richard Arkwright’s cotton-spinning empire, a technological and industrial powerhouse and vital laboratory for economic organisation in factory boom-town Britain. Just as the Wollaton wealth was intimately connected to labour that might not be widely seen, so too was the raw material for the mills of Cromford and Belper – much of which continued to be produced by enslaved African labour in the Americas even after Britain had formally abolished slavery in its colonies. It is that global reach, pulling the products of plantation labour right into the heart of Derbyshire, now part of a World Heritage Site, which has been the special interest of Susanne Seymour.

Figure 2, The cotton mills of Belper beside the River Derwent and railway line to Derby (Ordnance Survey, Derbyshire Sheet 40 SW, six inches to one mile, 1921, School of Geography Map Collection)

Across related collaborative projects Susanne Seymour has analysed industrialists’ personal and professional attitudes to slavery and its abolition, and the changing means of producing their precious raw material [4]. Tracing such connections helps us appreciate a more global historical geography of these otherwise archetypally British industrial landscapes, and through that, even, a more intimate understanding of the way sometimes seemingly disconnected individual lives made these places.

Visiting such sites – as students do on a third year fieldtrip for the Cultural Geography of the English Landscape module – provides an opportunity to analyse whose histories are remembered in places such as Belper and Cromford, and therefore examine what is counted as heritage. Rather than simply seeing the world at first hand, then, fieldwork is important because it can draw attention to what is hidden in and by these landscapes. And the effects of such work can be even more powerful when we consider the places on our doorstep, those we know well and value and those we maybe otherwise overlook.

[1] K.C. Edwards (1962) The New Naturalist: The Peak District (London: Collins)

[2] R.H. Osborne, F.A. Barnes and J.C. Doornkamp, ‘Foreword’, (1970) in R.H. Osborne, F.A. Barnes and J.C. Doornkamp (eds.) Geographical Essays in Honour of K.C. Edwards (department of Geography: University of Nottingham) page viii

[3] S. Daniels, C. Watkins and P. Kinsman (1999) The Landscape of Wollaton Park: Cultures of Nature (Nottingham: School of Geography)

[4] S. Seymour (2016) ‘Publication on the historic global connections of cotton in the Derwent Valley mills’, blogpost: https://globalcottonconnections.wordpress.com/author/susanneseymour/. And see S. Seymour, L. Jones and J. Feuer-Cotter (2015) ‘The global connections of cotton in the Derwent Valley mills in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries’, in C. Wrigley (ed.) The Industrial Revolution: Cromford, The Derwent Valley and the Wider World (The Arkwright Society: Matlock) 150-70

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply