May 31, 2018, by lzzeb

Race, ‘resilience’, and resistance: reflections on the AAG 2018

A blog by Dr Nick Clare

There is no such thing as a natural disaster. When visiting New Orleans it is impossible not to be confronted by this. As Dr David Beckingham outlined in his blog critical, historical reflection is required to understand the contemporary city; a city shaped by complex histories of colonialism and slavery, but also by resistance. The legacies of Katrina are no different, being highly contested and uneven. Visiting New Orleans for the 2018 AAG conference provided a snapshot of these legacies, reinforcing the need for urban geographies that take the intersections between race, class, gender, and the environment seriously.

Resilient NOLA

On my first full day in New Orleans I attended a fascinating ‘work day’ with friends and colleagues from The University of Sheffield’s Urban Institute . The day began with a visit to City Hall to discuss New Orleans’ ‘Resilient NOLA’ plan which emphasises environmental and social change through the use of new systems and technology. The challenges they face were obvious, with funding often tied to flashier, more eye-catching projects, leaving them unable to deal with the 40-year backlog of much-needed street repairs, contributing to New Orleans’ infamous potholes.

The resilience strategy itself is an interesting example of ‘knowledge transfer’, drawing heavily on work with researchers and planners from Medellin and Rotterdam, and since exporting its expertise to help with flooding in Houston and Puerto Rico. While Katrina was of course at the heart of the discussion, the member of City Hall resisted placing all the blame on the disaster. They described it as a momentous ‘rupture’, but not the root cause of anything, pointing instead to the centuries of urban ‘planning’ that reflected and amplified racial and class-based inequalities. Central to the resilience plan, therefore, is the desire to ‘not rebuild NOLA as she was, but as she should have been’. But while this ambition to avoid reproducing a grotesquely unequal city is important, it, and the wider discussion of ‘resilience’ was met with suspicion and even anger by community activists.

ACORN, the Lower 9th, and Justice and Beyond

The second part of the day was spent with a range of community organisers and activists, beginning with members of ACORN[1] (Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now) who were involved with the immediate post-Katrina relief effort. The horror of the disaster was made clear, with well over 1000 deaths, 100,000 people permanently displaced, and many bodies still unidentified.

These vast figures were made all the more real when we visited the Lower 9th ward. Famously the worst hit by Katrina, this working-class, predominantly African-American neighbourhood truly encapsulates the idea that there is no such thing as a natural disaster. The Lower 9th flooded because of failures to the federally built levee system, failures that would not have happened had the area been rich and/or white.

The ACORN members explained how this racial inequality carried over into the recovery process. People were told not to come back, disaster relief money was embezzled, and the schools were closed for two years. This issue of schooling was mentioned repeatedly, often described as a process of ‘bleaching’ – when the schools re-opened they did so as charter schools with predominantly white staff. These racially-charged educational inequalities have had far-reaching consequences, with the generation most affected now young adults, and this lack of education being directly linked to New Orleans having the highest murder rate in the USA. So while social issues therefore always shape ‘natural’ disasters, it is vital to look at how ‘natural’ disasters shape and exacerbate social issues.

The centrality of the bottom-up, community response to Katrina was made clear. House after house, block after block, the ACORN members pointed out examples where they had repaired and rebuilt people’s houses and lives – often with no support at all from the state. But alongside all these examples, in the shape of empty and overgrown plots, was the constant reminder of the lives lost and the families that could never return. For those in the Lower 9th, Katrina was not something that has happened, but something that is happening every day.

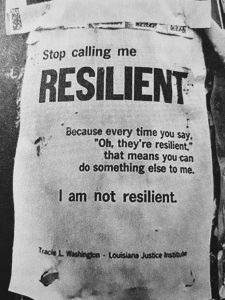

We visited the ACORN community garden, an example of the ‘place-based resilience’ so central to the discussion of that morning. As the discussion shifted to our experiences earlier in the day, the animosity to resilience discourses became apparent, with the activists asking if their friends who died were not resilient enough? It was felt to fetishise suffering, with women of colour having to consistently be the most resilient, yet rarely benefitting. Linked to this, there was also concern about the plans to ‘build back better’. Given that so many people had lost so much, a common desire was for things to go back to what they were like before, imperfect as they were. Heightening these concerns are the processes of gentrification ravaging the city, a consequence of, as one activist put it, ‘disaster capitalism’.

Anti-resilience poster, New Orleans.

Source: https://twitter.com/sacha_knox/status/921125102087032832

That evening was the weekly meeting of the Justice and Beyond coalition, which brings together a range of community organisations in New Orleans. One of the major concerns was unknown explosions coming from the levees and the canals at night, something which understandably was extremely anxiety-inducing for many residents. But central to the meeting was the sharing of food and discussion before it started, something which not only brought in more people, but also brought them together. As Dr Shaun French notes in his blog social reproduction was a major focus of the AAG conference, and here, yet again, the importance of the unpaid labour, done predominantly by women of colour, was made clear.

The conference

Following on from such a day was always going to be difficult process, but much of the AAG provided quite a stark contrast. The tourist-focused centre of New Orleans further emphasises racial divides within the city and its economy. For a city that is over 60% African-American, so much of the centre is overwhelmingly white. This is of course exacerbated by large of numbers of tourists, but this itself has a knock-on effect. Given the whiteness of so many of these tourists, customer-facing service jobs (which make up a significant part of New Orleans’ economy) are much less likely to be given to people of colour for fear of alienating visitors. People of colour are thus much more likely to work behind the scenes in bars, restaurants, and hotels, emphasising the roles race (and gender) not only play in social reproduction, but in the shaping of economies and cities.

These issues were perhaps most stark on the infamous Bourbon Street, where bars had signs up that supposedly denied entry to people wearing ‘baggy clothes’ and ‘backwards baseball caps’, in a blatant attempt to literally dress up racial profiling. But this was obviously not applied universally (with many white tourists dressed just as described) and instead used to police certain parts of the city. The conference took place in the heart of this New Orleans.

As Dr Cordelia Freeman mentions conferences and political situations can align perfectly, but in the rarefied settings of the Sheraton and the Marriot hotels much of the discussion initially felt very removed from what I had just experienced with the ACORN activists. There is always something incongruous about discussing radical topics at exclusive and expensive international conferences, but given the divided nature of New Orleans these issues felt amplified. However, across the conference real emphasis was placed on important topics such as social reproduction and, in particular, black geographies were foregrounded throughout. (Perhaps I chose wisely/luckily, but I also avoided seeing any all-male panels).

The four-part session my co-presenters and I were part of was titled A Feminist Urban Theory for our Time, and was organised by Linda Peake, Elsa Koleth, Darren Patrick, Rajyashree Reddy, and Susan Ruddick. Across the course of the final day I was able to witness and participate in fantastically interesting, provocative, and, most importantly, supportive set of panels. Research was presented from across the globe, by junior and senior colleagues, and all with a clear focus on how social reproduction shapes cities and urban theory. At the end of the sessions there was even a chance to share stories and strategies about the respective strike actions taking place in UK and Canadian universities.

My time in New Orleans was thus bookended with fantastic experiences, while also reminding me of the many contradictions contained within self-styled radical academia. It has helped me consolidate pre-existing friendships and relationships, and gave me the opportunity to meet a number of fantastic activists, academics, and policy makers. For this my thanks go to the School of Geography for generously supporting me. But most importantly it reiterated to me the importance of socially engaged research, that doesn’t treat ‘the community’ as something separate or homogeneous, but rather an important site of struggle.

[1] ACORN are increasingly active in the UK, doing great work with tenants and communities https://acorntheunion.org.uk/

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply