March 21, 2024, by lzzre

Field Notes From Calais

A blog by Freya Peters, Geography student

My first experience upon arriving in Calais was feeling the bitter wind whip across my face the moment I stepped out of my car. I was there, with the support of the School of Geography Graduate Research Fund, to conduct research with those living in informal refugee camps. On the first morning of volunteering, we were told that the previous night a boat had sunk in the English Channel and five people had died, including a 14-year-old. This was heartbreaking news to start the research with, however, deaths such as this are not uncommon.

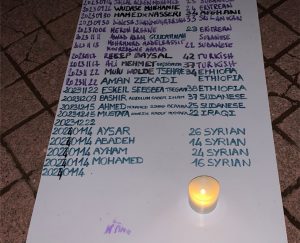

At least 64 people have died in the Channel attempting to reach the shores of the UK since 2018. Later that day, at our distribution in Calais Town Centre, there were three people who had been on the boat that sank, two of them were teenage boys. They were wrapped in foil blankets, still wet, and trying to find somewhere to stay for the night. On such a cold day it was hard to imagine having been in wet clothes for such a long time. I was wearing eight layers and I felt cold having been outside for just a few hours. The following evening, a vigil was organised by an activist group called the Groupe Décès (Death Group) for those who died. At the vigil, the dead were named and added onto a long scroll which listed almost 400 deaths at the border since 1999.

The scroll was placed onto the floor and illuminated by candles, however, it was so long I was unable to read all the names. Attempts by the French police to stop boat crossings often create more danger for refugees because they lead to rushed boardings, or boats being forced to depart from further down the coast where journeys are longer and more dangerous. From a research perspective it is important to consider who is forced to take these dangerous journeys and who is not. When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, forcing Ukrainians to flee for their safety, a number of Ukrainians gathered in Calais aiming to seek refuge in the UK. However, not a single Ukrainian has had to cross the Channel in a small boat, instead, as mentioned during my interviews, the UK government organised for them to travel to the UK on the Eurostar.

Calais represents an intersection of transience and immobility for those waiting to attempt the Channel crossing, either on small boats or by smuggling themselves onto lorries. This journey is exceptionally dangerous but made necessary by the lack of options for safe passage to the UK for a significant quantity of refugees. I performed ethnographic research volunteering with a major humanitarian charity in Calais. The charity distributes non-food items such as sleeping bags, hoodies, underwear and other essentials. It also provides a number of services including hot drinks, a hair cutting station, sewing equipment to repair clothes, English language resources, and a number of games. These attempt to provide some dignity and normality to those living in incredibly challenging circumstances. In addition to the ethnographic research, I also conducted interviews with both staff and volunteers at the charity.

Built on wasteland in and around the city, the camps in Calais are comprised of collections of tents and tarpaulins, often with small fires where discarded wood and plastic is burnt in an attempt to keep warm. Temperatures were below freezing for much of the time I was in Calais and the usually muddy ground was frozen solid. Most of the sites have no drinking water and no waste collection. A number of charities attempt to distribute food and other items to those in tents. The state on the other hand does very little to provide for them. Following a legal challenge, the French state is now obligated to provide food to those within the boundary of Calais. It meets this obligation by outsourcing food provision to the nonprofit organisation La Vie Active, however the food distributions are accompanied by a police escort. Many of the refugees in Calais fear the police and so the fact that food provision comes with a police escort is somewhat problematic. We witnessed this when the police drove past during our distribution at a site where a predominantly Eritrean community lives and many of the men left to return to their camps.

Every 48 hours, the police perform clearings at each of the sites, this is what NGOs in Calais call the ‘zero-anchor point’ approach. They change the timings regularly in an attempt to catch people off guard, often arriving very early in the morning. Clearings usually involve a convoy of police vans arriving at a site and forcibly removing any unattended tents. These tents are not just the only source of shelter for those living outside in the middle of winter, they may also contain personal belongings such as documents, mobile phones, sleeping bags and clothes. Therefore, these clearings significantly increase the risk to migrant lives. In addition, the police have been known to harass, intimidate and assault camp dwellers.

During my research we witnessed a clearing at a site which is comprised of predominantly Sudanese refugees. Performing a clearing during the distribution means that refugees have to choose between risking leaving their tent unattended to collect essential items for survival in the cold weather, including warm clothing and hot drinks, or remain with their tent and miss out on the distribution. Forcing people to choose between such essential items heightens their precarity.

My research draws on theories of necropolitics to discuss this state-sanctioned harm. Necropolitics, as conceptualised by Achille Mbembe involves the sovereign power to sanction death or to keep individuals alive but in a state of injury. The UK government is directly complicit in this border violence because it pays the French state to manage the border and to reduce the number of border crossings. In 2022, for example, the UK committed a further £62.2 million to the French state for border-control. However, these clearings do not appear to deter asylum seekers from attempting to cross the Channel, they merely make life miserable for refugees, forcing them to live in fear and increasingly exposed to the elements in the depths of winter. I intend to situate my findings from Calais in conversation with my longer running research on refugees and asylum seekers living in Nottingham.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply