May 24, 2023, by lzzre

Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site – Milling Power

To mark its 50th anniversary on the 16th November 2022 UNESCO is looking forward to the Next 50!

Imagining a report from the DVMWHS team written in 2072 to celebrate UNESCO 100.

A blog by Ian Jackson

Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site – Milling Power

November 2072 (UNESCO 100 and COP 77)

In hindsight, reviewing the last 100 years of UNESCO (1972-2072), and the Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site (DVMWHS) in particular, it’s hard not to focus on climate change. It’s clear that globally we did too little too late but at least today we have stopped emissions from rising; we, the DVMWHS, can take some pride in the small role we played, leading by example with the Milling Power Project 50 years ago, inspired by those early industrial innovators acknowledged by the 2001 World Heritage inscription.

During the Georgian period (1714 to 1830) in Derbyshire, England, the early industrialists, such as Richard Arkwright and Jedediah Strutt, learnt how to harness the power of the water in ways never imagined before, to drive the world’s first mass-producing textile thread factories, leading to dramatic social and economic changes.

It was impressive to see how these pioneers and communities balanced competing demands on the rivers, such as water abstraction to top-up the new canals, maintaining fisheries (for food and sport) and coping with drought and floods. They developed sustainable enterprises, with some of the DVMWHS sites continuing to harness the power of the river Derwent for over 300 years!

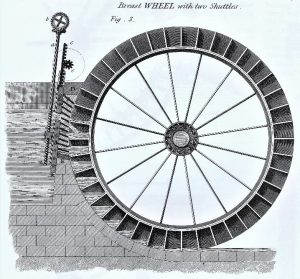

The Hewes Iron Suspension Wheel increased power output five-fold, designed by William Strutt, Belper Mills, Derbyshire Derwent Valley c.1807.

The Cyclopaedia, ed. Abraham Rees, Plates,

vol 4 (1820), “Waterwheels,” pl.2, fig.3

Water remained an important source of power through the 19th century despite the growth of steam, with water-powered sites continuing to harness the free energy as their baseload. During the 20th century waterpower almost disappeared in England, following the government’s creation of a national electricity grid exclusively supplied by large coal fired power stations, and the introduction of charges to Hydroelectric Power (HEP) generators for the ‘borrowed’ water from the rivers.

Waterpower has been a valuable resource globally for thousands of years, but for the last century (1980s-2076) it has been critical in the fight against climate change in its ability to generate HEP. Hydroelectricity can be a divisive and controversial technology, especially large HEP schemes: one such development, Lake Nasser in Egypt, created for water storage and HEP generation, led to the international call to save key monuments and, ultimately, the formation of UNESCO 100 years ago in 1972.

In the DVMWHS, HEP at Masson, Belper and Milford Mills had been refurbished in the 1990s by Derwent Hydro Power, but Cromford Mill museum’s HEP installation in 2023 (using the 1776 wheel pit), the discovery of Strutt’s historic mill fishways and the Derwent Valley’s Waterpower museum and academy in 2024, all helped catch the imagination of local communities.

Learning the lessons from the past, the DVMWHS proved that balancing river ecology and HEP was achievable. The Derbyshire Derwent Catchment (DDC) ‘Milling Power Project’ started in 2025, as part of the newly formed East Midlands devolved administration’s Climate Action Plan, and in just 6 years achieved the project’s goal of 100 low-carbon HEP stations operating in the DDC. By 2031 (the DVMWHS’s 30th anniversary) Derbyshire had become a centre of sustainability excellence, with the DVMWHS at its heart.

While the DVMWHS assets suffered from the consequences of not dealing with climate change soon enough, the ‘Milling Power Project’ breathed new life into over 100 sites reinstating their HEP generation, improving the waterways and the resilience of their buildings. Supported by local authorities and community energy initiatives, homes, holiday lets and small businesses on historic watermill sites became beacons of good practice. Addressing sustainability and resilience gave the DVMWHS a new focus and purpose, protecting sites and promoting achievable climate change mitigation and adaption solutions.

Following the project’s success, similar catchments around the UK followed suit and by 2050, most former watermill sites with weirs in place, had regenerated their waterpower and waterways. By 2050, across Europe many of the 65,000 historic watermills identified in the Natura 2000 micro-hydro project were again producing waterpower.

It’s hard to identify what exactly initiated the DDC ‘Milling Power Project’, but a combination of global, national and local events meant the DVMWHS historic watermills’ sustainability became an opportunity, rather than a problem, and led to the changes we can still be proud of today, nearly 50 years later.

Certainly, the extreme weather during the 2020s led to a major rethink of many existing policies and regulations, looking through the prism of climate change. Impacts on seas and waterways, such as drying rivers, changing fish migration patterns and invasive species across Europe led to a significantly revised Water Framework Directive, including local river catchment-based regulation to identify and deliver improvements. One important change allowed the DDC partnership rivers’ experts to accommodate fish passage alongside HEP, rather than a national ‘fish pass expert panel’ creating obstacles to HEP and fish passage projects.

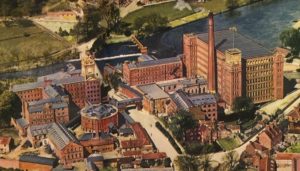

The Belper Mill complex, 1921. Generating its own power, with 10 small HEP turbines plus 2 steam turbines.

Aerofilms, Aerial View of the Belper Mill Complex

(1921, colourised 1947 by English Sewing Cotton Company, restored by Adrian Farmer), from the collection of the Belper Historical Society.

Droughts through the 2020s disrupted electricity supplies across Europe. It wasn’t only Norwegian HEP that was affected, German coal fired power stations and French nuclear power stations were impacted with coal barges stranded and cooling water restricted. (How Europe’s drought is making Britain’s energy crisis worse (theconversation.com)).

The 2022-24 energy crisis that followed COVID 19 and the attempted occupation of Ukraine, primarily linked to gas, was a global shock similar in extent to the 1970s oil crisis which led to the scaling up of nuclear power. But after some early desperate attempts to source alternative fossil fuels, the realisation that home grown renewables provided secure, affordable and sustainable energy, led to changes that allowed local renewable energy to be developed by local communities. (After Ukraine – The Great Clean Energy Acceleration | BloombergNEF (bnef.com))

The UK government restructured markets and regulations in the energy sector to enable capital investment around assets and projects that delivered societal value, including the mitigation of climate change. Legislation was introduced requiring statutory consultees and planning authorities to prioritise Climate Change mitigation in their planning decision making. The ‘Milling Power Project’ was also helped by regulatory changes that redirected fossil fuel subsidies to support HEP with integrated fish passage and the Local Electricity Act (2023) that allowed local HEP generators to supply clean electricity to their communities.

2007 Torrs Hydro, New Mills Derbyshire. The first community owned HEP site in the UK with fish friendly archimedes and integrated fish ladder. Photographs by Ian Jackson

Today (2072) we take so many things for granted that we had forgotten we knew how to do 50 years ago: in addition to seeing our milling power returned, we have tidal power (as per historic tide mills) providing a reliable baseload of energy around the UK and water reservoirs now having multiple functions, including Pumped HEP for energy storage and on demand electricity generation (as per historic mill ponds and dams).

Learning from the 18th century entrepreneurs, innovators, and communities of the DVMWHS, the Derbyshire Derwent Valley re-learnt how to use its natural resources effectively, balancing the HEP, drinking water and fish demands of our rivers, using its platform as a World Heritage Site to share sustainability best practice, acting locally to make a difference globally.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply