December 4, 2018, by lzzeb

Repton Revealed

A blog by Professor Emeritus of Cultural Geography, Stephen Daniels

The exhibition Repton Revealed, which I have curated at the Garden Museum, Lambeth, celebrates the bicentenary of the landscape gardener Humphry Repton, and runs till February 2019.

https://gardenmuseum.org.uk/exhibitions/repton-revealed/

It brings together many key works on paper of his career, including 24 of his hallmark Red Books of designs, with their alluring watercolour designs, as well as exhibition drawings and published volumes. For me it has been a revelation to revisit Repton and his work, on which I wrote a monograph in 1999 (Yale University Press), and the research has turned up new discoveries as well as opened fresh perspectives.

One of the challenges of the exhibition has been to display the works in a way which reveals the repertoire of Repton’s landscape imagery, from prospects and vignettes to maps and plans, in precious works which are relatively small and fragile, and originally made for leafing through by hand. So a fair proportion of the budget was spent on exhibition design, based on a Repton interior, with customised display cases and a digital animation of one Red Book. This was of an industrial landscape, near Leeds (and the work which initially prompted my pursuit of Repton as a post graduate). The animation not only showed the transformations from one view to another, but the process of painting the watercolours, and images which were originally expressed in words in the text, not illustrated. And with a voice over by actor Jeremy Irons as Humphry Repton.

The ‘reveal’ theme for the exhibition is intended to show how Repton’s art was affiliated with forms of popular show and spectacle, including miniature theatres, magic lanterns, scenic pantomimes, panoramas, and peep shows. Peep shows, or raree shows, as they were known in Repton’s time, were not the dodgy ‘what the butler saw’ entertainments they later became, but a form of geographical entertainment and instruction, portable theatres set up the street by travelling showmen, which showed a succession of wonders of the world when spectators peered into the peep hole as the showman told traveller’s tales of the scenes on show. Not only were Repton’s Red Books likened to raree shows, but ‘The Peep’ was a form of view that Repton created in the places he was commissioned, cutting away a circular aperture in shrubs and trees to reveal a wonderful landscape.

The exhibition is part of a range of events this year – excursions, conferences, picnics, school projects — many put on by local and regional organizations. The Big Red Book project sees The Gardens Trust and Warley Woods Community Trust work with a West Midlands school to learn about their landscape and history through Repton’s design for Warley (now a public park, and unusually the original Red Book is kept by the local public library).

http://www.abbeyfederation.co.uk/year-6/

Like a travelling showman I have been touring the country, giving shows on that modern magic lantern, the digital projector, presenting Repton’s work with particular attention to the places I visit. The venues reflect Repton’s own social range of clientele: mansions, villas, museums, churches and village halls (in one village my lecture was billed alongside line dancing and bag making). These local organizations have been highly productive, and creative, in researching Repton’s work, including publishing a number of fine volumes revealing the findings of new research, newly discovered designs and a great deal of archival and field work, placing Repton in a longer history of landscape change. It is a groundswell of grass roots knowledge, to which I have been indebted in curating the exhibition. And there are wider implications here about the models of public engagement and impact academic researchers deploy, particularly in the light of geography’s current regard for amateur or lay expertise and enthusiasm.

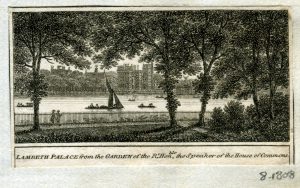

It was archival work by a researcher for the Sussex Gardens Trust which helped me recently reveal a new Repton commission within sight of the Garden Museum. In my touring lectures I showed a Repton drawing for a pocket diary, of a Thameside garden at Westminster, that I had a strong hunch was a design of his, but no direct evidence. At a lecture in Kent, a member of the audience intervened to say he was sure he had proof. And so it proved. Letters from Repton to Charles Abbot, a client in Sussex revealed that he also worked for Abbot in his role as Speaker of the House of Commons. He laid out the Speaker’s pleasure ground at the Palace of Westminster, with a view of the church, St Mary’s Lambeth, which is now the Garden Museum, as part of the reconstruction of Westminster after the political Union with Ireland. This discovery has not just added another commission to the list, but has transformed my view of Repton’s work as a whole, and set in train a further project on his work as an urban planner, as part of reshaping the landscape of the British state: Repton Revisioned.

So much on Repton this year but this was really enjoyable — a five star exhibition