August 28, 2018, by lzzeb

The real rumble in the jungle: violence, conflict, gold mining and environmental destruction in the rainforests of Colombia

A blog by Dr Nick Mount

Colombia is in the process of transitioning from one of the most protracted civil conflicts in the world to peace. However, one of the major questions for post-conflict transition in Colombia is how to ensure the inclusion and participation of vulnerable and marginalised groups in transition processes so that their knowledges, abilities and capacities are represented, and so that they can influence post-conflict development. This question is particularly challenging in regions of the country where the conflict is fuelled by illegal alluvial gold mining that destroys the fragile riverine environment and degrades the culture and communities of the people that live in it. In Choco, a global biodiversity hotspot on the Pacific west of Colombia, the situation is so bad that as much as 65% of some river catchments have been affected. With no effective state-led security, the environmental destruction is able to continue unchecked, local communities are forcibly displaced and there is no requirement for any rehabilitation of the rainforest once gold extraction has finished. These communities who are the legal owners of the land, and have been awarded constitutional court recognition as the legal guardians of the river, are powerless to intervene and protect their own livelihoods and the environment that support them.

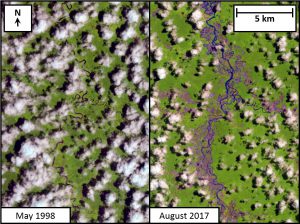

Destruction of the Rio Quito river basin observed from the Landsat TM (left) and Sentinel 2 (right) satellites. The Rio Quito has seen upwards of 6% of its riverine environment destroyed by alluvial mining in a little over a decade.

My study leave in 2018 found me on travelling the jungles of the Choco region to experience the environmental destruction first-hand, and to meet the communities affected by it. I had been invited to become part of a multi-disciplinary team of UK and Colombian researchers that will work alongside and advocate for Choco communities, as well as discover fundamental new insights into the complex inter-relationships between conflict, violence, communities and the environment. My expertise in river science were augmented by those of political, social and environmental scientists from Glasgow and Portsmouth Universities, the Technical University of Choco and NGOs including the Scottish Catholic International Aid Fund and AB Colombia.

What we know from conflicts including Northern Ireland and South Africa is that innovative community engaged and participatory processes can achieve greater inclusivity in peace building processes. We also know that inclusivity of all actors is key to fully understanding the complexities and nuances of conflict and its socio-environmental that are critical for building a sustainable peace process. However, a key question remains: how might different conflict actors can be encouraged and facilitated to articulate their knowledge and experience of conflict in ways that enable their actions to be explained to one another, and that support a shift from narrow understandings of the causes of conflict based on personal experience to more expansive understandings that are based on collective experiences? This is an especially difficult question to answer if (as is the case in Choco) one of the most important actors is a river rather than a person!

The turbid waters of the Rio Quito (right) entering the Atrato River (left). The sediment released by illegal mining destroys fish habitat and alters the configuration of the river bed to such an extent that the river is unlikely to recover via natural means.

Answering this question is the focus of the recently-funded ESRC ‘River Stories’ project that emerged from our Colombia visit and was the major output of my study leave. In this project, we will be focussing on riverine communities along the Atrato River – the main artery of Chocó. Atrato communities have been deeply impacted by armed actors who are engaged in widespread alluvial gold mining which is a key factor in their forced displacement and the loss of traditional, sustainable livelihoods. Despite a 2017 Colombian Constitutional Court ruling to empower Atrato communities with ‘bio-cultural rights’ that protect their land title and livelihoods, they remain marginalised. They struggle to make their voices heard and to influence and inform peace building processes. This marginalisation has also been experienced by the river itself, whose voice has been silenced through the abandonment of state-sponsored environmental monitoring programmes at the height of the conflict. As a result, the effects of conflict and alluvial mining on the form and function of the river, and the impacts of these on interactions between armed actors, the river, and the communities it sustains are poorly understood. This will only be addressed if marginalised voices of communities and the river are articulated and amplified so that their knowledges, abilities and capacities can be integrated into sustainable peace building processes.

The River Stories Project is a collaboration between the Universities of Glasgow, Nottingham and Portsmouth, the Technical University of Choco and NGOs including WWF, the Scottish Catholic International Aid Fund, AB Colombia and Tierra Digna.

Conceptually, the project will build on a key emphasis of peace processes worldwide: the capture and re-telling of testimony so that conflict actors can better appreciate the complexities of the conflict in which they are engaged, and the interrelationships and feedbacks between their actions, and those of others, which fuel the conflict. Such knowledge is a fundamental precursor to the development of sustainable and feasible strategies for peace. The project is structured and designed to elicit, analyse and co-produce testimonies as an integrated ‘river story’, sourced from multiple participants and perspectives – including marginalised human actors and the river itself. It therefore uses an innovative and multidisciplinary methodology that brings social scientists and natural scientists together – integrating their research methods and techniques to capture human stories through community-level, participatory research and the river’s story through field-based scientific monitoring and environmental reconstruction and mapping. The story books that we will produce, and the policy briefs that they will underpin, will be the vehicles through which policy-makers are bought into dialogue with the marginalised voices of both riverine communities and the river itself, and thorough which they improved understandings of the key actors and drivers of conflict in Chocó and the priorities and strategies for sustainable peace building, will be gained.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply