March 19, 2019, by Richard Bates

Writing About Florence Nightingale: Annie Matheson’s 1913 Biography

Our second guest blog comes from Val Wood, a former nurse and nurse educator and supporter of a number of historical and heritage initiatives across Nottinghamshire. Val is chair of Nottingham Women’s History Group.

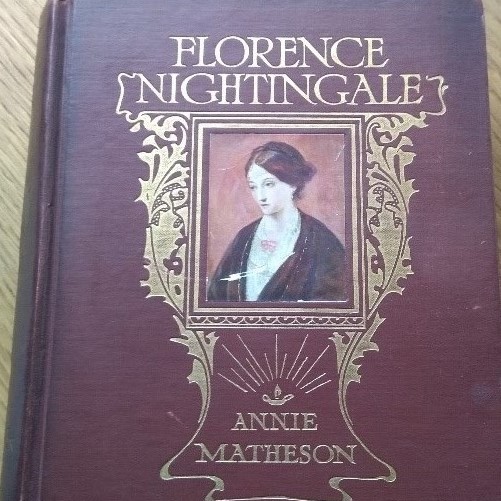

Right: Cover of Matheson’s book, published 1913 by Thomas Nelson & Sons, London. Image courtesy of Rowena Edlin-White.

Over fifty biographies have been written about Florence Nightingale since her death in 1910, and at least one (The Life of Florence Nightingale by Sarah Tooley, published in 1905) appeared before this date. The first authorised biography, Sir Edward Cook’s two-volume account, was commissioned by the executors of Nightingale’s estate in 1913. According to later biographers, Cook’s remains the ‘unsurpassed account of the attempt to overturn the sentimental legend’ (Bostridge, 2008: 528). That legend emerged in the wake of the Crimean War, in newspapers and in the extensive eight-volume account of the war written by A.W. Kinglake (1863-1887) (see the recent blog post on this topic by Jonathan Memel, from the project team).

Another early biographer of Florence Nightingale was Annie Matheson (1853-1924), a poet, essayist and feminist who lived in Nottingham, later relocating to London. A prolific published writer from 1890, she wrote several books of poetry and verse, songs and hymns, biographies and stories for children. Florence Nightingale: A Biography was published in 1913, and aimed at younger readers than Cook’s biography of the same year – Matheson included a note in the introductory chapter for ‘The Elders in my Audience’, which suggests that the biography would also have interest to ‘people of my generation’. Matheson acknowledged that the writing of this biography had caused her some anxiety, as she had not been aware that Cook’s officially authorised life was about to appear. But she went on to note ‘he put no obstacle in my path’. She also acknowledged the ‘large hearted generosity’ of Sarah Tooley, and the permission granted by the suffragette Marion Holmes to quote from her inspiring monograph on Nightingale published in 1913 by the Women’s Freedom League.

Matheson’s 1913 biography of Nightingale is a celebratory text, and the prose is often gloriously overblown in its praise of its subject and her accomplishments. According to Matheson, Nightingale was ‘swift, efficient, capable to the last degree and she was also high spirited and sometimes sharp tongued’ (p. 231). She was also, ‘a wise virgin whose lamp had been trimmed and daily refilled with ever finer quality of flame’ (p. 142). However if the writing style is set aside, the biography can be described as a comprehensive and well-researched account. Matheson did not have the access to Nightingale’s archive that Cook enjoyed, but nonetheless drew upon substantial primary research material in the form of letters written by Nightingale and others.

The 1913 publication date is significant not just for its proximity to Nightingale’s death but for the context of the women’s suffrage movement, which was reaching a peak at the time. The Edwardian women’s suffrage campaign, casting around for iconic women to illustrate its push for the vote and women’s emancipation, utilised imagery of notable women. The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, for example, deployed a banner emblazoned with ‘FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE’ and ‘CRIMEA’ in large capitals, which was specially designed by Mary Lowndes for the 1908 Pageant of Great Women.

Annie Matheson. Image courtesy of Rowena Edlin-White.

In her biography of Nightingale, Matheson relates that ‘Britain was very proud of the daughter who had become so mighty a power for the good of the state’, and Nightingale was the ‘the highest embodiment of womanhood and of citizenship’ (p. 292). Matheson was sympathetic to the suffragist cause. Her 1900 poem ‘A Song for Women’, about sweated labour in the garment industry, was taken up as an anthem by the Women’s Trade Union League (Edlin–White, 2015:9). In her biography, Matheson was keen to claim Nightingale, alongside prison reformer Elizabeth Fry, as a supporter of household suffrage for women (p. 344). Matheson and Marion Holmes both wrote biographical accounts about Fry as well as Nightingale – Matheson’s was published in 1920 under the title of A Plain Friend.

Matheson’s publication of a biography of Nightingale also marked a change in the access of primary research material available to prospective biographers. Three years after the death of Nightingale in 1910 the executors of her will and her family were becoming aware of the value to others of her writing, letters and diaries. They felt a need to exercise constraint over its use and were guarded both against the potential for misinterpretation and overly-sentimental eulogising of her achievements. This caution was to some extent borne out by Lytton Strachey’s 1918 essay on Nightingale in his book Eminent Victorians, which sought to explode popular myths about her and draw attention to the contradictions in her personality and beliefs, in the context of a wider post-WWI irreverent dismantling of Victorian values. There followed a decline in the works of popular biography about Nightingale, particularly those addressed to young girls.

However, in the 1920s the posthumous publication of Nightingale’s novella Cassandra, about the lives of women in mid-nineteenth century Britain was taken up by younger feminists who had achieved voting parity. When Ray Strachey (1887-1940) related by marriage to Lytton Strachey, published her short history of the women’s movement in 1928, she included Cassandra as an appendix and the work became an important feminist text.

Matheson continued writing until her death in 1924. Her ashes were interred in Nottingham General Cemetery, in the grave of her parents.

Val Wood

A booklet researched and published by Rowena Edlin-White on Annie Matheson’s life is available from the author: please contact ro@edlin-white.net.

Further Reading

Mark Bostridge, (2008) Florence Nightingale: The Woman and her Legend, Penguin, London.

Hi to all, the contents existing at this web page are really remarkable for people knowledge,

well, keep up the nice work fellows.

Hi to every body, it’s my first pay a visit of this

web site; this webpage includes amazing and in fact good material

designed for visitors.

Pretty section of content. I just stumbled upon your website and in accession capital to assert

that I acquire in fact enjoyed account your blog posts.

Anyway I’ll be subscribing to your augment and even I achievement you access consistently fast.

Highly descriptive article, I liked that a lot. Will there be a part 2?