September 18, 2014, by Tom Stafford

The minimal cognitive commitment model of implicit bias

Previously, we have discussed (one, two) the multiple meanings of implicit in implicit biases. Implicit is often intepreted as implying ‘unconscious’ in some strong sense (in the popular press), or as implying a lack of awareness and control (in the scholarly literature). Even in the scholarly literature it is rarely systemmatically defined exacly what kind of awareness we are discussing.

Because of this, when I read the word ‘implicit’, I don’t intepret it as meaning ‘unconscious’. Instead I think of it as merely meaning ‘revealed by measuring behaviour rather than declaration’. Let’s call this the minimal cognitive commitment model.

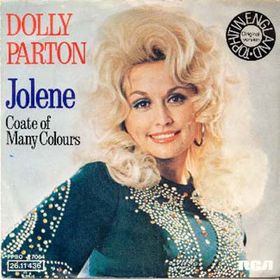

Here’s the example I’ve been using to train my intuitions when thinking about implicit biases. Suppose you ask me in public “what’s your favourite piece of music?”. I will answer with something based partly based on my preferences/beliefs, but also, to some degree influenced, by self-presentational worries, what I think you want to hear, what I think the right answer is and so on. Probably I answer with something revealling my taste and sophistication, choosing something avant garde, or obscure. Now, supposed you try to find out the answer to this question yourself by looking at my computer and sorting the tracks in my my music software by how often they’ve been played. Surprise! What comes out top is not something classical-yet-contempory by Philip Glass, nor the unrealeased b-sides from early 90s New York jazz-hipsters, but instead, probably, something more accessible. Maybe it is Jolene by Dolly Parton. So it turns out I have an implicit preference for for Jolene.

Does this mean I didn’t know about my love for Jolene? That I couldn’t have reported, or wouldn’t have reported it, if you’d have asked me in the right way? Does it even mean that I wasn’t telling the honest truth when I answered your question earlier? No, none of these. I might know that I loved Jolene, that I listening to the track more than any other piece of music. I may also have considered it as answer before interpreting the question in a way that meant it wasn’t the correct answer (so, for example, maybe ‘favourite piece of music’ means ‘piece which has been most influential on me’ or ‘piece I believe I’ll still enjoy in ten years’ time’).

The example is silly, but the moral is not: implicit measures in psychology do not – on their own – imply any strong commitments with regard to awareness.

Your view seems to be very much in line with what Fazio and Olson (2003, ‘Implicit Measures in Social Cognition Research: Their Meaning and Use’) say about ‘the implicit’. They notice that implicit measurement procedures can’t guarantee that participants are unaware of their attitudes and that a mismatch between scores on implicit and explicit measures doesn’t warrant this assumption either. They suggest that it is the measure that is explicit or implicit and not the attitude. Explicit measures rely on self-report and implicit measures not. In a footnote, they admit that they prefer the terms ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ measures, because this circumvents the confusion produced by the connotations linked to the words ‘implicit’ and ‘explicit’. However, they stay with the latter terms as they “appear to be firmly entrenched in the literature”.

I agree that it would be good to speak of ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ when it comes to measurements. However, I am not so sure whether we should dismiss the talk of implicit attitudes altogether. After all, there might indeed be attitudes that people are not aware of. For example, some participants might genuinely be surprised about their IAT score, and I might even learn something new about my music taste after analyzing my music hearing habits (I might learn that I have a preference for a certain class of melodies). Those attitudes that we are not aware of (implicit attitudes in the narrow sense) are captured by indirect measures, but these measures might capture attitudes to which we have access as well.

Any thoughts on this?

I find myself agreeing with both of you here. Tom is correct to say that we should not assume people lack awareness of things recorded using implicit measures. But I also think Andreas is right that we should not completely abandon talk of implicit attitudes. It seems obvious to me that individuals will have some preferences they are unaware of. We might lack awareness of certain patterns in our behaviour such as Andreas’ example of discovering a preference for a certain class of melodies. There will also be case where we lack awareness of the influence of a preference regardless of whether we are aware of the preference in the first place. Such as not realising our rejection of a particular job candidate is predominantly based on their gender. The big difficulty is gathering evidence of such cases. It is not clear that we currently have any measure which is exclusively sensitive to cases where individuals lack awareness.

Tom’s minimal cognitive commitment model stops us drawing unwarranted conclusions about the nature of implicit biases but it also leave the concept ‘implicit’ low on explanatory power. That is to say, it does not help explain what features implicit things have. Nor does it properly explain why there is often a difference between results acquired using implicit and explicit measures. It seems like a starting point from which one needs to think about the common features of implicit measures and generate a definition/concept with greater explanatory power. Might there be some features common to preferences recorded using implicit measures? Or might there be some features common to cases where implicit and explicit measures come apart?

I think there is some promise in the later. Any thoughts?

I tend to think of a continuum between the two types of preferences that have usually been described as ‘implicit’ and ‘explicit’. According to this, there would for instance be various degrees of awareness (in its many senses) possible between these two extremes (other features that are thought to be characteristic of the implicit-explicit distinction can surely be added). To me it seems that self-report measures capture preferences at one very end of this continuum: Those preferences that are high in awareness (again, add whatever feature you think is characteristic). Indirect measures like the IAT, while leaning towards the other end, seem to capture a much wider range of the continuum.

However, I am not sure whether there might be features of the implicit-explicit distinction for which no such continuum is plausible. Is it for example plausible to assume that there are various degrees of vulnerability to self-presentational bias or might this be an all or nothing affair? What about automaticity? Finding features that are either present or not present in those preferences measured by indirect and direct measures might help us to develop a more clear-cut distinction between the implicit and the explicit.

It might be useful to distinguish between things of which one is not aware and things it is not possible to have awareness of: Tom’s post helpfully points out that the discussions about implicit bias rely on the idea that it is not possible to have awareness, but that this is mistaken. However, that is perfectly consistent with the claim that sometimes (for various reasons, self-presentation etc) individuals may not in fact have awareness of the bias (though they could). But that is a feature shared with many cognitions typically thought of as explicit – there are certain beliefs, with propositional contents, of which I don’t at any one time have awareness.

So the *aware/unaware* criteria seems a poor distinguishing characteristic to me. And the *could/could not be aware* criteria doesn’t seem adequate either, for the reasons Tom mentions.

This is not to say (agreeing with Andreas) that we should ditch the term ‘implicit’, but that it shouldn’t be supposed to track either of these distinguishing criteria.

Robin’s method of considering what has explanatory power seems very useful: does the notion posited do any explanatory work (we might also ask what normative work it can do – that might be a reason for preserving the notion, even if it does not have great explanatory power)?