January 22, 2014, by Jules Holroyd

Introducing the Project Blog

Welcome to the blog that charts the progress of our three year Leverhulme Trust funded research project, on Bias and Blame.

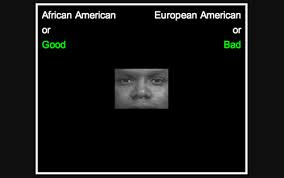

Suppose it turns out that our behaviour is influenced in subtle ways such that we often unintentionally treat people differentially, or unfairly. Many studies in psychology have found this to be the case: for example, the CVs of men and women are evaluated differently (Valian, 1999); CVs with white-sounding and black-sounding names are evaluated differently (Dovidio & Gaertner, 2000); in pictures showing a person holding an ambiguous object, that object is more likely to be judged to be a weapon when the person depicted is black (Payne 2006). These effects are often found even in fair-minded, anti-racist and anti-sexist individuals. Such behavioural effects are attributed to ‘implicit biases’ or ‘implicit associations’: fast, automatic connections that operate beyond the reach of direct or reflective control. You can take an online Implicit Association Test, (from which the above screen shot is taken) to see whether you express any implicit biases.

This is worrying. So how could we change our judgements and behaviours so that these kinds of ‘implicit biases’ have less influence, or are eliminated? One strategy is to remove the information that permits biases to operate: anonymise CVs, for example. But this is not always possible. Psychologists have studies other ways of limiting the expression of implicit biases, or trying to change them. (We’ll talk about some of these in more detail in later posts).

What we are investigating is whether moral interactions have a role to play in mitigating the influence of these biases. Whether or not individuals are or are not responsible for expressing implicit biases, there is a further question about whether blaming each other for them helps or hinders us in limiting the expression of them. If it turns out blaming does help each other to limit the expression of implicit biases, then there is a reason counting in favour of blaming each other. (Before knowing whether to blame, we would also have to consider other reasons, such as whether people in fact are blameworthy for manifesting these biases; and how easy or costly it is to blame people in these ways. We hope to address this in the theoretical part of our project also).

As far as we know, no one has asked or answered this question. We’re aiming to bring together methods from empirical psychology and analytic philosophy to address it. We hope that our research will yield important and interesting findings that help us to understand how we should interact as moral agents who are also biased beings. And we hope to benefit from useful discussion, on this blog, of the research questions we encounter along the way!

Jules Holroyd – Principle Investigator, Department of Philosophy, University of Nottingham

Tom Stafford – Co-investigator, Department of Psychology, University of Sheffield

Robin Scaife – Post-doc, Department of Psychology, University of Sheffield

And you? We’re seeking a PhD student – Department of Philosophy, University of Nottingham

In my opinion, the common interpretation people have of the study of black-sounding vs. white-sounding names is very silly. Anyone who has spent time among African-Americans knows that “black-sounding names” are valid class indicators. Middle class blacks do not name their kids black-sounding names nearly as often as urban underclass black people do. I would be amazed if black-sounding names are not quite strongly associated with criminal behavior and poor school performance (maybe some sociologists have checked). There is a white equivalent: southern “cracker names” like Billy-Bob.

Would it show anti-white prejudice that people tend to negatively evaluate people named Billy-Bob (as I bet they would, as you probably would too)? No, it would show that they are able to pick up on the statistics of their world. Is employing those statistics in a Bayesian-reasonable way an “implicit bias”? Well not if by “bias” you mean something that results in a less accurate inference, on expectation. (A similar point can be made about the gun study. Racial disparities in violent behavior are shown by all stats, and you don’t even have to believe the police–you can look at the crime victims’ report stats and find the same thing.)

And who says any of this is “implicit”? If you asked people to explain themselves at length, and inclined them to speak openly, I bet a lot of them could probably come pretty close to what I just said above. So your project goal is to cure people of statistical rationality or to make them less candid?

@Maggie

You raise a good point about the potential confound. Other versions of the IAT use faces, which aren’t obvious class indicators, and get similar results. See http://www.understandingprejudice.org/iat/faqrace.htm

On the “bayesian” intepretation of implicit biases, I recommend these two papers

Arkes, H. R., & Tetlock, P. E. (2004). Attributions of implicit prejudice, or “would Jesse Jackson ‘fail’ the implicit association test?”. Psychological Inquiry, 15(4), 257-278.

http://www.stthomasu.ca/~nhiggins/Arkes_Tetlock-2004.pdf

Gendler, T. S. (2011). On the epistemic costs of implicit bias. Philosophical Studies, 156(1), 33-63.

http://philosophy.rutgers.edu/dmdocuments/Gendler%20%282011%29%20On%20the%20Epistemic%20Costs%20of%20Implicit%20Bias%20May%202011%20Phil%20Studies.pdf

And on the issue of what “implicit” means, I recommend Robin’s recent post on the project blog:

https://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/biasandblame/2014/02/24/what-is-implicit-about-implicit-biases/

Even in the strong case in which a rational, fully explicit, account of implicit bias is upheld it will still be of interest to see how moral interactions interact with these associations (e.g. in cases where you wish to disavow associations which contradict your other beliefs, or when you might wish to design situations where having a name associated with being poor and black doesn’t generate unnecessary disadvantages).

Thanks Tom, for those references.

The point about class bias is an interesting one. I don’t know of studies that have looked specifically at class biases. It wouldn’t be surprising, I guess, to find similarly worrying biases in relation to class identity. As Tom says: if the aim is to eliminate problematic biases that distort judgement in undesirable ways (surely judging differently otherwise identical CVs is a case of this!), then finding out strategies for doing so seems worthwhile. We’re just looking at some associations – addressing everything in one study is not possible!

[…] this lab measure with the reality of implicit bias ‘in the wild’. In particular, along with some colleagues, I have been interested in exactly what an implicit bias, is, […]