April 25, 2014, by Stephen Mumford

Books for Prisoners

In 1981 I saw the TV premier of A Sense of Freedom, a film about violent convict Jimmy Boyle. Serving a life sentence for murder, the Glasgow gangster faced down one attempt after another by the prison authorities to crush his spirit. Perhaps they thought they could beat the bad out of him. But it didn’t work. The effect of brutality was to make Boyle even more brutal in return. He looked like a hopeless case: irredeemable, serving his time but surely not fit to be let back on the streets.

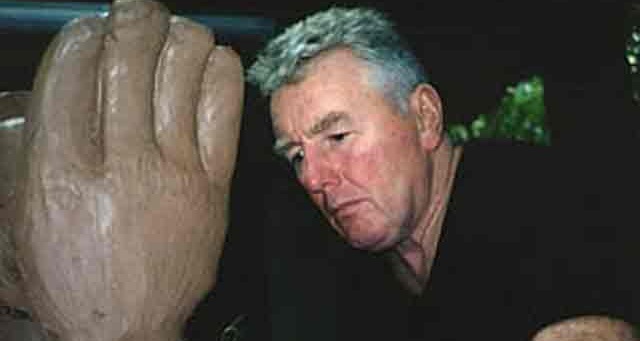

Somebody somewhere had the idea to move Jimmy to a special unit in which he was trusted, respected, allowed to develop his interest in sculpture and basically be treated like a human being. On arrival at the unit, he was lost for words when a guard handed him a knife so that he could cut open his small parcel of belongings. A passion for the arts was allowed to grow. Boyle started to write: first an autobiography and, since, a play and a novel. And his sculptured output was well regarded too, deserving public exhibition. Boyle was in due course released, did not re-offend and has remained a consistent contributor to the art world. Boyle did many bad things but he has done many other things since that deserve praise. More than that, the direction of his life was turned around. He could have made no useful contribution to society. But now he has.

The film made a big impression on me. I was 15 when I watched it but have not forgotten. Perhaps not every prisoner who is treated in this manner responds so well. One did. Art, culture, expression, gave Boyle a voice: a vehicle whereby his frustrations could be directed in other ways.

And now I hear that books are banned in UK prisons, for fear their receipt might aid inward smuggling. This seems very sad. Many things create the possibility of abuse and law breaking – a car can be used to speed or to get away from the scene of a crime – but we don’t think the possibility alone justifies a ban, from which all suffer. A book can be the only lawful liberation and escape when one is confined. And the world it opens up might – who knows – be exactly that which sets a repeat offender on the road to reform.

We are all prisoners of our circumstances, captured and constrained by our culture, time and economic situation. Books transport us to other worlds, historical epochs and different lives. They allow us to dream about what else is possible. And they often put us in someone else’s shoes, giving an insight into new perspectives. To ban books from someone is to dehumanise them. It says that the world has given up on them. Then is it any wonder if they give up on themselves?

Lovely post. One point of information, though: the books have not been banned as a security risk. The Incentives and Earned Privileges scheme document clearly places books in the ‘privileges’ column, not the separate ‘security risk’ column. When Chris Grayling said that books were a security risk he was either being disingenuous or ignorant of his own department’s policy.