April 13, 2014, by Stephen Mumford

Being Sensible

Some recent Arts Matters posts might have perpetuated the myth of the five bodily senses. Of course there are many more even if we restrict ourselves to human beings. And if we include animals, we find others besides. Bats make their way around using echolocation, as every philosopher knows because of Thomas Nagel’s paper ‘What is it like to be a bat?’. Echolocation provides an accurate 3-D ‘view’ of the world, while we humans just have to judge it from sight, having two eyes a slight distance apart. With loss of an eye, we struggle. While I have exalted readers to enjoy their senses, I have always been aware of the possibility of sensory disability. Not everyone has each of the traditional five senses. Yet we can all think of ourselves as disabled relative to the bat. It has a sense we don’t. Disability is a relative notion.

Even Wikipedia knows there are more than five human senses. We have thermoception feeling changes in temperature and nociception sensing pain. There is a sense of balance and acceleration and a sense for oxygen levels that can produce a feeling of suffocation. The bladder contains sense receptors that tell us it’s time to visit the bathroom.

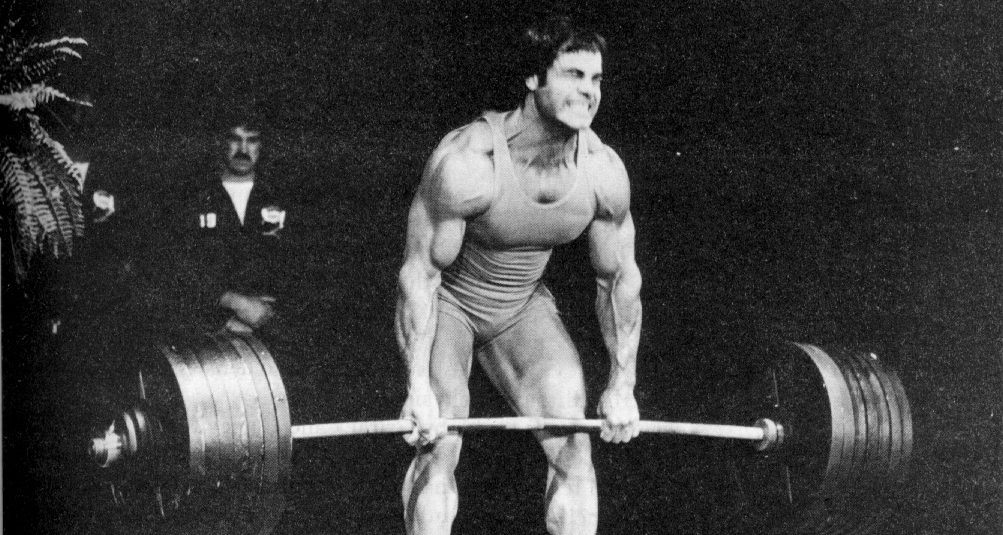

But the most important ‘sixth sense’, for which there ought really to be no excuse for its neglect, is proprioception. This is the sense of kinaesthetic experience, of movement and coordination, and of required effort in our actions. The feeling of muscular strain tells us when we need to try harder to lift a heavy object or occasionally that we have tried too hard when the object is light. Have you ever gone to lift a suitcase in the belief that it is fully laden, for instance, and then had a surprising corrective sensation? Proprioception gives that sense of necessary effort, providing feedback on our bodily movements.

For philosophers who work on causation, proprioception has a vital place. It is through this sense that we know we are causally engaged with the world. We feel pushes and pulls when causes act upon us. And when we act to initiate change, we feel the world resist us. Often we have sufficient power to overcome that resistance and succeed in our intentions. While we can see, hear and sometimes taste the difference our actions make on the world, proprioception gives us the most immediate and direct experience of what it is to be causally connected to the world. By limiting our investigations to the traditional five senses, we might miss this vital metaphysical insight.

David Hume’s account of causation from Treatise of Human Nature (1739) still dominates in philosophy. He claimed he had no direct experience of causation, yet he restricted his examples mainly to the visual experience of a succession of events. To that extent, in his thought experiments he effectively disabled himself, imagining he lacked that very sense that allows him to experience causes. He even confessed in the Conclusion to Book I that when he wasn’t doing philosophy he believed in causes the same as everyone else. What he didn’t see, sadly, was that there was an assumption in his arguments about the nature of his experience that explains why his philosophy and common sense were at odds. I say this is sad because Hume’s thinking on the topic still persists and pervades many suppositions of analytic philosophy, throughout metaphysics, logic and philosophy of science.

For further discussion of proprioception in relation to knowledge of causal engagement with the world, see our recent book Getting Causes from Powers (with Rani Lill Anjum, Oxford 2011).

You’re channeling Reid! I love it! Right down to “common sense.” Essays on the Active Powers of Man is wonderful. Even if he’s wrong about inanimate objects.