June 9, 2013, by Stephen Mumford

Poetry or Prose

The distinction between poetry and prose has always puzzled me. I have to confess that I have never really ‘got’ poetry, though I want to remedy this. There are some obvious differences but I assume that they are thereby superficial. Poetry usually works within a form or structure. Sometimes this is regimented, as in the case of a sonnet, while at other times it is more free form. But poetry can be recognised instantly by its succession of short lines in contrast to prose that is mostly written in continuous paragraphs, some of them very long. I’m pretty sure the difference between poetry and prose is much deeper than that, however.

The fact that I struggle with poetry gives me a clue. As a philosopher, I like writing that is clear, precise and unambiguous and I must always strive for these ideals in my own work. When I write, I have an idea that I am aiming to impart to my reader and I do not want them to leave my text with an altogether different one. The poet typically does not have that aim. Each word will have been carefully chosen by the poet, perhaps where it is purposefully vague, resonant and no more than suggestive. The reader is encouraged to dwell on those words and mull them over for multiple meanings, using them as a device to conjure their own thoughts. Consequently, one is expected to spend much longer reading a poem, perhaps going back over it, line by line, and thinking of all the different things those words could signify. Poetry thus has a more pronounced subjective aspect. From the writer’s stance, the reader is enabled to develop their own.

This is a nice, neat theory of the distinction and perhaps it’s typical of an analytic philosopher to produce such a simple statement. The reality is almost certainly more complex and the boundary between poetry and prose far more vague. Some prose writers will similarly trade on ambiguities and leave the reader to contemplate a deeper meaning that is to be found. Consider Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, for instance, which is about more than a mere boat trip. And poetry might be used to convey an explicit message. Writers within both forms can have many different ways of conveying their meaning and different kinds of meanings to be conveyed. Poetry could then be no more than what Wittgenstein called a family resemblance concept, with no single feature in common to every instance but the sort of related resemblances between members that we find in biological families.

By way of illustration of some of the features of poetry, and the degrees by which they can appear in a single exemplar, I finish by offering the ending to Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach. How explicit or implicit is Arnold’s meaning here? How subjective or objective? Whatever those answers, I certainly find it touching, beautiful, and while it first raises my hopes, I do not blame Arnold at all for then immediately dashing them. There is a truth here.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

A very thoughtful post. I share your taste for ‘writing that is clear, precise and unambiguous’. If I read you correctly, you imply – rightly – that writing can’t be fully unambiguous: you say that you do not want your readers to get an ‘altogether’ different impression.

There’s some interesting thoughts on this matter from J.S. Mill, who criticised Bentham’s later writings for ‘perpetually aiming at impracticable precision. … He could not bear, for the sake of clearness and the reader’s ease, to say, as ordinary men are content to do, a little more than the truth in one sentence, and correct it in the next. The whole of the qualifying remarks which he intended to make, he insisted upon imbedding as parentheses in the very middle of the sentence itself.’ Eventually, ‘he could stop nowhere short of utter unreadableness, and after all attained no more accuracy than is compatible with opinions as imperfect and one-sided as those of any poet’ (essay on ‘Bentham’, 1838, revised 1859).

I agree with Mill that the later Bentham ‘spoke in an unknown tongue’, although I wish Mill himself had been a bit quicker to correct his own ambiguities in the next sentence (e.g. ‘one very simple principle’!). But as regards your post, I think Mill’s caution is important here: we can’t make our meanings perfectly clear, and must be content with a degree of ambiguity, otherwise our writing may become unreadable – or, fleshed out with a bevvy of qualifications, clarifications and distinctions, unreasonably long.

What about ‘prose poetry’?

I guess the distinction between a poet and an analytic philosopher does not lie on the ways they write/speak, but on what do they aim at by doing that, as you hint in paragraphs 3 and 4.

Roughly, poetry is evocation of meanings and a poem is a particular evocation of meanings. So the opposition is primarily between verse and prose (ways of writing/speaking with peculiar rhythms) rather than between poetry and prose. There are poems both in prose and verse, and I don’t see obstacles in analytic philosophy per se to be versified, except when there is a tension between clarity and rhythm, where the former is to be preferred in analytic philosophy. But the same tensions and choices are present in poetry: sometimes a particular evocation of meanings cannot be obviously achieved by verses, so it is better doing it through prose or other means.

Maybe it would be a good Twitter contest: versify your favorite philosophical argument/stance! #VersifyAnalyticPhilosophy

Very interesting post with ramifications in, among other subjects, the unfortunate split-off between analytic and continental philosophers.

I agree. I think the word ‘prose’ is generally used to mean ‘not poetry’ in the same way that ‘layperson’ means not professional or expert. So when we try to contrast poetry to prose we end up contrasting poetry with everything-else-all-lumped-in-together. So maybe a good way (for a philosopher) to ask the questions is: ‘What makes poetry POETRY??

i don’t really get poetry either, but it’s worth remembering that with the onset of modernism at the beginning of the twentieth century, poetry became much harder to understand. Before Ezra Pound and TS Eliot you’ve got a better chance. One can compare this with modernism in other art forms, such as painting; after Cubism, painting becomes more difficult to understand, and there is a need to educate your eye to appreciate it. However, it is easier to see how colours and shapes, divorced from any need to represent objects in a photographic way, can still be appreciated as pure colour and shape or as merely suggestive (e.g. Kandinsky or Miro). True, words can be appreciated for their sound alone to some extent, and there are examples of writers coining words for their sound alone (e.g. Lewis Carroll, Joyce), but once you separate a word from its meaning, it doesn’t amount to very much.

A poem like Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’ relies on historical and literary allusions to be understood, so I’m told. I have to take this on trust, as I can’t understand it at all. People I know and respect do understand and have told me that it is actually good. An excerpt:

The Chair she sat in, like a burnished throne,

Glowed on the marble, where the glass

Held up by standards wrought with fruited vines

From which a golden Cupidon peeped out

(Another hid his eyes behind his wing)

Doubled the flames of seven branched candelabra

Reflecting light upon the table as

The glitter of her jewels rose to meet it…

Sounds great. What’s he on about?

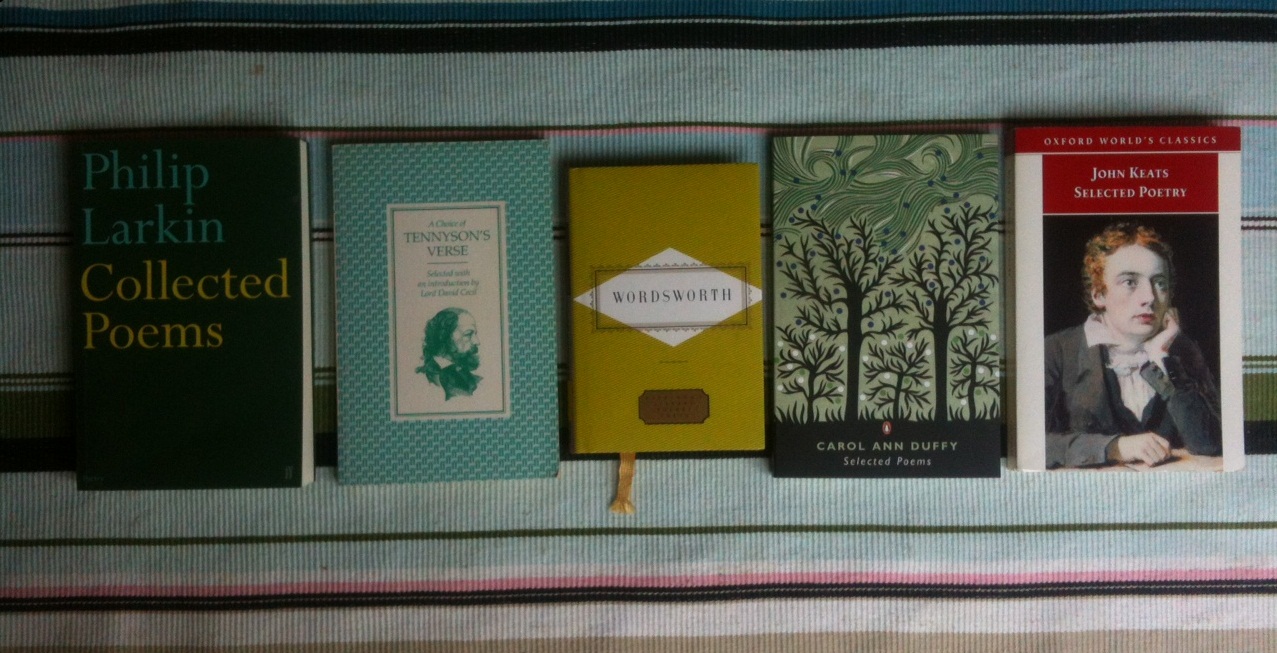

Phillip Larkin was contemptuous of the modernist direction in poetry and wrote poems that pretty much any literate person understands the first time around. Something like Water uses its clarity of language for persuasive effect:

If I were called in

To construct a religion

I should make use of water.

Going to church

Would entail a fording

To dry, different clothes;

My liturgy would employ

Images of sousing,

A furious devout drench,

And I should raise in the east

A glass of water

Where any-angled light

Would congregate endlessly.

Still, even Larkin rarely managed to go a whole poem without introducing a metaphor that needs to be pondered, exactly as Simon describes in his post. And perhaps that is where the key to poetry lies: choosing a word that carries with it other ideas – baggage that the writer and reader both share, which loads the phrase with more significance. Some of this baggage will be unconscious and therefore the poem’s power will be unexplained – making us feel that the poem is actually capturing the inexplicable. Perhaps it is.

Listening to something like Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood, you hear language being used to evoke scenes very vividly in a way that makes use of the meanings and associations that are latent in words (rather than stopping at their dictionary meanings). By describing a night as ‘starless and bible black’ he sets off all kinds of associations in the reader’s mind that bring to life that fathomlessness of a dark night and all the mystery within it. That would be impossible if you just tried to write clearly

Likewise, The Dead, Joyce’s final story in Dubliners, is written in plain English, nothing like the difficult stuff he went on to write, but the famous close of the tale is a good example of how a great writer can write poetically without needing a standard poetic structure and never letting go of literal meanings:

‘A few light taps upon the pane made him turn to the window. It had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight. The time had come for him to set out on his journey westward. Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.’

The repetition of the word ‘falling’ with the variation ‘faintly falling’ in the last instance is like a song, and of course all poetry started off as song, (not forgetting that Joyce was a keen singer too). And the way the words fall reminds us of the way snow falls – gentle yet relentless.