June 2, 2015, by Guest blog

Race and Rights: Black Soldiers Part 4

To mark the 150th anniversary of the ending of the American Civil War in 1865, James Brookes of the Centre for Research in Race and Rights analyses the visual culture of African American flags—regimental colours that expressed the black experience of war and of life in America itself. In the fourth and final blog of this four-part series, he looks at the 45th United States Colored Troops.

A Civil War regiment would typically carry two flags into battle, the national standard and the regimental colours. Amongst regiments of white Federal soldiers, the regimental colours were visual symbols of the state or home locality from which the men had volunteered. Regulations called for regimental colours to be dark blue, bearing the coat of arms of the U.S. and with a red scroll displaying the unit designation. However, the patriotic groups that made flags for departing volunteers complied with these regulations to differing degrees. Conversely, the United States Colored Troops, first formed in 1863, were not raised from such concentrated home communities as they were instead made up of less concentrated populations of free men of colour in Northern states, as well as runaway slaves and captured ‘contraband’ enslaved subjects.

USCT regiments were denied a level of affiliation to a particular state or community, unlike white volunteer regiments. The designation “United States Colored Troops” denies a level of affiliation to a particular state, and thus the regiments became representative of the entire African American population, whether free and enslaved. As a result, their regimental colours took on a visual symbolism that embodied various themes relating a full gamut of African American experiences in this period. These included the desire for full emancipation and equality, the attainment of citizenship, and, unsurprisingly, a lifelong, individual and collective determination to avenge the blood drawn from the slaveholder’s lash. Over 150 regiments of the USCT existed during the Civil War, composed of approximately 180,000 African Americans. The full spectrum of these unique banners of civil and militaristic self-representation holds much potential for interpreting the powerful ways in which black soldiers viewed their military service as a means to attain liberty, equality, and citizenship in the United States.

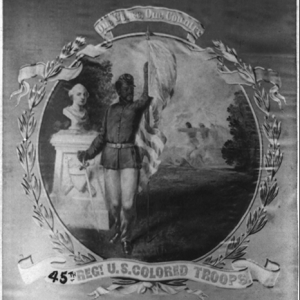

Image: David B. Bowser, “One Cause, One Country – 45th Regt. U.S. Colored Troops,” photographic print on carte de visite mount, Courtesy Library of Congress.

The 45th United States Colored Troops assembled at Camp William Penn, near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, during the summer of 1864. It was unique in that it was the only regiment in the war formed with a significant number of black soldiers accredited to the new state of West Virginia. The state historian Virgil Lewis ascertained that 212 black men enlisted in West Virginia. Those who recorded their profession upon their enlistment provide an insight into the composition of the regiment. Thirty five were farmers, another thirty five were labourers, seven were servants, and one was a barber. The rest did not designate a specific occupation. Other states which provided men to the 45th were Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Virginia.

Confederate General Jubal Early’s invasion of the north in July, 1864 triggered panic amongst the lower northern states as his Rebel army marched on Washington, D.C. Only four of the regiment’s ten companies were composed when they received orders to join a provisional brigade under the command of General Silas Casey to aid in manning the capital’s defences. Here this portion of the 45th would remain in garrison until March, 1865, participating in the second inauguration of President Lincoln and the only African-American unit to do so.

The remaining six companies continued to organise at Camp William Penn, and received their regimental colours on the 15 September, 1864. The Daily Evening Bulletin of Pennsylvania observed the ceremony, noting, “Aside from the little confusion arising from the inexperience of the troops, the evolutions were well performed.” Brigadier-General Birney addressed the regiment, “I have the honor to present to you this flag. It testifies [to the] confidence that you will bear it well and bring it back again with honor.” Birney stated that they had submitted to “the trials and fatigues incident to a soldier’s life; to undergo the toilsome march, the scorching suns of summer, and to bunk amid the snows and mud of winter.” By accepting the flag, the men had pledged to “incur the danger of long campaigning… to stand without shrinking when the shells are bursting over you, and when the balls whiz through your ranks.” Though the men of the 45th USCT were unmistakably untested at the time of their flag presentation, they were made abundantly aware of the expectations of military service.

The flag of the 45th USCT bears the illustration of an African-American colour sergeant holding the national flag in one hand and a sword in the other. The colour sergeant was chosen from amongst the best men in the regiment. His pristine appearance, well-postured stance, military deportment, and visionary gaze towards the flag identify the black soldier as an idealised warrior for the Union whilst simultaneously confronting the derogatory caricatures of African Americans in a nineteenth century United States imaginary. He stands before a bust of George Washington, the first president of the United States, as black troops charge forward into the storm of battle in the background. On the pillar atop which Washington’s bust sits is the seal of the nation. Wreathed in laurels, the image suggests victory is assured in the endeavour for Union and emancipation. Above the illustration of patriotic loyalty and steadfast duty to the principles and symbols of the young republican nation an inscription bears the words, “One Cause, One Country.” Though the imagery does not make an explicit recognition of anti-slavery, the phrase suggests the conflict as one in which loyal Americans, regardless of colour, could fight for the restoration of the Union.

The regiment remained at Camp William Penn until the 20th of September, when they began a long march to City Point, Virginia to join the X Corps. On their arrival, black war correspondent Thomas Chester observed that the 45th “looked as if it was made of good material.” The 45th were denied an opportunity to fight at New Market Heights in late September due to their lack of experience, but other USCT regiments fought gallantly and won 16 Medals of Honor during the engagement.

It was not long before they received their opportunity. Mid-October saw the 45th engage Confederate General Lee’s entrenched men along the Darbytown Road. The battle resulted in a Confederate victory but the 45th had shown their mettle. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton recommended one private, James M. Lyon of Company K, for a promotion to captain by brevet for his “bravery at the battle of Darbytown Road, Virginia and for gallant services during the war.” Those positioned in the highest levels of government recognised the contributions of African American soldiers, even when their efforts could not stymy defeat. The 45th participated in an attack on Rebel trenches at Fair Oaks, but suffered only one casualty before moving into winter quarters in front of Fort Harrison.

Though some were willing to acknowledge the fighting capabilities of black troops, discrimination was still prevalent. White soldiers murdered one private in the 45th USCT, shooting him twice as he collected firewood during the winter of 1864-5. African American men in the Federal Army occupied a tenuous position during the Civil War. Though provided the opportunity to fight for black emancipation and Union, they often found a continuous obstacle to their service in the entrenched and virulent prejudice of the white rank-and-file.

The spring of 1865 saw the two portions of the 45th united for the first time. The unit would be involved in several engagements in the closing weeks of the war, specifically participating in the fall of Petersburg. Though held in reserve at Appomattox, the 45th were present for Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865. The 45th then redeployed to Texas for the remainder of their service and conducted guard and provost duties. Tragically, clean water sources were difficult to come by on the Mexican border, and some of those who had survived the slaughter pens of Virginia succumbed to disease. Mustering out of service on November 4, 1865, the majority of the men rejected the opportunity to join a peacetime Regular Army black regiment as they instead chose to return to their homes to enjoy the peace and freedom for which they had battled.

James Brookes is an MRes student in the American and Canadian Studies department, where he is writing a dissertation on the visual culture of American Civil War soldiers. He begins his PhD in the department in September. He is a member of the postgraduate reading group at the Centre for Research in Race and Rights.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply