May 11, 2015, by Guest blog

Race and Rights: Black Soldiers Part 1

To mark the 150th anniversary of the ending of the American Civil War in 1865, James Brookes of the Centre for Research in Race and Rights analyses the visual culture of African American flags—regimental colours that expressed the black experience of war and of life in America itself. In the first of this four-part series, he looks at the 3rd United States Colored Troops.

A Civil War regiment would typically carry two flags into battle, the national standard and the regimental colours. Amongst regiments of white Federal soldiers, the regimental colours were visual symbols of the state or home locality from which the men had volunteered. Regulations called for regimental colours to be dark blue, bearing the coat of arms of the U.S. and with a red scroll displaying the unit designation. However, the patriotic groups that made flags for departing volunteers complied with these regulations to differing degrees. Conversely, the United States Colored Troops, first formed in 1863, were not raised from such concentrated home communities as they were instead made up of less concentrated populations of free men of colour in Northern states, as well as runaway slaves and captured ‘contraband’ enslaved subjects.

USCT regiments were denied a level of affiliation to a particular state or community, unlike white volunteer regiments. The designation “United States Colored Troops” denies a level of affiliation to a particular state, and thus the regiments became representative of the entire African American population, whether free and enslaved. As a result, their regimental colours took on a visual symbolism that embodied various themes relating a full gamut of African American experiences in this period. These included the desire for full emancipation and equality, the attainment of citizenship, and, unsurprisingly, a lifelong, individual and collective determination to avenge the blood drawn from the slaveholder’s lash. Over 150 regiments of the USCT existed during the Civil War, composed of approximately 180,000 African Americans. The full spectrum of these unique banners of civil and militaristic self-representation holds much potential for interpreting the powerful ways in which black soldiers viewed their military service as a means to attain liberty, equality, and citizenship in the United States.

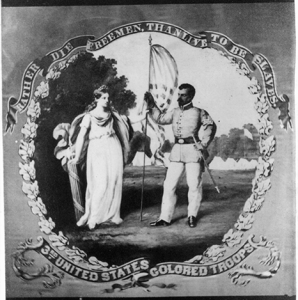

Image: David B. Bowser, “Rather die freemen, than live to be slaves – 3rd United States Colored Troops,” photographic print on carte-de-visite, 1860-70, Courtesy Library of Congress

Camp William Penn, established in June, 1863, was the only camp-of-instruction set up exclusively for black soldiers during the Civil War. The camp sat outside of the limits of Philadelphia, a city notable for the bitterly entrenched prejudice held by whites towards African Americans. Louis Wagner, the commander of the camp, supported the black soldiers under his command. He paraded his regiments down Philadelphia’s main thoroughfare and instructed his men to ignore segregationist policies on the local trains. Nearly 11,000 men from the United States Colored Troops passed through the camp. One of the first regiments trained there was the 3rd United States Colored Troops.

The 3rd United States Colored Troops was composed of men from Pennsylvania and would depart from Camp William Penn August, 1863. The men who made up the regiment came from a variety of civilian backgrounds. Isaac Becket, born in the state in 1842, had worked as a waiter in Philadelphia. Moses Dunmore was born to an extensive family of free blacks in Maryland around 1843 and had moved to Pennsylvania to work as a farmer prior to his enlistment. Other occupations included labourers, wagon teamsters, boatmen, and barbers.

The 3rd received a “large and handsome American flag” and local civilians turned out for the ceremony. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, a “special train left the depot… consisting of fourteen cars, well loaded with colored persons, and among them a sprinkling of white ladies and gentlemen, all bent on witnessing the ceremony.” A band composed of coloured musicians escorted the excursion party. The 3rd formed for a series of field manoeuvres which it executed with “commendable promptness” before an audience of around 1,500 spectators comprising “all colors, ages and sexes.” The regiment was positioned in a hollow square around a flagpole and, as the standard rose, the musicians struck up the Star Spangled Banner.

The abolitionist George H. Earle gave an emphatic speech. He noted that the troops had drilled on consecrated ground that had “witnessed a struggle during the revolutionary war.” In the Civil War, Unionists asserted that they were preserving the republican government founded by their revolutionary forefathers. Earle stated that “the inspiration of the present moment” was divine. The event emphasised that, “America is calling into her service all her servants, for the purpose of protecting her nationality, regardless of color.” He then addressed the discipline and fighting capabilities of black soldiers.

Regardless of the fact the 3rd were yet to fight Earle was confident of their abilities, utilising the successes of other black regiments at Milliken’s Bend, Morris Island, and Baton Rouge in order to assuage any doubts about the 3rd. Other black regiments had “reflected honor” on this newly formed unit, asserting that they should be able to fight as capably as those who had set the precedent of honourable service. The statement contains the expectation that all black units would conduct themselves properly, but also a warning that should the 3rd falter they might reflect disgrace on other black regiments. Here, the implication is clear. Earle emphasises the collective perception of African American combat service in the war: what occurred on the regimental level could have significant repercussions for the entirety of the United States Colored Troops, and for the black population more generally. According to a white supremacist schema at best and a white racist lens at worst, Black soldiers bore the responsibility of proving themselves as soldiers, and by logical extension, citizens too.

The 3rd also bore a regimental standard of colours designed by the abolitionist artist David B. Bowser. The flag depicts a black sergeant in a pristine dress uniform receiving a national flag given by Columbia, the white, female personification of the United States. The image bears the inscription “Rather Die Freemen, Than Live To Be Slaves”, making the flag a powerful statement about the black troops’ motivation to fight. The maxim is reminiscent of Patrick Henry’s revolutionary declaration, “Give me Liberty, or give me Death!,” a rallying cry bleeding through the ungirding ethos of all Black radical movements during this period. Although the majority of men that composed the regiment were free blacks, their motto aligns them with all African Americans, free or enslaved. The regiment is fighting for the collective enhancement of their race’s position in the United States. The image on the flag is unique as it contains an illustration of a white woman presenting the symbolic representation of the nation to an armed African American with a martial appearance. The stalwart black soldier bears responsibility for two precious symbols of the nation, giving viewers an indication of the mettle of the men forming the 3rd and how they viewed themselves as agents preserving the Union and ensuring black liberation.

On August 16, 1863 the Philadelphia Inquirer reported that the 3rd had made a splendid impression since their arrival on Morris Island, South Carolina by observing, “they make excellent soldiers.” The 3rd took positions in the trenches before Fort Wagner, a place made famous by the black 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry’s failed but gallant assault on the fortifications. The Inquirer updated its readers on the progress of the 3rd in February, 1864, the paper announced that they had been “under fire, doing duty in the trenches in front of Fort Wagner for months, and the greatest confidence is felt by their friends that these regiments will sustain their former good reputation.” The drawn-out trench warfare at Fort Wagner was brutal for the 3rd.

The 3rd redeployed to Florida following their engagement on Morris Island. Here they regularly conducted raids on nearby plantations, where their objectives were often to bring in enslaved women, men, and children and to destroy Confederate property. On one such expedition, a detail proceeded sixty miles up the St. Johns River for the purpose of a raid. They rowed by night and hid in the swamps by day, marching thirty miles into the interior before gathering up “fifty or sixty [enslaved peoples], besides several horses and wagons, burned store-houses and a distillery belonging to the rebel government, and returned bringing their recruits and spoils all safely into camp.” On their return they fended off a body of cavalry. For their “courage and good conduct” the all-black expedition party was “commended in an order by the General commanding the Department of the South.”

The 3rd remained in Florida until they mustered out of service on October 30th. During their service, the regiment never lost a man as prisoner. The general feeling amongst the enlisted men was that “immediate death was preferable to the treatment likely to be experienced as prisoners.” On “one occasion, a soldier who had been surrounded and driven into a river, stubbornly refused repeated calls to surrender, and was killed on the spot.” Confederates perceived black troops as insurrectionist enslaved freedom fighters, to be executed or “resold” into slavery, and their white officers faced death as instigators of slave rebellion. The motto inscribed on their regimental flag “Rather Die Freemen, Than Live To Be Slaves”, though it may appear hyperbolic to a 21st century audience, became a perilous reality for the men of the 3rd.

James Brookes is an MRes student in the American and Canadian Studies department, where he is writing a dissertation on the visual culture of American Civil War soldiers. He begins his PhD in the department in September. He is a member of the postgraduate reading group at the Centre for Research in Race and Rights.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply