December 19, 2014, by Guest blog

Race and Rights: Ferguson Part 5

Post by Patrick Henderson

Below is the fifth of a multi-part series responding to events in Ferguson – the protests and civil disorder that began the day after the fatal shooting of an African American man, Michael Brown, by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, on August 9, 2014, and continued after the decision on November 24, 2014 by a grand jury not to indict the police officer. Nottingham’s Race and Rights cluster and postgraduate reading group, based in the Department of American and Canadian Studies, examine Ferguson through the lens of their research. In this fifth posting in the series, Patrick Henderson looks at Ferguson in the context of techno and police violence of the 1990s.

Techno. Perhaps a musical movement not readily associated with social activism by the vast majority of us. Though more commonly synonymous with repetitive bass and recreational drug use, my research into the Detroit-based group Underground Resistance has revealed a great deal more depth to a genre that is quite easy to greet with derision, at least in scholarly fields. Formed in 1989, as part of the so-called ‘second wave’ of Techno in the Motor City, Underground Resistance brought together Jeff Mills and ‘Mad’ Mike Banks in a conscious bid to politicise the predominantly ‘rave’-orientated sound of the burgeoning Techno scene. Moving past allusions to the post-human future popular amongst the scene’s originators, wherein race, gender, sexuality and all other markers of ‘difference’ were no longer an issue, Mills and Banks brought the focus back to a flagging African American community, struggling to function within a deindustrialised and apparently hopeless Detroit. Crippled by the departure of the motor trade on which many residents were reliant on, the city had spiralled into a seemingly perpetual decline, blighted by crime, unemployment and general poverty. Underground Resistance questioned how we could embrace the concept of a post-human world, when it was largely African Americans who had been left to suffer in what the FBI had revealed to be the “most dangerous city in America”.

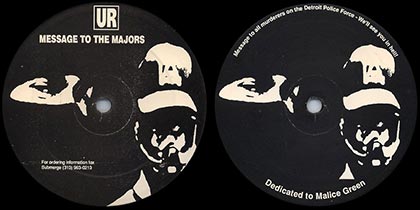

“Message to all murderers on the Detroit Police Force – We’ll see you in all in hell!”, reads the liner note on the label of UR-023, Message To The Majors, a 12” single released by the group in 1992 and “dedicated to Malice Green”. In the wake of the highly publicised beating of Rodney King in Los Angeles earlier that year, leading to the infamous L.A. riots, the case of Green has been somewhat less documented. Struck approximately 14 times in the head with the flashlight of Detroit police officer Larry Nevers, joined by fellow officer Walter Budzin, the unarmed Green died of respiratory failure following a struggle purportedly initiated when he failed to relinquish a vial of crack cocaine. Subsequent trials saw both officers charged with second degree murder, with colleagues Robert Lessnau and Freddie Douglas acquitted of their involvement in the incident. Whilst some justice, if it can be called that, was served following the murder of Green, this trope of police brutality enacted upon unarmed African American men and women throughout the U.S. has become upsettingly familiar.

Indeed, the trend shows little sign of abating, with the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson coming over 20 years since Underground Resistance issued their message to the Detroit Police Force. The location may be different, but the situation remains the same. Robin D. G. Kelley’s piece summarising the similar cases that occurred over the duration of the Ferguson court proceedings makes for particularly chilling reading. Brown is just another name, along with Green’s, in “a stack of dead bodies that rises every time we blink”. The sheer volume of the dead leads to a dehumanisation of the victims as we “hold their names like recurring nightmares, accumulating [them] like ghoulish baseball cards”. With the apparent stasis in relations between law enforcers and African Americans showing no sign of changing, the demonstrations in Ferguson are the culmination of the consistent denial of justice and equality to a group of people who are tired of waiting.

Underground Resistance certainly seem to favour the course of direct action to enact change within society. Their 1991 Riot EP(UR-010) came a year before the L.A. Riots, pre-empting the violence with samples of the roars of an angry crowd set against pounding percussion to create a soundtrack for the ensuing uprising. A video for the track produced by the group a full two decades later placed the events in L.A. within a global narrative of uprising, from the violence in Detroit, 1967, to “The Battle for Tahrir Square” in Egypt, 2011. Rather than constituting isolated responses to local issues, Underground Resistance present this struggle for justice as universal and ongoing. On November 24, 2014, a grand jury revealed its decision not to indict Darren Wilson. Underground Resistance chose to post the video without comment, almost certainly in response to the decision. Whilst posted in solidarity, the continued relevance of a track and video chronicling decades of unrest and inequality towards African Americans can’t fail to be disheartening. Little has seems to have changed. Progress, if any, is proving to be glacial.

Patrick Henderson is an MA student in the American and Canadian Studies department, where he is writing a dissertation on Detroit techno and black protest. He is a member of the Race and Rights research cluster and PG reading group.

Photo: Underground Resistance single “Message To The Majors” (1992)

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply